It is a pretty safe bet that not too many of us have heard of Yitzhak Yerushalmi. And there are probably not even more than a handful of artist-photographers, academics, and/or curators in the field who are cognizant of the work the now 76-year-old former snapper produced in the 1960s.

Considering Yerushalmi laid down his camera over half a century ago, that isn’t too surprising. Albert Swissa is now trying to do something about the septuagenarian’s low public profile, principally by curating an extensive exhibition of his archival treasures at the Canada House branch of Musrara The Naggar School of Art and Society. The show opened last week and will close on December 6.

The show is running under the Photopoetics category umbrella of this year’s Manofim Jerusalem Contemporary Arts Festival, which was due to take place at venues across the city, for the 15th time, October 24-28. Naturally, the current round of violence put paid to that, as with numerous other cultural events, although exhibitions are beginning to emerge over the nationwide doom and gloom parapet.

Taking place at the Manofim Jerusalem Contemporary Arts Festival

The title of the exhibition gives the game away, although in somewhat subtle fashion, particularly as a result of the linguistic choice. “La Fête Naïve” does roll smoothly off the tongue, even my British-born tongue. It translates as something along the lines of “celebration of naiveté.”

Naggar School chief curator, director, and founder Avi Sabag says the French phrase infers the contrary path Yerushalmi took on his way to satiating his documentary aspirations and finding his own special place in Israeli society. “‘La Fête Naïve’ is Yerushalmi’s inverse journey: from the [sociopolitically accepted] kibbutz to the urban neighborhood, to the immigrant neighborhood to which he returned. The seemingly naïve photographic viewpoint is his own private celebration, through which he rediscovers his own existence which, in practice, had slipped away from him, and in which he repositions himself.”

That sense of innocence and simplicity comes through in all the 100 or so monochrome prints on display on the top floor of Canada House. There is an endearing lack of sophistication about the pictures. Yerushalmi seems to have set out just to document his neighbors in the then maabara (transit camp) of Morasha in contemporary Ramat Hasharon, where his family eventually settled after making aliyah from Iran in 1949. And a great job he did of that, too.

The mostly posed shots resound with the charming sociocultural resonances of yesteryear Israel, a time when – as per the exhibition moniker – life here was less complicated. Perhaps that is to err on the side of a rose-tinted nostalgia view of how things were here back then. Surely, there were political intrigues and tiffs between communities of various religious and ethnic stripes, not to mention national security issues aplenty. But catching the facial expressions and body language of Yerushalmi’s subjects, one can’t help but smile, and possibly utter a sigh of cozy reflective pleasure.

JUST TAKE a look, for example, at the shot of a couple of boys, probably aged around 11 or 12, looking more than a little proud of themselves as they clasp a soccer ball. They are clearly happy to pose for Yerushalmi who, they must feel, is one of them. This isn’t some interloper making a smash-and-grab foray into foreign climes to capture “the natives” in their natural milieu and hotfoot it back to his own, very different – presumably of loftier socioeconomic standing – patch.

There’s more. And it is all appealing stuff. It is also a priceless testament to a world that began to disintegrate and morph into very different social-climbing times not too long after Yerushalmi moved on to new professional pastures.

The exhibits make for compelling street-level viewing. You don’t get the feeling that Yerushalmi was trying to punch above his own weight. This comes across as more a labor of love and a sincere effort to commit the people and sights of his locale to film for perpetuity’s sake. This is an enchanting no-frills set of visual works. “He didn’t see himself as an artist,” Swissa notes. “And he was self-taught.”

Yerushalmi caught the photography bug from his nature studies teacher at the boarding school on Kibbutz Hukok, near the northwestern corner of the Sea of Galilee, whither he was dent at the age of nine. “He and the other boys, who made aliyah from places like Iran, Iraq, and Morocco, were never accepted by the kibbutz,” says Swissa.

“They were just kids who attended school there and did a few hours of work every day for the kibbutz – the length of the manual labor shifts increased as these students grew up. But they were always treated as outsiders. That was made plain to them.” Hence Yerushalmi’s unwavering focus on Morasha, its inhabitants and, only as a tangential aside, its structural and natural backdrop.

Swissa says that Yerushalmi’s sidelining at Hukok helped to channel the budding documentarist’s efforts exclusively to his home base. “He only took pictures of Morasha, and only of people,” Swissa asserts. “If anyone asked him why he didn’t take pictures of the kibbutz, he’d tell them in no uncertain terms that he wasn’t interested in that.” A photographer spurned, it seems, becomes an unrepentant homing pigeon.

The youngster put everything he could into his newfound love. “He took any job going when he went home from the kibbutz over the weekends,” Swissa explains. That was after, as a 10-year-old, he became fascinated with the aforementioned teacher’s prints of birds and other fauna. “He asked the teacher if he could also do that. When the teacher said yes, he asked how; and the teacher said he needed to get a camera.”

There was no stopping Yerushalmi as he busted a gut to scrape together the requisite 12 liras he needed to procure a pretty rudimentary Yashica camera. We get to see the entry-level equipment as we enter the exhibition area, next to a self-portrait of the adult photographer, who appears to be in the midst of a meditation session.

