Interview: Dance, dance, dance

A few questions for Yair Vardi, founding director and driving spirit of the Suzanne Dellal Center for Dance and Theater.

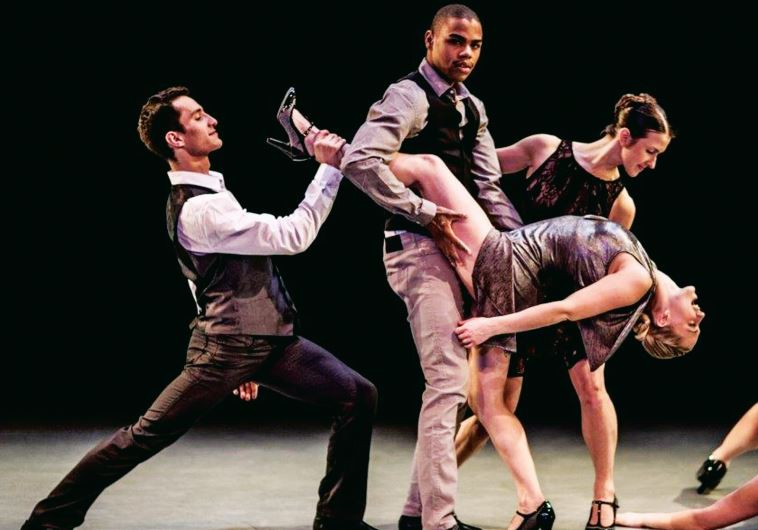

Peridance New York, taking part in this year’s edition of Tel Aviv Dance.(photo credit: DEKEL HAMATIAN)

Peridance New York, taking part in this year’s edition of Tel Aviv Dance.(photo credit: DEKEL HAMATIAN)