It has been a fractious time. The Israelites leaving Egypt complain. The Israelites at Sinai build a golden calf. Moses is angry and anguished. What ought one to do?

The question is of more than academic interest. We live in such times. The particulars differ, but the sense of division is deep and seemingly grows each day. People are inclined to blame politics, but political life is not separate from the way we feel and speak about one another. Social media amplifies the divide and exacerbates it.

For all the wonders of the modern world, we are the Israelites at the foot of the mountain, having witnessed miracles that nonetheless do more to pull us apart than bring us together.

One way of creating unity is through enmity. Leaders know that they can bring their nations together if they identify another nation that threatens them, whether it is true or not. An enemy within, an enemy that threatens your border, an enemy that opposes your vital interests – all the varieties of antagonism are wielded by leaders to unite an otherwise divided nation. One solution is the way of war.

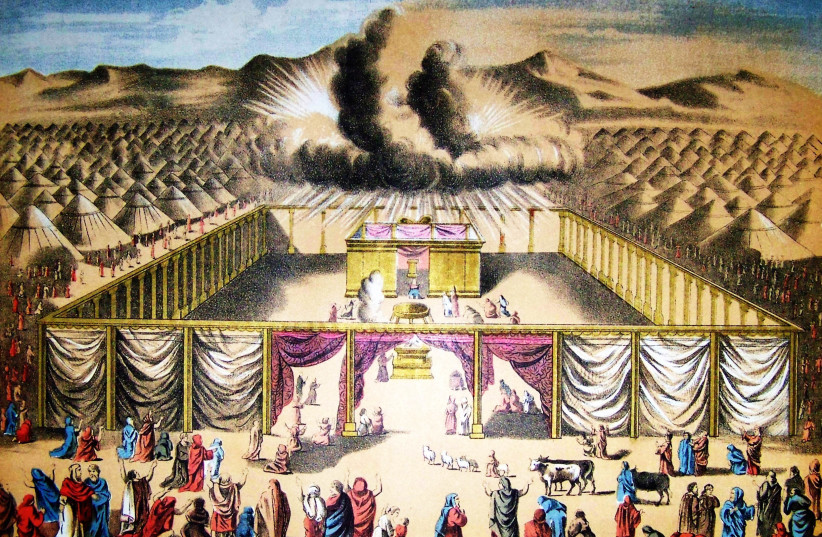

In our parasha however, for the very first time, Moses calls the people together. He does not do so in the face of Amalek or another enemy. War is not Moses’s method of unity. Rather he calls upon all of Israel and starts to tell them of Shabbat and of donating to the Tabernacle.

These two themes have the power to change the moment.

Shabbat can help bring us together because Shabbat is the holiday where material gives way to spirit. Yes, it is true that we put aside special food for Shabbat and bring out a white tablecloth. We do not become non-physical creatures. But everyone, from the most renowned to the least of Israel, is royalty on this day, prays the same prayers and has a moment of soul peace.

Everyone listens to the same Torah reading and is free to learn the same lessons. When we sit together in a congregation, tallitot disguise who is wearing a fancy suit and who is dressed in old clothes, and voices raised together make no distinction between stations of life. We are Clal Yisrael – the people of Israel, standing before God on a day of calm.

The second theme of donating to the Tabernacle is a reminder that there are differences, but everyone is able to contribute something. Remember that God told the Israelites everyone whose heart moves them could contribute – not everyone who is rich, but everyone who is generous.

It is a reminder that we all have something to give to one another and we all have something to learn from one another. Together, we build the means to connect to God.

Those of us who are troubled by the disunity in the Jewish community may take some comfort from our history. This is not the first time there have been fights and fractures, from Korah until today.

Yet here we have Moses calling the people together and reminding them – we have Shabbat, we have a tabernacle. There are ideas and entities that will enable us to embrace one another with all of our differences.

The seventh day is given each week to reflect on the goodness of God’s world and the collective mission of the Jewish people. The tzedakah box stands during the rest of the week to help us build God’s presence in goodness in an unredeemed world.

It was not easy in the time of Moses and it has not grown easier in our own day. But we are still responsible for one another and we still have to hold hands on our way through the wilderness. ■

The writer is Max Webb senior rabbi of Sinai Temple in Los Angeles and author of David: The Divided Heart. On Twitter: @rabbiwolpe