A lion and a legend: Remembering Jpost's Ari Rath

Ari Rath, former editor-in-chief of The Jerusalem Post, treated members of the Post staff as family.

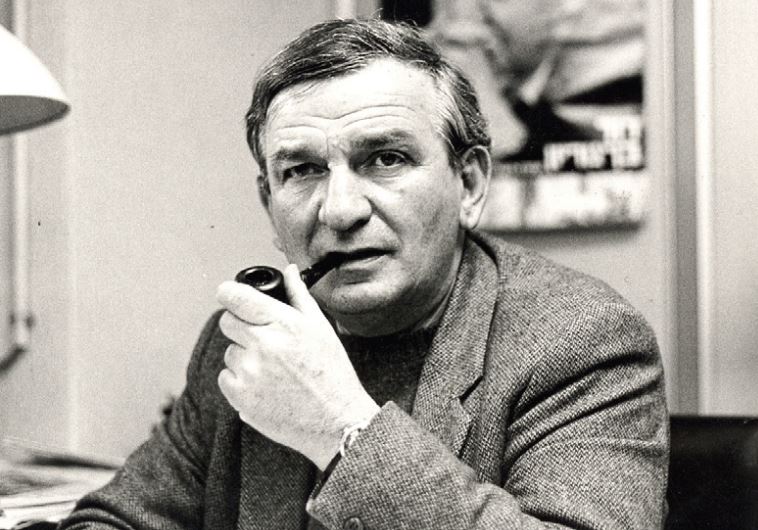

The now-91-year-old Ari Rath in 1989, during his days as ‘Jerusalem Post’ editor-in-chief(photo credit: DAVID BRAUNER)Updated:

The now-91-year-old Ari Rath in 1989, during his days as ‘Jerusalem Post’ editor-in-chief(photo credit: DAVID BRAUNER)Updated: