When I was growing up in Montreal, I lived next door to a couple who were Holocaust survivors – survivors of Auschwitz (more accurately, Auschwitz–Birkenau). Later, I married one of their daughters, and they became my in-laws.

Sarna, who passed away in 1992, was an outgoing and active woman and an excellent seamstress. Watching her at a sewing machine was impressive, particularly because parts of her right-hand thumb and index finger were missing.

Sarna was from Zwolin, a Polish town near the industrial city of Radom, about 60 miles south of Warsaw. She survived the Holocaust as a slave laborer in ammunition factories, at first at a location near her hometown and later at Auschwitz. She lost parts of her fingers after a moment’s inattention at a metal stamping machine. This likely happened at the first site. A compassionate German overseer was able to keep her out of sight during the workdays until the stumps had somewhat healed.

I thought of Sarna while watching an inspiring and poignant documentary, The Heart of Auschwitz. Released in 2010, it is about Fania Fainer, a Canadian Holocaust survivor, who had received a paper heart as a gift from her co-workers for her 20th birthday on December 12, 1944.

Fania and her co-workers were slave laborers in the Weischel Union Metallwerke munitions factory set up at Auschwitz in 1943. The Union, as it was called, was a large ammunition factory with about 2,000 workers, mostly young Jewish women. The paper heart, two inches in diameter when folded, is covered with purple cloth with Fania’s initial embroidered on it. It opens into eight paper sheets covered with penciled birthday wishes from her friends, in various languages. The immense risks taken by the young women who crafted this gift for their friend, using forbidden items, cannot be overstated.

With the Soviet army rapidly approaching, Auschwitz was evacuated by the Nazis a few weeks later, in mid-January 1945. The prisoners were forced to travel long distances, often on foot, without food or water or proper winter clothing. Stragglers were shot by the wayside and many, if not most, did not live to see the end of the war. (Sarna often spoke of “the death march.”) Fania kept the heart by hiding it under her arm. It stayed with her as the only remnant of her past as she rebuilt her life in Canada after the war.

She donated the heart to a Holocaust museum in Montreal, where it attracted the attention of film director Carl Leblanc. Leblanc’s effort to locate at least some of those who contributed to Fania’s gift is the primary focus of his film. The quest took him to a number of international locations, including Israel. It was a formidable task, partly because more than 60 years had elapsed but also because the signatures on the heart did not include surnames.

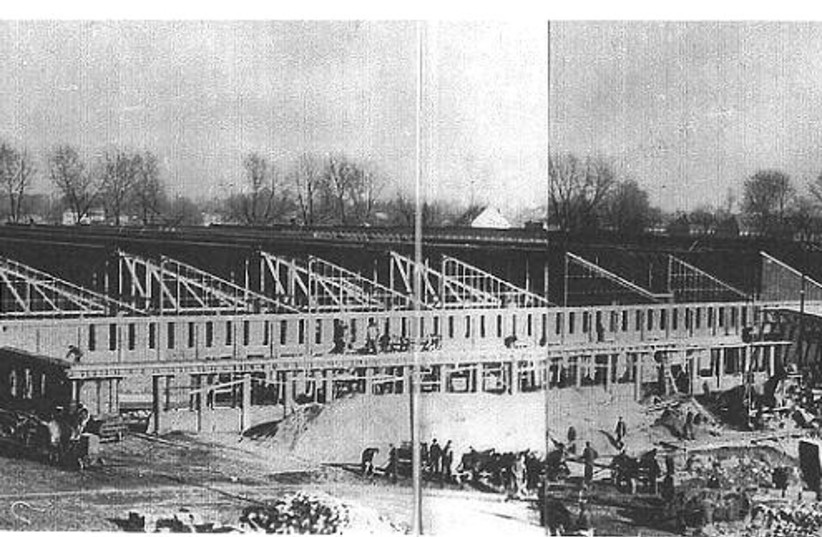

The heart is now part of an educational program operated by the museum. The final and most touching portion of the documentary shows Fania interacting with students and their teachers. The documentary also includes a segment in which Fania’s daughter and granddaughter are on a tour of Auschwitz. While it is a derelict today, the Union building still stands. I was surprised to see how large it was; but I shouldn’t have been. Sarna used to say that you could not see from one end of the building to the other.

