With the arrival of Sukkot, we leave behind the confines of the 10 Days of Repentance and begin our engagement with the new year afresh. Chag Hasukkot, the Festival of Booths (Lev. 23:34) as it is called in this week’s Torah reading, is also referred to (in this week’s reading) simply as “chag” (holiday) (Lev 23: 39,41). That name, with its focus on joy (Lev. 23:40), can be understood as the imprint for the other holidays of the calendar.

The last sentence from the Torah reading for the first day of Sukkot is: “And Moses declared to the Children of Israel the appointed seasons of the Lord” (Lev. 23:44). This versatile sentence points to the uniqueness of each holiday and is not only a part of the liturgy of the day, which we will explore. It became the basis for a number of significant lessons on ways to observe and celebrate the festivals.

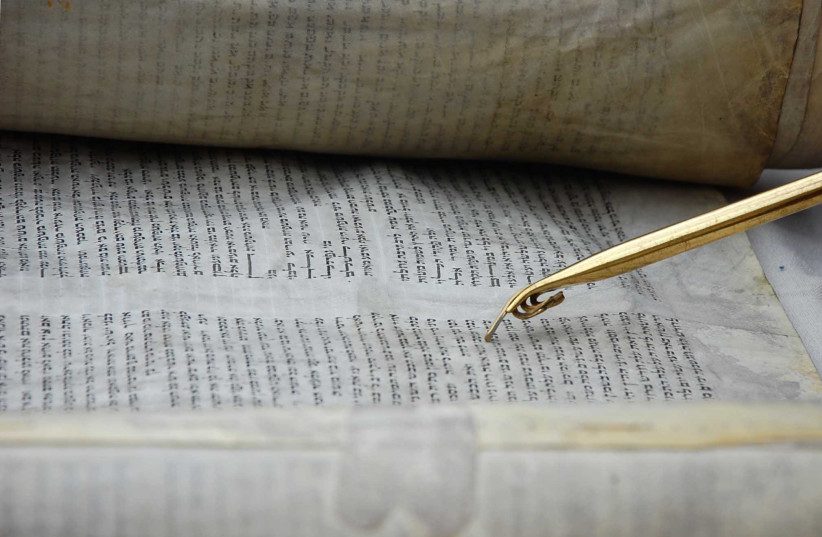

For example, it was established that the Torah should be read not only on Shabbat but on the holidays as well: “Moses warned Israel that they should read out of the Torah on Sabbaths, festivals, new moons, and the intermediate days of the festivals; as it is stated, ‘And Moses declared unto the Children of Israel the appointed seasons of the Lord’” (Soferim 10:1).

What do you read from the Torah on holidays?

That raised the question about what, exactly, should be read from the Torah on those festive days. The answer being something relevant to the particular holiday: “On festivals and holidays, they read a portion relating to the character of the day, as it is stated: ‘And Moses declared to the Children of Israel the appointed seasons of the Lord,’ which indicates that part of the mitzvah of the festivals is that the people should read the portion relating to them, each one in its appointed time” (Megillah 31a).

In addition, on those holidays we should not only read something from the Torah pertinent to the holiday, but we should also discuss how to consecrate the particular holiday.

The Mishna states: “The verse ‘And Moses declared to the Children of Israel the appointed seasons of the Lord’ indicates that part of the mitzvah of the festivals is that they should read the portion relating to them, each one in its appointed time.”

The sages taught in a baraita (oral tradition not included in the Mishna) that Moses enacted for the Jewish people that they should make halachic inquiries and expound upon the matter of the day. They should occupy themselves with the halachot of Passover on Passover, with the halachot of Shavuot on Shavuot, and with the halachot of Sukkot on Sukkot (Megillah 32a).

The question was also asked whether, if a holiday falls on a Shabbat (as the first day of Sukkot this year), we read the parasha that follows the previous week’s parasha. The answer is no, derived from the thinking in this Talmudic discussion of our verse which says that, in certain regards, the holiday abrogates Shabbat:

“It is as the Sages taught based upon the verse ‘And Moses declared the appointed times of the Lord to the Children of Israel.’ This phrase is necessary because we had learned only that the daily offering and the Paschal lamb override Shabbat and ritual impurity, as it is stated with regard to them: In its appointed time, from which it is derived that each of them must be sacrificed in its appointed time and even on Shabbat, in its appointed time and even in ritual impurity” (Pesachim 77a).

Our verse “And Moses declared to the Children of Israel the appointed seasons of the Lord” is used liturgically as the introduction to daytime festival Kiddush. Known as kidusha rabba (the great Kiddush) (Pesachim 106a), it has an interesting history.

According to Rabbi Robert Scheinberg, for several centuries only “borei pri hagefen,” the blessing over the wine, was said for both Shabbat and festival mornings Kiddush, with no introductory words. Scheinberg adds, “It appears that the first source to suggest any additional verses to precede the morning Kiddush on Shabbat is the (13th or 14th century) Kol Bo [a collection of Jewish ritual and civil laws].” Scheinberg also points out that it is unclear when our verse (“And Moses declared”) was actually first used with the morning festival Kiddush, “but the practice of adding that verse during Maariv [the evening prayer], before hetzi kaddish, can be found in Rabbi David Abudraham (13th century), who notes that it’s a practice he has heard was not universal.”

In the evolution of Judaism, the emergence of citing “And Moses declared…” on festival mornings as a preface to the blessing over the wine is cloudy.

Rabbi Michael Strassfeld theorizes: “Perhaps because Leviticus, chapter 23, starts with the verse ‘The Lord said to Moses, ‘Speak to the Israelites and say to them: ‘These are my appointed festivals, the appointed festivals of the Lord, which you are to proclaim as sacred assemblies’ (Lev. 23:1-2). The Mekhilta [compilation of scriptural exegesis] on parashat Yitro sees this verse as the source for saying Kiddush on festivals. It is not clear why they use Lev. 23:44 instead of the earlier verse from the chapter (Lev. 23:1-2), but it serves the same purpose liturgically as the “ve-shameru” said before Kiddush on Shabbat morning. Both introduce the Amidah in the evening service (ve-shameru on Shabbat evening, and “Moses declared” on a festival evening). And both ve-shameru on Shabbat morning and ‘Moses declared’ on a festival morning serve the purpose of making clear that the Kiddush being said is to proclaim and affirm the significance and celebration of Shabbat or of the festival.”

It can also be argued that “And Moses declared to the Children of Israel the appointed seasons of the Lord” (Lev. 23:44) was chosen as the verse to be recited for the festival morning Kiddush because of its broad usage as the source, as we have explored above, for so many different aspects of the festivals. In addition, Leviticus chapter 23, which makes up part of the reading for the first day of Sukkot, includes explanations about Shabbat, Passover, Shavuot, Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur, and Sukkot. That overview, connecting those special days of the year, is bridged by reciting that last sentence of that Torah reading as the part of Kiddush on the festivals.

As Rabbi Sharon G. Forman teaches: “We may believe time moves inexorably forward, but as the holidays loop back around on each other, memories superimpose themselves, one atop another. Rosh Hodesh Nisan reflects not only the forthcoming spring but also Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur all at once.” ■

The writer is a Reconstructionist rabbi emeritus of the Israel Congregation in Manchester Center, Vermont. He teaches at the Arava Institute for Environmental Studies at Kibbutz Ketura and at Bennington College.