“We want fish. We want fish!” These ridiculous chants boomed through the Jewish camp, as an angry mob clamored for a return to Egypt.

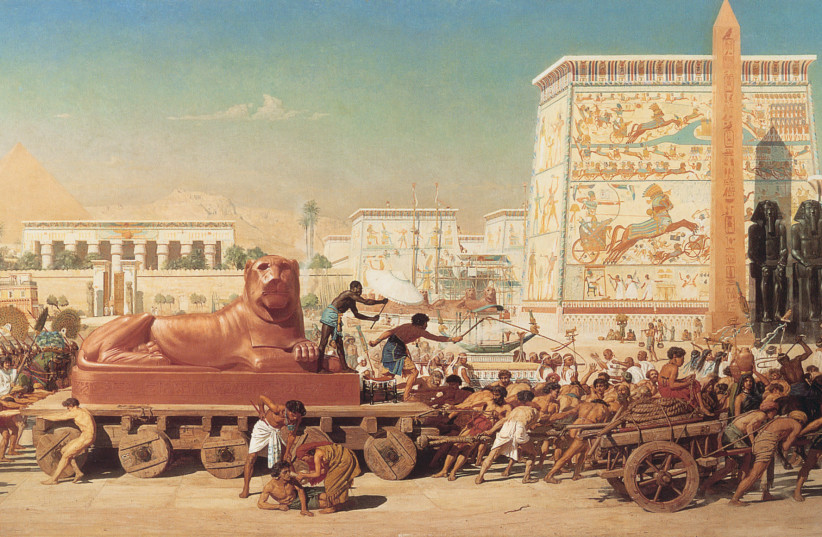

Astonishingly, the hordes demanded a return to oppression and a return to the puny and putrid scraps of fish they received at the end of each dreadful day of labor.

People always yearn for the “good old days” but often, those old days weren’t that good to begin with. What lies at the heart of this illusion about the good old days? What incited this ludicrous demonstration in the desert?

In part, the Jews were suffering from a form of prisoner anxiety. Freedom carries great weight and great personal responsibility. Often, the burden of freedom is too difficult to bear, especially for people who have enjoyed the tranquility of a life without choice. Imprisonment and slavery snatch away freedom of choice, and relieve us of the heavy burden of decision-making.

The former Jewish slaves now faced a frightening march through the desert, as well as the daunting challenge of conquering the Promised Land. As adversity set in, it was easier to flee these challenges and escape back to their prior state of slavery – a world without heavy expectations and a world in which they could rely upon their daily fish as a given. Facing a choice between fish and freedom, these panicked slaves chose fish.

In addition to fearing their freedom, the Jews fell into a well-known psychological trap – the deception of nostalgia. Nostalgia allows our memory to selectively choose moments from our past, which, when dusted off and polished, appear shinier than our dreary present. We recall our past in a manner that our brains choose to remember it, and we imaginatively reinvent and glorify that past. As the past is unaffected by the struggles and hardships of the present, it always seems more radiant, more dazzling and more perfect. Often, anxiety about our current state drives us into unrealistic memories of a better past.

Sometimes we experience collective nostalgia – not about our personal past but about past generations. Facing problems and challenges in our own societies we often look to previous societies as more successful versions of the human experiment. We convince ourselves that our current world is dysfunctional and beyond repair; once convinced of our own ineptitude, we exonerate ourselves from improving our contemporary condition. Personal and collective nostalgia often provide easy escapes.

For Jews, the challenges of generational nostalgia are particularly complex. We are often nostalgic about past generations, viewing them as religiously and spiritually superior to our own fallen state. This view is captured by the concept of “nitkatnu hadorot,” which asserts that later generations have literally become “smaller” and are in constant state of religious decline.

Is this completely true?

Does the passing of generations bring with it religious deterioration, and is a later generation, by definition, spiritually inferior to previous generations? In some ways this is true, but in many other ways it isn’t.

Jewish faith and the transmission of Torah both emanate from one seminal event that occurred 3,300 years ago. On that epic day, God directly revealed Himself to more than 3.5 million people, and this once-in-history event never recurred. Those who lived in closer proximity to that event, obviously, possessed a more accurate transmission than those who lived historically removed from “the source.”

In addition to their proximity to Sinai, those who lived through the ensuing 1,300 years of prophecy enjoyed supernatural access to heavenly information. Certainly, our collective level of religious knowledge cannot possibly match the achievements of generations upstream in Jewish history.

If earlier generations possessed greater Torah knowledge, we would expect their moral and religious behavior to be equally surpassing. Often this was true, but, sadly, human experience doesn’t always match expectations.

During the First Temple era, our religious behavior was abysmal. Widespread violation of cardinal religious prohibitions doomed the great potential of that period and sentenced our people to its first exile. We were far too confident in our land and our temple, and we naively believed that God would protect us from any, and all, calamities. Convinced of our invulnerability, we committed terrible sins. Our careless religious lifestyles wrecked our national potential and condemned the temple.

Throughout our extended exile we also experienced periods of religious letdown. Unsurprisingly, the more Jews were persecuted, the greater religious resolve we displayed; the more comfortable our surroundings and the greater the cultural embrace of Jews, the more our religious resolve atrophied. 15th-century Spain and 19th-century Eastern Europe provide two examples of religious regression prompted by excessive acculturation. It is not always true that past generations exhibited greater religious commitment.

There is an additional area in which successive generations don’t necessarily retreat. Sometimes, later generations exhibit faith that far surpasses the courage of previous generations. Certain generations display uncommon fortitude in the face of excessive hostility. For example, the bravery of the Jews living under Roman persecution in the 1st and 2nd centuries was legendary. Known as the “dor hashemad,” their courage in defying the Roman Empire reinforced Jewish religion and pride and paved the way for the emergence of the Talmud.

Our own generation has displayed similar national valor. Our generation has faced two daunting challenges, unimaginable to previous generations. After the nightmare of the Holocaust, our people were tasked with rebuilding Jewish communities and reconstituting the Jewish spirit. Over the past 80 years, we have heroically rebuilt the foundation of the Jewish world and restored a sense of Jewish communal belonging.

Alongside the mission of recovering from the Holocaust, we have also been challenged to rebuild and resettle our ancient homeland in the face of unrelenting opposition and constant invasions. Jews around the world have lobbied together to craft this historical miracle, despite the hatred and violence directed against us.

The concept that generations deteriorate can be very misleading, and, worse, can become very enfeebling. Viewing ourselves as midgets can become a self-fulfilling prophecy. Convinced of our own helplessness, we become incapable of greater aspirations and too frail for great accomplishments.

Jewish tradition is definitely built upon a hierarchy that acknowledges the authority of past generations. However, each generation faces its own historical setup, and some generations display great heroism, courage and commitment in facing off against history.

Our generation has much to be proud of. ■

The writer is a rabbi at Yeshivat Har Etzion/Gush, a hesder yeshiva. He has smicha and a BA in computer science from Yeshiva University and a master’s degree in English literature from the City University of New York.