Guillaume Levy-Lambert sees one of his life roles as a conceptual artist, a performer who shares stories of divine providence. He sends a message of happiness and encouragement to people in his audiences who might have profound stories of divine providence in art that they might have been too bashful to share.

Guillaume, who turned 60 on May 21, is using his birthday to encourage the people he calls his “cosmic siblings” to talk about miracles of connection in their lives. He has placed Facebook ads and even created a website called 21may1962.com to find people the world over who share his exact birth date. By his calculations, close to 300,000 people were born the same day.

And his strategy is working. These birthday mates, his cosmic siblings, are contacting him from far-flung corners of the world – from the US, the United Arab Emirates, the Philippines, to Africa.

Guillaume brings a formidable background to this project. He is the co-founder with his partner, Mark Goh, of the globe-trotting MaGMA Asian Art Collection. With Sean Soh, he has created Art Porters, one of the top galleries in Singapore to advocate for emerging artists from Southeast Asia.

He climbed the corporate ladder in the 1980s and ’90s as an investment banker with BNP Paribas Asset Management. He then made a radical shift to the advertising and communications industry, becoming Asia Pacific regional chairman for Publicis after building up their Asian market from scratch.

“It took years for me to leave the corporate world and start a conscious process of becoming both an art dealer and conceptual artist,” Guillaume said in a recent interview at Haifa’s Dan Carmel hotel during a recent visit to the country.

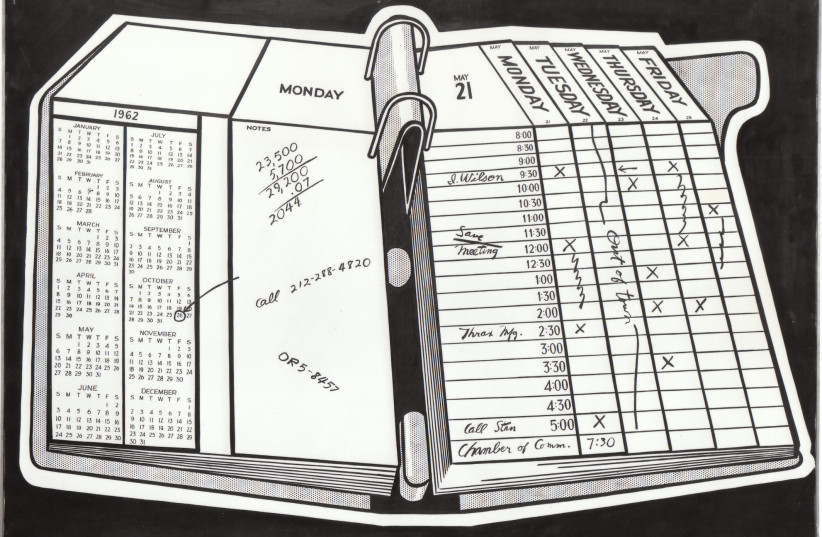

Among the sharing of inspirational stories and projects from members’ lives, Paris-born and raised Guillaume focused his presentation around iconic American pop artist Roy Lichtenstein’s Desk Calendar, a painting with deeply personal meaning, of divine providence, synchronicity, and a fair share of identity crisis.

“An experience I love is appropriation – taking something for one’s use. When I see a work of art on the Internet, in a museum, in a gallery, or in a friend’s home, I wonder what it’s saying to me. Everyone can play this game and uncover infinite layers of meaning.”

Guillaume had become aware of the power of his birth date in August 1999, soon after meeting his future life partner, Mark Goh, in Singapore, where he has lived the life of an expatriate for more than two decades. They took their first trip together to California soon after meeting.

Upon entering a gallery at the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art, MOCA, where Roy Lichtenstein’s Desk Calendar filled a wall, what jumped out immediately was a plain 1960s-style office desk calendar with his birthday, May 21, written large on the right side of the page. On the left side, Lichtenstein uncannily included Guillaume’s year of birth, 1962, and a single date circled on a 12-month planner. For emphasis, an arrow pointed to October 26, which happened to be Goh’s birthday.

“Seeing my exact date of birth as the focus of the Calendar painting was surprising enough. Then seeing October 26 felt extremely lucky – like we’d just won a big lottery.”

Guillaume Levy-Lambert

“Seeing my exact date of birth as the focus of the Calendar painting was surprising enough. Then seeing October 26 felt extremely lucky – like we’d just won a big lottery,” Guillaume recalled, as he tried to make sense of the message for him in this painting by Lichtenstein, his favorite artist since childhood.

“I did think at the time that it was a good omen, which is about as close as I could get then to speaking about divine providence. If you asked me if I believed in God, I would have said, ‘I don’t know.’”

