Leonard Cohen is up there with the icons of rock-pop-folk history. But, had the feted Jewish-Canadian troubadour not made the surprising, and seemingly quixotic, decision to pop over here in the fall of 1973, the world of commercial Western music may have looked very different today.

That may sound like the stuff of media-fueled hyperbole but, half a century ago, Cohen came to Israel from his hideaway abode on the Greek island of Hydra when he was in the deepest doldrums, in terms of both his life and his art.

“He was at a dead end. He was unhappy in his marriage, actually not exactly a marriage, his relationship [with Suzanne Elrod, over a decade his junior, with whom he had two children]. He’d talked about retiring,” says Matti Friedman, a Canadian-born Jerusalemite author and journalist whose oeuvre includes Who By Fire: Leonard Cohen in the Sinai.

Leonard Cohen's wartime visit to Israel and the IDF

The tome came out last year, in English and Hebrew, and shines a well-researched insightful light on Cohen’s momentous visit to Israel and his subsequent month-long circuit of IDF outposts and bases as the Yom Kippur War raged around him.

There are all sorts of tales and takes that have been doing the rounds of musical circles, and found their way into “received opinion” over the years, about why a star of the global music industry suddenly surfaced at the eastern end of the Mediterranean Sea.

“He kind of escaped from the island and tried to shake himself out of his situation,” Friedman suggests. The 40-something writer believes that Cohen’s jaunt here may have also been due to a need for a spiritual anchor as he sought a way out of his inner turmoil.

“Part of the visit is motivated by his desire to be with the Jewish people at a moment of crisis. Part of it is his personal crisis and his professional crisis.”

Anyone who has listened to Cohen’s music, and delved into his highly emotive and evocative crafted lyrics, can probably go along with the idea that those two areas of Cohen’s life were one and the same.

Friedman feels that the late singer-songwriter-poet’s pathway, 50 years ago, lead directly to his appearance among the military maelstrom of those fateful days in 1973, when Israel was rudely awoken from its post-Six Day War euphoria and faced existential challenges of the most palpable nature.

“It all kind of converges on the Sinai,” says Friedman.

Mind you, it wasn’t entirely a matter of serendipity. Cohen did get some help from Oshik Levi. In 1973 Levi was already an established member of the local showbiz scene, having recorded the soundtrack of Ephraim Kishon’s award-winning comedy-drama The Policeman, and treading the boards across the country with The Twins trio.

“Yes, I suppose you could say I’m ‘guilty’ of getting Cohen to join in with us,” says the 79-year-old singer.

He had also been following Cohen’s burgeoning career. “I’d been listening to his records for a few years,” Levi notes.

He encountered the Canadian star on the second day of the Yom Kippur War. Cohen had already put in several entertainment stints at the Hatzor Air Force base near Ashdod, the day before.

“I was on my regular café round,” Levi recalls.

“I’d been to Abie Natan’s California [on Dizengoff Street] and went onto Pinati [on the corner of Dizengoff and Frishman]. When I got there I saw Leonard Cohen sitting with Ori Levy, who was an actor with the Cameri Theater at the time. I wondered what he was doing here.”

He was also not about to miss out on the opportunity to say hello to a true musical VIP, at Pinati.

“I went over to him and asked him what he was doing in Israel. He said I heard you were in trouble. I thought of volunteering on some kibbutz.”

That sounds like a creditable altruistic reason for crossing the Aegean Sea, but Levi says there was an ulterior motive behind Cohen’s Middle Eastern foray. While Friedman sees Cohen’s visit here as the result of an emotional-professional impasse, Levi has a very different, much earthier, view of things.

“He had a lover here called Rachel. A beautiful Yemenite woman with green eyes.” Cohen’s dalliances are the stuff of legend, so perhaps passion had some say in his whereabouts in October 1973.

Be that as it may, Cohen’s personal and creative trajectories were about to take a sharp turn. Levi helped dissuade the unsettled star from plowing fields or milking cows to do his bit for the country in its hour of need: “I told him to forget about the kibbutz. You’re coming with us, to play music,” Levi recalls. The first person plural referred to Levi and his merry musical band of Mati Caspi, Mordechai “Pupik” Arnon and Ilana Rovina.

“I managed to convince him, and I called the others and we drove over to Hatzor.”

The scene was set for the battle-weary troops to meet the Jewish star.

“I got on the stage [at the airbase cinema building] and sang my songs, and then I told the audience I had a great surprise for them and I introduced Leonard Cohen,” says Levi. That must have been quite a moment.

“The soldiers went wild.”

ALTHOUGH PERHAPS not all the soldiers knew who he was – and some might not have had good enough English to understand what he was singing about – Cohen had already made his mark here, the previous year, at a particularly eventful concert at the ICC in Jerusalem.

