The title page of the popular hassidic work Maor Vashamesh has an anomaly.

According to standard printing mores, the name of the printing press and the year of publication are given on the lower third of the title page. According to the Maor Vashamesh title page, the volume was published at the printing press of Rabbanit Mrs. Yehudit Rubinstein in the Hebrew year 5545, which is 1784/5. The place of publication is missing – an irregular omission that sows a seed of suspicion.

In the center of the page, the author’s name – Rabbi Kalonymus Kalman HaLevi Epstein – is given in bold letters together with two abbreviations after his name. Those abbreviations indicate that he had already passed away: “May the memory of the righteous and holy person be a blessing, for the life in the world to come. May his merit protect us. Amen.” This is where it gets sticky: Rabbi Kalonymus Kalman passed away in 1823, making him very much alive in 1784/5 when the book was purportedly published.

Which detail is accurate? Was the book really published in 1784/5 when Rabbi Kalonymus Kalman was still alive, or was it published after 1823? The solution to that riddle can be found in the front matter of the volume.

In the letters of approbation for the volume, as well as in the introduction penned by Rabbi Kalonymus Kalman’s son, there are repeated references to the author’s demise. One of the approbations also carries a Hebrew date corresponding to Wednesday, March 4, 1840. Another approbation was given by Rabbi Dov Berish Meisels (1798-1870) – who was not even born in 1785 when the book was allegedly published! So clearly the work – at least as it has reached us – was not published in the 18th century.

The title page indicates this is part one of the work, and part two of the work opens with another title page. The author’s name is given with the same honorifics for the deceased, but the lower third of the page offers different imprint information: the book was published in Breslau in the printing press of Hirsh Zaltzbach in the Hebrew year 5602, that is 1841/2. Based on the dates mentioned in the front matter, this date is plausible.

Who was the real printer: Rabbanit Mrs. Yehudit Rubinstein or Hirsch Zaltzbach?

Hirsch Zaltzbach was indeed a publisher in Breslau. The printing business was originally owned by his father Leib Zaltzbach. From 1829, the father and son worked together. Books published from 1835 through to 1864 carry Hirsch’s name alone.

What about Rabbanit Mrs. Yehudit Rubinstein? Alas, we have no record of a Yehudit Rubinstein operating a printing press – not in Breslau, nor anywhere else. In fact, this is the only book that carries that name in the imprint information.

Moreover, some surviving copies of that first edition have a title page that includes what must be the accurate information: Maor Vashamesh was published by Hirsch Zaltzbach in Breslau in 1842, after the author Rabbi Kalonymus Kalman HaLevi Epstein of Kraków had passed away.

Why were some copies of the first edition of the Maor Vashamesh printed with a false title page? Is there significance to the fake imprint year 1784/5? Why was the name Rabbanit Mrs. Yehudit Rubinstein used? These questions are yet-to-be-solved mysteries...

THERE IS no escaping the conclusion that there was no printing press operated by a Rabbanit Mrs. Yehudit Rubinstein. Notwithstanding this conclusion, many women were actively involved in the enterprise of publishing Hebrew books, including hassidic works. In fact, Maor Vashamesh itself was later printed by a woman: Pessel Balaban.

Pinhas Moshe Balaban inherited a printing press in Lemberg from his father. Together with wife, Pessel, Pinhas Moshe operated the press. Pessel’s name appears next to the name of her husband on a number of titles from the year 1863.

The following year, 1864, Pessel’s name appears as the sole printer of the first volume of what would become a five-volume set of the Pentateuch that included the commentary Heikhal Habrakha by the hassidic master Rabbi Yitzhak Eizek Yehuda Yehiel Safrin of Komarno (1806-1874).

That year must have been a busy year for Pessel, as her printing press also published an edition of Psalms, as well as a volume of slihot – the penitential prayers said on fast days and during the High Holy Day period.

In 1869, Pessel issued a different edition of the Five Books of Moses. That edition included various classic commentaries, including the hassidic commentary Maor Vashamesh!

Rabbanit Mrs. Yehudit Rubinstein may not have merited to have a hand in the dissemination of Maor Vashamesh or other hassidic teachings, yet Pessel Balaban did realize that dream.

IT WAS not just Jewish women who published Hebrew books. Johann David Grillo (1684–1766) was a German professor of philology and theology who was involved in Hebrew printing. In 1746 in his Frankfurt-an-der-Oder printing press, he produced a five-volume Pentateuch replete with classic medieval commentaries.

For the next 20 years, Prof. Grillo continued printing Hebrew books. With Prof. Grillo’s death in 1766, his widow took over the operation. She immediately continued publishing Hebrew titles. The title pages of her books consistently note that they were published “in the house and at the printing press of the widow of the master, doctor, and professor Grillo.” Mrs. Grillo’s first name is not given.

After Mrs. Grillo’s death, the printing press passed to the daughter of Prof. and Mrs. Grillo. She continued publishing Hebrew books. Her first name also does not appear on the title page. The daughter followed the style of her mother, stating that the works were published “in the house and at the printing press of the daughter of the master, doctor, and professor Grillo.”

All told, close to 80 Hebrew titles were printed by the Grillo publishing house in Frankfurt-an-der-Oder. This is an impressive achievement, especially when we consider that the Grillos were not Jewish.

THUS WOMEN – Jewish and non-Jewish – operated printing presses and were actively involved in the enterprise of publishing Hebrew books, including hassidic works.

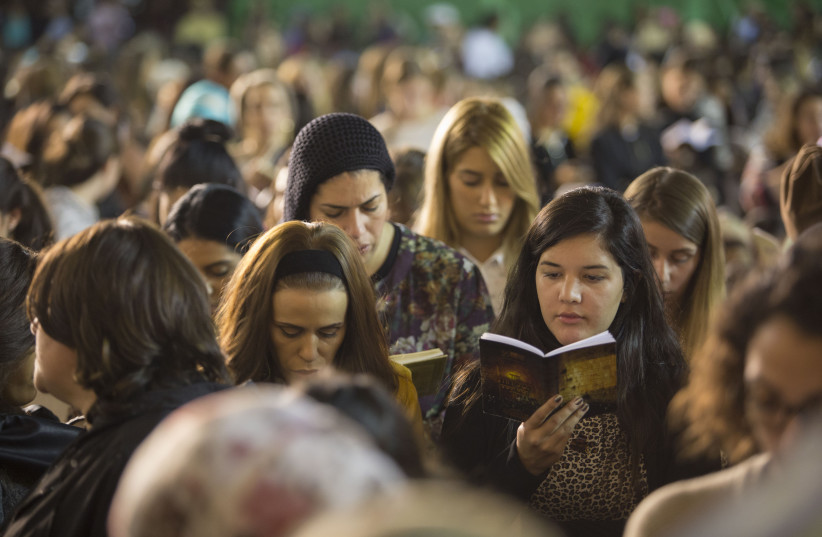

Women’s leadership roles in the hassidic movement are seldom given prominence. The printing press is one place to look when considering women’s contribution to hassidism. Their involvement in the dissemination and spread of hassidic ideas is immortalized on the title pages of hassidic volumes.

The writer is on the faculty of Pardes Institute of Jewish Studies and is a rabbi in Tzur Hadassah.