Confronting indifference

THE ENCOUNTER with Desk Calendar prompted Guillaume to confront his relative indifference toward his Jewish faith and to answer some questions. He turned to Rabbi Mordechai Abergel, the chief rabbi of the Orthodox Jewish community in Singapore.

“For many years, my rational mind kept questioning what happened at the museum in Los Angeles,” Guillaume recalled.

“With a mix of reluctance and excitement, I came to see Desk Calendar as a black-on-white mathematical proof of the existence of God, as important as Einstein’s blackboard demonstrating the theory of relativity. The painting led me to a path of acknowledging God, including a bar mitzvah on my 39th birthday – 26 years late.”

Guillaume chose to have his bar mitzvah just outside Paris, in the same synagogue and with the same rabbi he had refused his parents as a nearly 13-year-old boy. His parents invited everyone who should have been there in 1975, including Guillaume’s paternal grandmother.

“I look back at my young self and my resistance to observing Judaism, and I can imagine God taking matters into His own hands, saying: ‘Okay, young Guillaume. You don’t believe in My existence. How about I make you gay, and that way you will understand what it means to be Jewish?’” he quipped.

“There’s a sameness, with a somewhat hidden difference. When you grew up as gay, at least in the 1970s, you felt like you were the only gay in the village. That’s pre-Internet. There were no support groups or role models – similar to my experience of being Jewish in an assimilated environment.

“What I know is that discovering God a few months after first seeing the painting, at age 37, and the rich adventures that followed, are a privilege, what some people call God’s grace.”

“What I know is that discovering God a few months after first seeing the painting, at age 37, and the rich adventures that followed, are a privilege, what some people call God’s grace.”

Guillaume Levy-Lambert

Guillaume calculated the probabilities of a couple approaching this painting and finding both the date of birth of one and the birthday of the other on it. “I was trying to reassure myself that what had happened was extraordinary, but not more so than winning a big prize at a lottery,” he said.

“I was hoping that I hadn’t stumbled upon something more than that. I wasn’t consciously ready to change my assumptions about God’s role in the world. But I did ask myself, is this how the burning bush felt for Moses?”

Roy Lichtenstein

ROY LICHTENSTEIN was born on October 27, 1923 in New York’s Upper West Side to a wealthy German Jewish family. He spent World War II in Europe on duty as a part of the infantry, where he made sketches. Lichtenstein got his big break as an artist in the early 1960s, when gallery owner Leo Castelli signed him to his prestigious stable of artists. Guillaume met briefly with Lichtenstein’s widow Dorothy; the artist had died a few years earlier in 1997.

Besides the dates on the painting, there are phone numbers, a mysterious calculation, and a few names, which Guillaume has worked on decoding, teasing out hypotheses about what the dates, numbers and names meant to Lichtenstein.

“Of course, I asked myself, what am I supposed to do with my own calendar story? Desk Calendar is the most autobiographical of Lichtenstein’s pop-art era paintings of the 1960s,” Guillaume explained, while pointing to a jpeg where he stands in front of Desk Calendar, dressed in a white shirt decorated, symbolically and harmoniously, with the Lichtenstein dots he is striving to connect.

“Like me, many were curious to know if the phone number on the painting was a working number. When people called, I got them to leave a voice mail. Some thought they were actually speaking to Roy Lichtenstein,” Guillaume recalled with amusement. He would be thrilled when a caller would announce that he or she too shared the painting’s same date of birth.

“There is beauty in everything, and what I call ‘divine embroidery’ connecting everyone. It’s up to us to reveal it, notice it, and celebrate it,” Guillaume said.

Guillaume shared his latest findings in a free Zoom talk on May 21, going beyond what he discussed in a 2017 TedX talk on “Divine Providence,” delivered in Washington, DC; and in Evidence, a short documentary created with Romy Engel.

Evidence, featuring chats with people who viewed Desk Calendar when the painting traveled to museums between 2011 and 2016, was exhibited at the Contemporary Jewish Museum in San Francisco not long before the pandemic. ■

Guillaume Levy-Lambert welcomes readers to write to him or videotape stories that connect birthdays and yahrzeits to art and divine providence. He can be reached via linktr.ee/GuillaumeLevyLambert.

The writer wrote the first article about Guillaume Levy-Lambert’s art-collecting activities in 1988 for The Japan Times, when they were both in their mid-twenties. It was by divine providence that Guillaume Levy-Lambert saw her Facebook post announcing her move to Haifa, just as he was checking into the Dan Carmel Hotel in the city, a short walk from her new home.

Guillaume, by divine providence, also plays a walk-on role in the writer’s memoir, The Wagamama Bride: A Jewish Family Saga Made in Japan.