During the concert, he felt that he was not “in the zone” and was not giving the ticketholders their money’s worth. He addressed the audience and told them in plain terms that he was not doing himself or them justice. He said he was stopping the show and the audience members would get a refund. In the end, he returned to the stage and completed the gig for a wildly enthused crowd. Clearly, Cohen was not exactly an unknown here.

“I asked Mati to join him on stage [at Hatzor],” says Levi. “Cohen knew about three or four chords on the guitar, and Mati was a much better instrumentalist. He really wowed Leonard.” Cohen had a similar effect on his khaki-clad audience. “The base commander asked us to do another show later,” Levi notes.

It soon became clear that, if Cohen had come to Israel to regain his spiritual-emotional equilibrium and rekindle the creative spark, he had hit the nail on the head with a resounding, lyrical, life-affirming knock. The muses got that too.

“Between the two shows he sat down, with his guitar, and wrote “Lover Lover Lover,” says Levi referencing the number which eventually found its way onto the New Skin for the Old Ceremony album that Cohen put out less than a year later.

It seems that Cohen had managed to shake himself out of his ennui and despondency. That is probably precisely what he was hoping to experience when he hopped on a plane from Greece, but probably could not envisage it as a coherent decipherable image. The second show of the day, at the air force base, featured the brand new song and it duly met with a rapturous response.

The IDF soldiers packed up their firearms, ammo, and other kit and got back to the war – which was not going at all well at that point – while the musicians prepared to make their own tracks in the direction of the frontlines.

“We drove to the Sinai and spent close to a month there,” says Levi. They had their work cut out for them. There were plenty of Israeli soldiers in need of a pick-me-up between offensive and defensive action, and seeing their friends killed.

“We performed 6-8 times a day. We went all over the place, like Port Said [near the northern end extremity of the Suez Canal] and other places. We’d sleep rough.”

BY THAT stage Cohen was feeling somewhat rejuvenated and less desperate. In his unpublished manuscript The Final Revision of My Life in Art, he wrote: “…because it is so horrible between us I will go and stop Egypt’s bullet. Trumpets and a curtain of razor blades.” The “us” referred to his waning relationship with Suzanne Elrod.

Cohen found himself traipsing across the desert expanses of the Sinai, often dodging mortar fire, even venturing into mainland Egypt. Troubled as he was, Cohen was not looking to paper over his emotional cracks with some bling-bling façade. He was under no illusions of grandeur regarding his contribution to Israel’s fight for survival, and he was not looking to hog the spotlight.

Friedman says that did the trick here.

“Had he come in with an entourage, photographers, and this kind of pose, it would have never have worked. The reason why it worked is that he was clearly not exploiting. He came by himself. There’s no footage of any of the concerts, no groupies. He is very authentic. He is sitting on the sand. That’s it. Otherwise, the soldiers would have picked up on that – that this guy was using them in some way, that it was a PR stunt.”

That was remarkable, and an indication of Cohen’s sincerity, and the genuineness of his quest for meaning and self-worth. Just the year before, he had played for sell-out crowds at major venues across Europe, including London’s Royal Albert Hall, the Konzerthaus in Vienna, and the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam, ending the tour with the dramatic show in Jerusalem.

That’s all a far cry from performing haunting ballads slap bang in the middle of a war zone in the Middle East.

It wasn’t just about playing music and singing his painstakingly crafted lyrics which, later in life, he said he “sweated blood” to produce.

Levi, for example, records witnessing “horrendous scenes” as bloodstained corpses and seriously wounded IDF soldiers were loaded into trucks and helicopters, with Cohen sometimes helping out with the stretchers. That just had to leave a deep enduring impression on any artist, particularly a songsmith of Cohen’s anguished ilk.

It also brought him back home to his own Jewishness which, he noted in a 1985 television interview with Dan Margalit, he never really abandoned.

“I write out of my own tradition,” said Cohen, when the interviewer asked him how Jewish his songs were.

“My heart was circumcised in the Jewish tradition,” Cohen added with characteristic dark humor.

HE MAY have hung onto the umbilical cord of the faith into which he was born and raised but, typically, he continued to wrestle with his identity issues and dig into troubling personal seams. That resonates powerfully in “Lover Lover Lover,” the song that emerged as Cohen’s creative juices began, once more, to flow as he came face to face with reality in its most brutal form. The first stanza opens with: “I asked my father, I said, ‘Father change my name.’ The one I’m using now it’s covered up with fear and filth and cowardice and shame.” That doesn’t particularly sound like something you write when you are at peace with yourself and happy with your place in the world.

