Charlotte Salomon, a young German-Jewish artist who was murdered in the Holocaust, had a talent that was way ahead of her time and the new animated documentary, Charlotte, which is playing in theaters and VOD platforms around the US, pays homage to her life.

There is much to enjoy in this moving and absorbing film, which was made by Tahir Rana and Eric Warin, although it is a fairly conventional animated biopic about the short, tragic life of a woman who was a visionary, perhaps even a genius and the intensity of her gift comes through only in flashes. However, it is a well-made, affectionate look at her and it will certainly help keep alive her talent and her voice, which the Nazis tried to silence forever.

This movie is in English, with Keira Knightley voicing Charlotte and a host of other acclaimed actors, including Jim Broadbent and Brenda Blethyn as her grandparents, Sophie Okonedo as a benefactor who aids her and Mark Strong as her lover.

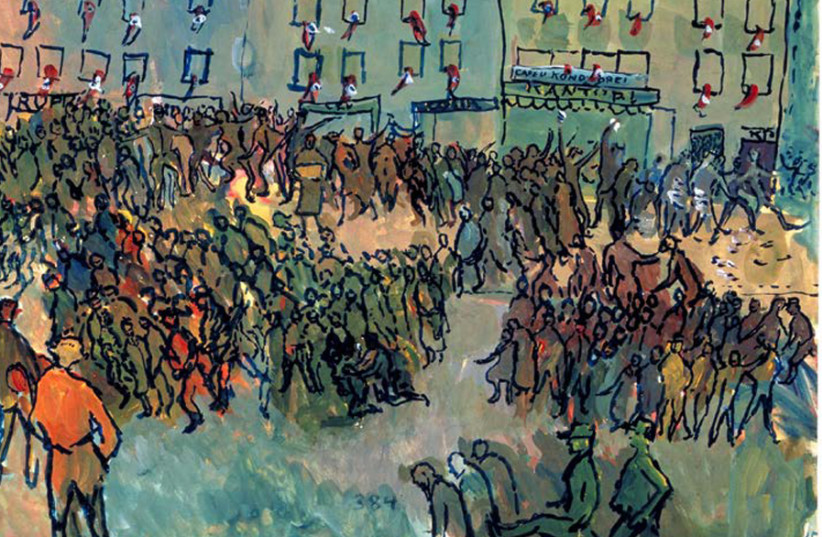

Salomon is known today for a collection of over 750 paintings that tell the story of her life, called, Life? or Theater?, which contains text and songs and are considered an important precursor to today’s graphic novels. She was born in Berlin in 1917 and escaped to the south of France in the late ‘30s. She was able to give her masterwork to a friend who preserved it until the end of the war.

She was a gifted artist and this helped her cope with a deeply troubled life. Her mother committed suicide when Salomon was a child, although she was not told the truth about how her mother died. Her grandfather – an imposing and, by her account, cruel man – told her about the suicide later, as well as that many other of her relatives had also taken their own lives. Many of her biographers believed he sexually abused her but, due to the circumstances of their life in the Nazi era; she was forced to stay in contact with him.

In 1936, in spite of all the anti-Jewish decrees, she was accepted to a prestigious art academy, a testament to her outstanding talent and had a love affair with Alfred Wolfsohn, her stepmother’s singing teacher, who encouraged her artistic development. But her father was arrested and briefly imprisoned and – following Kristallnacht – it became clear that the family could not remain in Germany.

Charlotte relocated to the south of France, where she blossomed for a time but then was pressured to care for her grandfather. She took revenge on him in a shocking way that perhaps should have been given more emphasis in the film. Eventually, she met and married Alexander Nagler, another refugee and she was pregnant when, at 26, she was sent to Auschwitz and killed.

Although her artistic interests were very different from Anne Frank’s, who was entranced by American cinema, and their wartime experiences were very different, there is some similarity between the two. Not coincidentally, Anne Frank is also the heroine of a recent animated film, Ari Folman’s docu-drama, Where is Anne Frank, which opens in Israel next week. For many reasons, the animated format is particularly evocative when telling these wartime stories, and both of these films portray heroines who are willful, sometimes mischievous and passionate about their love for life in the face of intense persecution and evil.

The visual style of Charlotte is obviously inspired by Salomon’s creations, but it does not convey their unique beauty. While her paintings are on screen at times, they are not front and center as much as I would have liked. Much of the dialogue is taken from her own writing and her words convey her strength of character and her torment.

In the film, her character says, “Only by doing something mad can I hope to stay sane. I’m going to paint the story of my life and I don’t know how much time I have left... I’ll put everything I have into it, everything beautiful and everything hideous.” I hope that many viewers will be inspired to seek out her works, which have been exhibited around the world including at Yad Vashem and are available in book form.