Over the years, I have received countless requests from desperate parents looking for emotional and practical support in helping their seriously ill children cope with all sorts of challenges. But there was one particular phone call I received that comes back to me every year as we approach the holiday of Simhat Torah.

On the other end of the line was the mother of a young boy who had a particularly serious and debilitating form of muscular dystrophy. With her voice breaking she told me how her son would cry to her that the saddest time of the year for him was Simhat Torah. While the entire synagogue was dancing and singing with the Torah, her young son was forced to watch from afar. His legs refused to work and the best he could do was roll around on the floor. He certainly wasn’t able to keep up with the fast-moving circles of the rest of the congregation who would look at him with pity; so at some point he had just given up.

“What should be the happiest of days of the year, is just another day of pain and frustration,” the mother cried.

Feeling her pain and knowing that her son was certainly not alone, we made the decision to create a Simhat Torah celebration that would respond to the very unique and challenging needs of these special children.

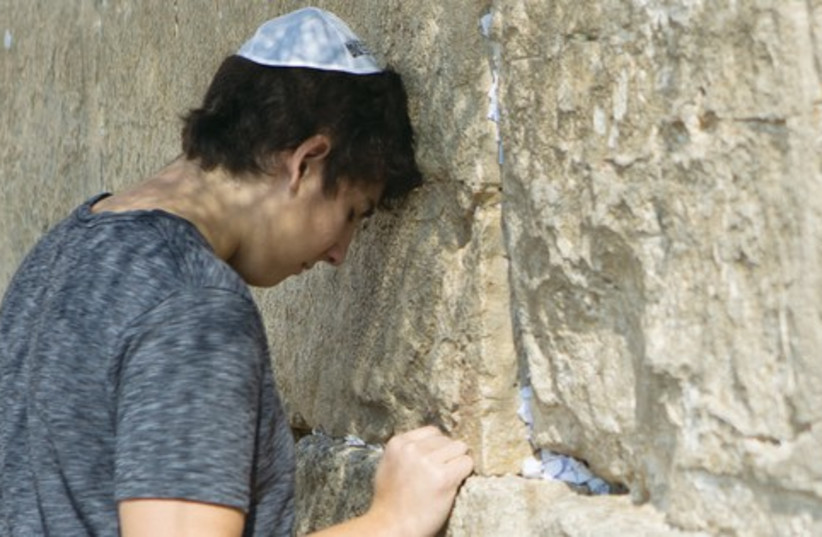

What came about was a moving and truly magnificent experience. These children were wrapped up in an environment where they didn’t feel like charity cases but were among equals. No longer was there any sense of the disabled being excluded. We looked on and realized that dancing doesn’t require legs; a wheelchair can bring just as much joy. The scene of the Torah strapped to a child’s chest because he didn’t have the muscle strength to hold it on his own is one which those in the room will take with them for the rest of their lives.

Our decision to hold this program was also inspired by a famous story told of the great hassidic master Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Rimanov.

The evening of Simhat Torah came and the entire congregation had assembled for the service. The townspeople were gathered in the synagogue and were ready to begin the evening prayers but they couldn’t find their rebbe. A search party went out until they found him dancing with a disabled child in the child’s home.

As they entered the room, they asked him what he was doing there as opposed to being in the synagogue with all his followers? He explained that he had seen the child’s parents go off to the shul leaving the child behind. “If there was one place where I could be sure to find God on this holiest of days it would be here dancing alongside this special boy.”

Sadly, our experience, and that of the hassidic master, represents more of an exception to the rule. For as much as we strive to accomplish as a community in caring for the needs of the disabled within religious settings, the reality is that there is so much more to be done.

We must first begin by changing our perspective. While these children are classically defined as disabled, perhaps that’s not the proper term. Rather they are differently abled.

They don’t deserve to be treated with pity but rather we need to find ways to include them.

From the many years of working with this community, I also know that they don’t want to be “accommodated.” They don’t want to feel that we are being inconvenienced by our efforts to help them. Rather, we need to understand that by including them we are not just helping these children, but rather we are simply doing what is right – which is to treat every child (and every adult) who is facing challenges as equals. I admit that might not be easy because we know they sometimes require additional attention or physical accessibility. But they are no less deserving of being included than each and every one of us who is blessed with good health, mobility or whatever other manifestations distinguish between the enabled and the so-called disabled.

Simhat Torah is both a time of celebration and renewal as we mark the beginning of the next Torah cycle.

But it demands also to be a time of renewal in how we relate to all in our community. Let us internalize the teachings of Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Rimanov, as well as the lesson provided to us by that special boy whose rolling along the floor was as holy as any dancing we would ever witness. For even if we dance differently, we should always dance together, and in so doing we will always find a way to celebrate and live together.

The writer, a rabbi, is the chief executive officer of Chai Lifeline, a leading international children’s health network providing social, emotional, and financial assistance to children with life-threatening and lifelong illnesses through a variety of programs and services.