Cohen’s dichotomous, or multi-pronged, take on life seems to be a leitmotif of his time on terra firma. While his time here, getting down and dirty – and close to the sharp end of corporeal life – in the middle of the Yom Kippur War, reinforced his connection with his Jewish roots, he remained a humanist. For him, life was sacred regardless of your religious allegiances.

“Lover Lover Lover” closes with a fervent wish for the safety and wellbeing of all mankind: “And may the spirit of this song. May it rise up pure and free. May it be a shield for you. A shield against the enemy.”

“At the time, Cohen first said the song was dedicated to the Israeli troops, and then he talked about the Egyptian soldiers,” notes preeminent rock and pop expert and veteran broadcaster Yoav Kutner.

“When he came back here in 1980 he explicitly dedicated the song to the IDF soldiers but, when he came here the last time, in 2009, he also wanted to perform in Ramallah [which didn’t materialize], and he donated part of his takings from his concerts in Israel to an organization that supports bereaved Israeli and Palestinian families.”

Such was Cohen’s nature, and his soul searching continued unabated till the end of his life, in 2016.

While the troops Cohen met and performed for deep in the desert got a real tonic out of the musical vignette in the violence, one soldier seemed less enthralled with the balladeer’s efforts.

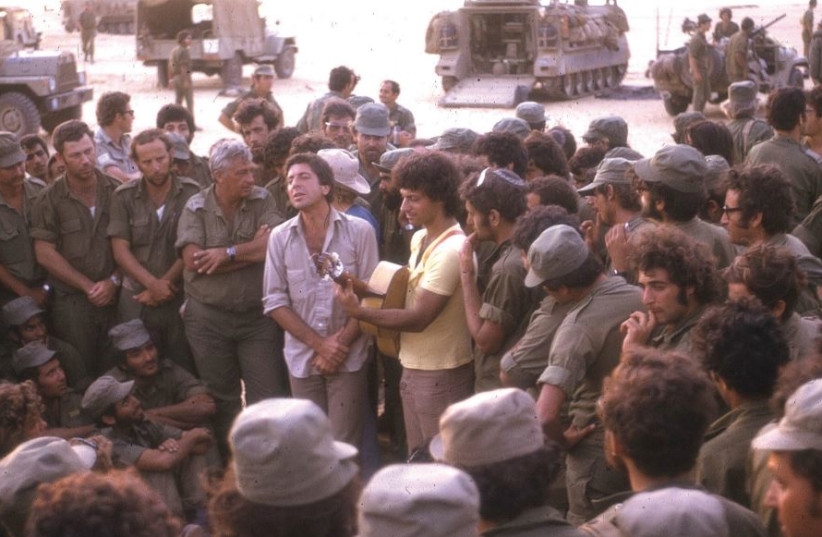

ARIEL SHARON was a division commander during the Yom Kippur War and does not come across as being especially intrigued by Cohen’s songs. One shot, taken by IDF photographer Doron Yaacobi, shows Caspi strumming his guitar while Cohen’s facial expression conveys intense emotion. The majority of soldiers crowding around the musicians appear to be taken with Cohen’s delivery, against a backdrop of halftracks and jeeps and sandy expanses. However, Sharon looks like he is more interested in the charms of Rovina standing right next to him.

Besides the mood-lifting rewards of Cohen’s military circuit here, and the subsequent rescue of his then fading career and loss of personal and professional direction, Kutner feels the Canadian’s wartime efforts touched a small sector of the local music community.

“If Cohen influenced any Israeli musicians I’d say it was that he showed it was possible to sing quiet songs, with very poetic texts.” The timing, it seems, was ripe for a more laidback development in the Israeli music industry.

“By chance, then there was much more openness to writing music to poetry,” Kutner adds. “[Seminal poet singer songwriter] Meir Ariel brought out his debut record in 1978. He always said that Leonard Cohen was a big influence on him.”

Cohen also, in a way, brought local ethnic music back home.

When I caught him live the first time, in Manchester in 1976, I was mesmerized by the Armenian bouzouki player in the band. I’d never previously seen non-Western instruments featured in a rock, pop, or folk gig.

It wasn’t long before the likes of Shlomo Bar, with his Habreira Hativit (Natural Gathering) band, began fusing Moroccan, Indian, and other rhythms and textures with Western sounds.

“Cohen showed it was perfectly acceptable to incorporate instruments like an oud or bouzouki. You can’t put the Mizrachi music evolution in Israel down to him,” Kutner says, but, the fact that it is legitimate for a North American pop star to use an oud or bouzouki might not have had an effect on artists like [Mediterranean music singer songwriter] Avihu Medina, but it certainly impacted Western-oriented musicians here.

Cohen clearly left his musical and spiritual mark here 50 years ago and, unwittingly, saved his career in the process. Not a bad return all around.