After watching the movie (twice), I discovered that an Auschwitz-Birkenau survivor had produced a book consisting of 36 personal accounts by survivors of the Union factory at Auschwitz. The book, The Union Kommando in Auschwitz, a trove of first-person experiences, translated and edited by Lore Shelley, was published in 1996. The author is no longer alive. The book is out of print, and used copies are not easy to obtain. This is a shame, since this book documents an important aspect of Holocaust history not covered by other resources. Fortunately, I was able to borrow a copy from a nearby library.

Most of the contributions are relatively short biographical descriptions that portray pre-war life, along with the steps that led to the Union. Several are longer and more expansive. That of Lidia Vago, a Union survivor living in Petah Tikva, who appeared in Leblanc’s film and helped him find survivors connected with Fania’s heart, is 25 pages long.

Herman Haller (USA) described how the dehumanization process employed against the Jews was a long and gradual process initiated by the Nazis in 1933. It began with boycotts of Jewish stores, then the Nuremberg Laws, deportation to concentration camps, being reduced to a mere number, extermination through labor, ending with the Final Solution – the goal from the beginning.

Yehuda Laufer (Israel) addressed the difficult topic of the kapos, Jewish and non-Jewish prisoners forced to act as enforcers for the Germans running the camps. He wrote, “It is impossible to explain the fear, pain and helplessness and other emotions confronting someone with the choice of ‘to be or not to be.’ In my opinion, whoever has not faced such a dilemma should not judge.”

“It is impossible to explain the fear, pain and helplessness and other emotions confronting someone with the choice of ‘to be or not to be.’ In my opinion, whoever has not faced such a dilemma should not judge.”

Yehuda Laufer

Working in the Union improved one’s chances of survival

One thing is clear: Working in the Union improved one’s chances of survival. The work was carried out indoors and, unlike the situation in the general barracks, normal toilet facilities and showers were available to the workers. In addition, the food rations were slightly better.

A number of the contributors referred to the loss of fingers. Sándor Schwarcz (Hungary) noted that one worker, who lost two fingers, was sent to the gas chamber. Judith Newman (USA) noted that there were incidents every night involving workers who lost two or three fingers.

The munitions factory was originally located in Essen, Germany, and was part of the Krupp conglomerate. It was heavily bombed by the Allies, and a decision was made to move it to Poland to be farther away from the bombers. A large IG Farben plant manufacturing liquid fuels and synthetic rubber was already near the site. Placing the munitions factory inside Auschwitz made it easier to use the prisoners as free labor. Krupp’s effort to move machinery to Auschwitz was foiled when the train carrying it was bombed, and ultimately it was Weischel Union Metallwerke that took over.

The saga of the Union factory in Auschwitz includes an episode of unparalleled heroism and sacrifice. On October 7, 1944, the Sonderkommando at Auschwitz revolted, killing some of the German guards, as well as setting fire to and blowing up one of the crematoria. The Sonderkommando (or special commando) was made up of prisoners, usually Jewish, who, among other tasks, were forced to remove the bodies from the gas chambers and incinerate them in the crematoria.

The revolt took place when the Sonderkommando learned that their own executions were pending and after the rebelling prisoners had accumulated gunpowder smuggled to them by women working in the Union. In the end, all 600 members of the Sonderkommando were killed. The Nazis could only identify four of the roughly 30 women involved in the smuggling operation. Despite undergoing terrible tortures, the four women refused to divulge additional names. They were hanged in public on January 6, 1945, less than two weeks before the evacuation of Auschwitz. As Dr. Israel Gutman (Israel) put it in The Union Kommando in Auschwitz, “In the gigantic camp, where tens of thousands of prisoners were confined, a handful of Jews burst through the pervasive spirit of submission…”

The Sonderkommando revolt, and other revolts by Jews experiencing the Holocaust, fly in the face of the widespread view that the Jews did not fight back.

One final point: The refusal by the Allies to bomb the railway lines into the Auschwitz-Birkinau complex during the later stages of World War II, even after credible reports exposed the mass extermination of Jews and others that was taking place, has become a controversial Holocaust issue. After all, the nearby IG Farben plant was bombed more than once, why not Auschwitz? The primary response of the American administration to such questions was that it was essential to end the war as quickly as possible by focusing on targets of military value. Did they know that the concentration camp contained a large munitions factory? Would it have made a difference if they did? ■

Jacob Sivak, a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, is a retired professor, School of Optometry and Vision Science, University of Waterloo.