Oxana Yablonskaya is a survivor. That much becomes abundantly clear when you learn the world-renowned classical pianist is about to mark her 85th birthday in suitable fashion, by performing two concerts on consecutive days, one in Tel Aviv (8 p.m., Charles Bronfman Auditorium) and one in Jerusalem (7 p.m., Mishkenot Sha’ananim). The latter takes place on December 6, Yablonskaya’s actual birthday.

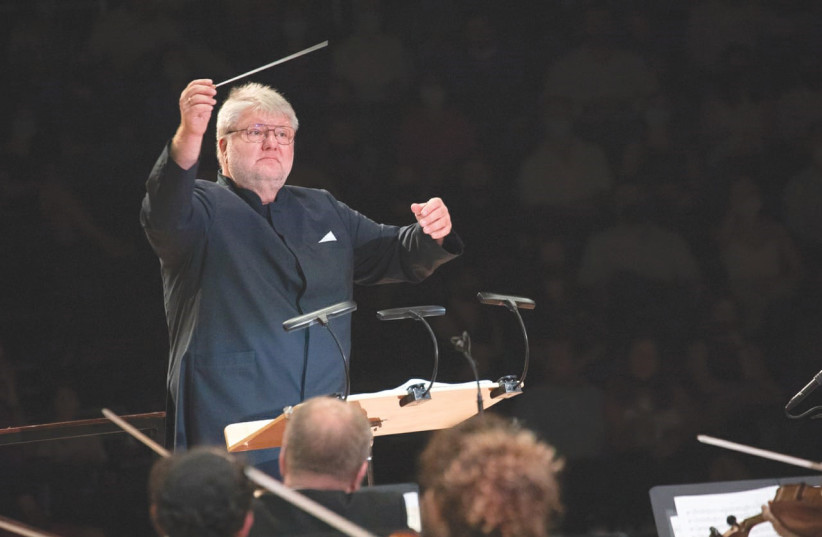

The octogenarian’s sparring partner for the occasion is her acclaimed Grammy-nominated cellist son, Dmitry Yablonsky, who has also made a name for himself in the global arena as a conductor.

Yablonskaya was born in the Soviet Union, which, it turned out, was both a blessing and a curse. Citizens of the Communist regime may not have always been able to lay their hands on a loaf of bread, and Western products such as jeans or Beatles records were either considered contraband or frowned upon by the all-powerful authorities. Then again, cultural fare, such as attending classical concerts or going to see the famed Bolshoi Ballet company, was affordable for most. Education was free, and, certainly in the musical sphere, there were plenty of lauded artists who were also wonderful teachers.

Yablonskaya first laid her small fingers on a keyboard at the age of six. Her natural talent was immediately apparent, and she enrolled at the Moscow Central School for the Gifted, where she made leaps and bounds under the tutelage of Anaida Sumbatyan, a fabled teacher whose stellar students included pianists Vladimir Ashkenazy and Vladimir Krainev.

She took another incremental step in the desired direction when, at the age of 16, she enrolled at the Moscow Conservatory and came under the richly experienced and venerated wing of Alexander Goldenweiser, who was lauded for his instrumental work as well as his skills as a composer. “When I was studying at the Moscow Conservatory and, later, when I was teaching there, that is the place where the greatest musicians teach. In Russia there is a tradition that the best musicians, the best performers, were teaching. That’s not like in the United States.”

The interface with Goldenweiser was a game changer for the young Yablonskaya, and she made significant progress, winning several prestigious competitions and attracting requests to perform around the world.

But, in the bad old Soviet days, that was easier said than done, and all her applications to travel outside the USSR to play for foreign audiences, which would have helped to raise her international profile, were summarily rejected. That must have been exceedingly frustrating. However, the constraints placed on the then-young pianist’s freedom of expression were not restricted to her travel arrangements. “I was invited to play in 21 countries, and I could never go. I only played in [Soviet bloc countries East] Germany and Poland. And I absolutely could not play everything I wanted,” she exclaims. “Some pieces I wanted to play, they said ‘no! you cannot do it.’ It was too modern for them.”

Still, she persevered and did score the odd victory. “I played the Sonata No. 6 by Jewish Polish-born Soviet composer Mieczysław] Weinberg. It is a really interesting piece,” she notes. She says she was often a go-to pianist for various composers looking to air their latest fruits. “I could play all those new things because I learned so fast.”

Making it to the States

EVENTUALLY, YABLONSKAYA’S patience ran out. Despite gaining acclaim in her country of birth, including landing a much-sought after Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra soloist slot and working frequently with the Bolshoi Orchestra, she decided to try to make a break for much larger and more open waters abroad. She, her husband, and cellist son applied to leave for the United States, and she became what she calls “a refusenik.”

It took two long years, during which neither she nor Yablonsky could work, before they eventually moved Stateside in 1977. Their cause was supported by no less than 75 prominent musicians, actors, composers, and politicians, including Leonard Bernstein, Katharine Hepburn, Henry Miller, and Nobel Prize laureate Isaac Bashevis Singer, with even US president Jimmy Carter putting in his lofty pennyworth.

Once ensconced in New York, Yablonskaya began teaching at the famed Juilliard School for the performing arts, and took on a busy schedule of concert engagements. Many of those found her working alongside her son.

“Dima and I have always played together, for so many years,” she declares. “I like so much to play with him, and also when he is conducting. We know each other so well.”

Yablonskaya clearly trusts her acclaimed cellist-conductor son to provide her with the requisite support and freedom of maneuver on stage.

I noted the varied nature of the repertoire for the forthcoming concerts, which takes in works by Vivaldi, Beethoven, Schumann, Shostakovich, and Chopin.

“Dmitry chose it,” she simply says. “We play a lot of things, and I said to him ‘What do you want to play?’ and somebody wrote a special piece for us, but he’s not here at the moment, so we can’t play it. But it’s very nice music anyway,” Yablonskaya laughs.

There’s no arguing with that. And there is only one work by a Russian composer in there. Some try to pigeonhole artists, in various disciplines, and attach generic national cultural traits to their output. There have been those, for example, who have described Russian-born instrumentalists with the “romantic” tag. But as far as Yablonskaya is concerned, it is the individual person, not their environmental backdrop, that comes out in their art.

That is particularly true now, as she moves through her golden years. She says she now approaches music with a different mindset. “With Dmitry, I played with him as soon as he took a cello in his hand. When he was 19 we played a big concert at Carnegie Hall together. I always play with him,” says the proud mom. “Myself I have changed. I now know how older people play. I think that, maybe, you can be sometimes afraid you cannot control yourself.” She says she is now more her own person, on stage and in the classroom, as she makes her frequent working visits to far-flung venues and schools. She appears to be aging well. “I just played in Los Angeles, where a lot of my students live. They said I play better now.”

She appreciates the kudos and says she has no concerns about the praise going to her head.

“I used to be a little bit modest, but now I don’t care about anything,” she laughs. “I play myself.” With close to six decades behind the ivories, that’s a lot to play.

After around four decades in the States, Yablonskaya finally made the move here, taking up a teaching position at the Jerusalem Academy of Music and Dance and continuing to perform here, there, and everywhere. “I always wanted to make aliyah, but, back then, we didn’t have any family here,” she notes. “I feel very Israeli, even though I don’t know much Hebrew.”

Yablonskaya believes she and her fellow professionals have a duty to keep up the good artistic and soul-enriching work in these troubled times. “I think canceling or postponing the concerts will give our enemy a small victory. The Israel audience needs a musical respite, and it is the right answer to terrorism. This is life.”

For tickets: https://kupatbravo.co.il/announce/76611