“I’m not that stupid,” said the then-Prince Charles in a BBC interview in 2018. “I do realize it’s a separate exercise being sovereign. The idea that somehow I’m going to carry on exactly in the same way is complete nonsense.”

His comment reflects the fact that during his 70-year apprenticeship as heir to the British throne, he acquired the reputation for espousing a variety of causes close to his heart and lobbying for them in ways which sometimes aroused surprise, or even controversy. A question often asked in those years was whether he ever would, or indeed could, change direction.

Like his father, Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, Charles as heir to the throne had no constitutional role. Elizabeth II, the British monarch, was head of state. Philip her consort, and Charles her heir, had either to live purposeless lives or else forge meaningful careers for themselves. It is a tribute to them that they both managed to do the latter.

The personal interests and ventures of King Charles

As Prince of Wales, Charles was the patron or president of more than 400 organizations, and in 1976 he founded his own flagship charity, the Prince’s Trust, to connect with what he called the “hardest to reach in society.” It has helped close to a million disadvantaged young people from some of the poorest parts of the country transform their lives by providing them with education, skills and employment. He set it up against government opposition.

“The Home Office didn’t think it was at all a good idea,” he once said. “It was quite difficult to get it off the ground.”

As prince, he was able to act independently. As monarch – and about this he is fully aware – he must act only on government advice. That lesson was made clear at the moment of his accession, when a projected trip to the Middle East was canceled. Charles, a lifelong environmental campaigner, had planned to give a speech at the 27th UN Climate Change Conference (COP27), taking place in Egypt’s Sharm el-Sheikh between November 6-18. He canceled the trip, the media reported, on the advice of then-prime minister Liz Truss, probably taking into consideration the political implications of the new monarch’s first overseas visit.

It was in 1984 that Charles first burst into the headlines as an independent and controversial voice with what became known as his “carbuncle speech.” Of all the things he has ever said in public on matters of policy, this is what will probably never be forgotten, both for his colorful language and for the impact it had on UK society. It proved to be the opening of his decades-long campaign of opposition to modern architecture.

The occasion was the 150th anniversary of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA), the setting Hampton Court Palace. Charles had been invited to present the Royal Gold Medal for Architecture to Indian architect Charles Correa. Rather than handing over the award with a few gracious words, as was expected, Charles seized the opportunity to denounce a proposed extension to the National Gallery. The National Gallery flanks one side of Trafalgar Square, in the very center of London’s West End. Designs for an extension to house Britain’s collection of early Renaissance paintings had been put up for competition, and out of seven entries the design submitted by the architectural firm ABK had been adjudged the winner. Plans were proceeding for its erection.

Choosing his words carefully, what Charles objected to was attaching a modernist structure to buildings constructed in the architectural style of a century and a half earlier. “I would understand better this type of hi-tech approach,” he said, “if you demolished the whole of Trafalgar Square and started again with a single architect responsible for the entire layout. But what is proposed is like a monstrous carbuncle on the face of a much-loved and elegant friend.”

“I would understand better this type of hi-tech approach, if you demolished the whole of Trafalgar Square and started again with a single architect responsible for the entire layout. But what is proposed is like a monstrous carbuncle on the face of a much-loved and elegant friend.”

Then-Prince Charles

A veritable hurricane of comment, both denunciation and approval, followed. But in the end, the ABK scheme was abandoned in favor of a more modest design. Charles’s interest in architecture, though, continued unabated. In 2009, eminent British architect Richard Rogers blamed the prince for having him removed from a project to redesign Chelsea Barracks in West London. “We had hoped that Prince Charles had retreated from his position on modern architecture,” he told the media, “but he single-handedly destroyed this project.”

A few years after the carbuncle speech, Charles’s concerns about modern architecture led him to take the lead in an experiment in urban development – constructing a completely new town from scratch. Poundbury, in the county of Dorset, is designed entirely on traditional architectural lines and is generally judged to be a great success. The work was sponsored by the royal Duchy of Cornwall, which is historically the preserve of the Prince of Wales. Charles handed the duchy and its interests to his son, Prince William, shortly after acceding to the throne.

Over the years, Charles has far from confined his passions to architecture. He has proved a tireless activist in support of a range of issues that concern him, from organic farming to homeopathy, from youth to the environment. He soon learned that his unique position in the Establishment meant that his opinions were always heard and often made a difference. He lobbied in a variety of ways, one of which itself caused major controversy a few years ago – the so-called “black spider memos” affair.

As a key weapon is his lobbying arsenal, Charles took to addressing government ministers, from the prime minister downwards, in a continual stream of memos and letters, handwritten by him in black ink. These documents, which came to be known as his “black spider memos,” were sent by Charles in a private capacity. But when news about them reached the media in 2005, it was thought they might represent the exercise of undue influence over British government ministers, and demands were made for them to be made public. Battles between the media and the government ensued, finally reaching the courts.

After several legal cases, the Supreme Court in 2015 allowed for the publication of the letters. However, on their release, the memos were described in the media as “underwhelming” and “harmless” and as having “backfired on those who seek to belittle him”.

Charles, who has always been aware of the importance of religious belief in people’s lives, has actively supported the organizations representative of the many faiths practiced in modern Britain. He has shown a particular interest in the Jewish community and in (the late) chief rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks. That friendship is now extended to the UK’s new Chief Rabbi, Ephraim Mirvis.

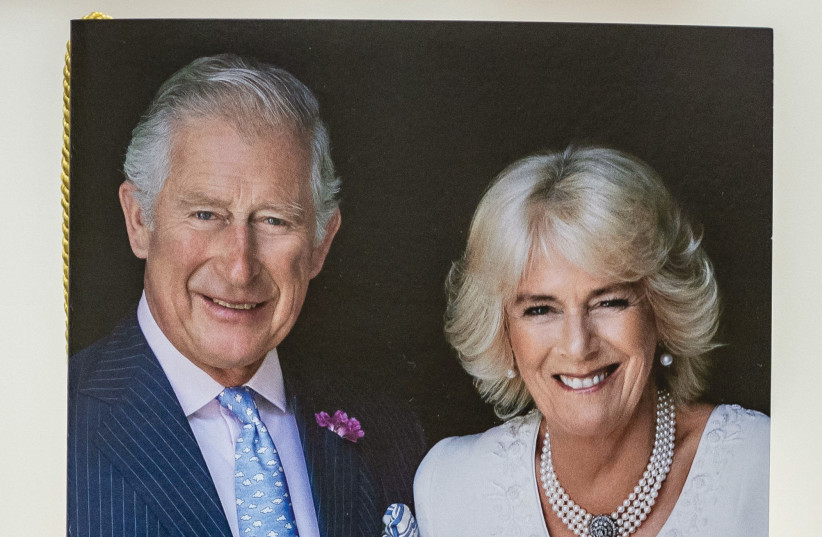

Charles’s coronation is scheduled for Saturday May 6, 2023. To assist Mirvis observe the Sabbath, the king and queen consort have invited him and his wife, Valerie – after they have attended Shabbat service with local communities – to stay with them at Clarence House on the Friday night. Westminster Abbey, where the coronation will take place, is less than a mile away.

Charles is not likely to lose his innate sympathy with the many causes close to his heart, but he has certainly taken on board the fundamental difference in how he may do so, compared with his previous incarnation. William Shakespeare, as ever, has precisely the right words, which he puts into the mouth of the young Henry V as he is about to be crowned:

Presume not that I am the thing I was,

For God doth know, so shall the world perceive

That I have turned away my former self.

Presume not that I am the thing I was/ For God doth know, so shall the world perceive/ That I have turned away my former self.

Henry V, per William Shakespeare

During the coronation ceremony in Westminster Abbey, Charles will be asked if he is willing to assume the awesome responsibilities of being the sovereign head of state of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and of his other realms and territories, and head of the Commonwealth.

In doing so, he will certainly be bringing a difference in tone to the monarchy – a greater awareness of, and in many cases a greater sympathy with, the issues that most concern today’s Britain.

Over the years of his apprenticeship, the public has come to respect him for his causes, and in many cases has come to see that he was ahead of his time in advocating them – issues such as organic farming, climate change, wildlife preservation, and alternative therapies.

Beneath the robes of state he will, of course, be the same man, but no one is more acutely aware than he that in future his actions must be subject to his new status. ■