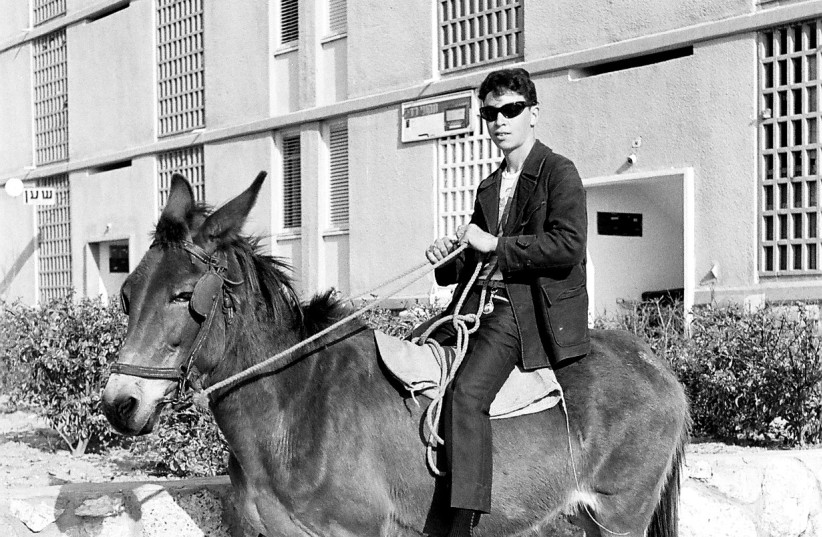

THE ISRAEL I first visited in the early 1970s still resonated with the rippling sensibilities and aesthetics of the socioeconomic and cultural dynamics of Yerushalmi’s decade and a half of restless documentary work. Characters like the three teenagers insouciantly huddled together on a clearly DIY motorbike-cum-car, with a diminutive structure in the background that may have been a neighborhood snack store, ring a distant bell. And there are shots with figures posing on bicycles, next to or inside cars, and on horses.

One in particular shows a bunch of families crowded around a dinner table outdoors. “No one there had a living room large enough to accommodate so many people,” Swissa laughs. You get the zeitgeist picture, literally.

There is the sense of a close-knit community, living on the margins of evolving predominantly Ashkenazi mainstream Israeli society. This is a delightful window into a world long gone.

In his exhibition catalog notes, Sabag cites celebrated Jewish American writer and filmmaker Susan Sontag, who encapsulates the temporal conundrum that is core to the endeavor of all photographers. “All photographs are memento mori. To take a photograph is to participate in another person’s (or thing’s) mortality, vulnerability, and mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs attest to time’s relentless melt.”

Time has certainly marched on inexorably since Yerushalmi toted his camera around Morasha. Which makes his vast oeuvre, and the prints Swissa selected for “La Fête Naïve,” all the more precious.

Any portrait photographer will declare that you need to get to know your sitters before you start snapping away. It is not just about committing aesthetics to print or, in the digital era, on-screen folders, getting the lighting right, or choosing a suitable location. If you really want to convey something of the subject’s essence to the viewer, you have to get a handle on what makes them tick. Yerushalmi had been there and done that in the most natural way possible. He knew the folks in Morasha. They were his neighbors, his pals, the people he’d see on a daily basis.

Swissa puts Yerushalmi’s efforts in cold, hard wherewithal perspective. “He was obsessed with taking photos of Morasha and the people there,” he says. He may have put his heart and soul into capturing life in his own beloved backyard, but he couldn’t just merrily snap away. There were costs to be met.

“He took a lot of trial pictures, you know, in a mirror and that sort of thing. He taught himself. But it wasn’t like today, when you can take as many photos as you want on your cellphone and your digital camera. You had to buy the film and get it developed and printed. That cost a lot.”

BUT YERUSHALMI was hell-bent on mastering the craft, committing the people around him and the spirit of his time to black-and-white imagery. And now, at long last, we have the opportunity to get a glimpse of the man’s deft and loving glimpses of the world in which he grew up.

Romance and adventure were also part and parcel of the Morasha dynamic back in the 1960s and ’70s. “The real temple there was the cinema, the Orion movie theater,” says Swissa. There is a fetching shot in the show of a young lass, decked out in her finest summer frock, on the steps of the local movie sanctuary. “That was a special place for the people there. Look, they have a proper ticket office with a grille and everything.”

The locals were not only happy to have Yerushalmi photograph them, they also wanted him to catch them at their best. Kids and adults appear in their class-A duds in many of the shots. That, according to Swissa, may simply have been down to the fact that Yerushalmi caught them on Shabbat. But the desire to project an image, to present themselves with their best foot forward, is a leitmotif of the spread. One young man poses as a swimsuit-clad hunk, while another appears to be trying to win an Elvis lookalike competition. “Look at him, Swissa smiles, “with his carefully coiffed hair.”

Elvis is, apparently, an important case in point. “Yitzhak is crazy about Elvis Presley,” says the curator. “He has 4,000 records of Elvis.” While Presley may have been the supreme king of rock and roll and churned out quite a few discs during his 20-year career, he didn’t get anywhere near that astronomical figure of releases.

But the point is well taken and succinctly illustrated by a photo of Elvis in one of his 20-plus big screen roles. “Yerushalmi would take photos of the screen at the cinema when they showed Elvis’s movies,” Swissa chuckles. The result, although far from technically flawless – taking a good shot of a film scene must have been tricky, particularly in a dimly lit movie house – the image gets the adulatory message across.

One print in the exhibition stopped me in my tracks. After happily viewing the mostly smiling faces in the two display areas, I suddenly saw a print of a tree, some flora, and an empty chair. “Yes, I guess he started to become a bit of an artist,” Swissa concedes when he catches my surprise.

As befitting the Photopoetics designation, the black-and-whites are interspersed by some stirring poetic offerings, courtesy of Israel Prize laureate Erez Biton, writer, educator, and researcher Zmira Poran-Zion and poet, filmmaker, and activist Vicky Shiran. In one of his contributions, The Cemetery in Lod, octogenarian Algerian-born Biton portrays the town in which his family settled after making aliyah, the kaleidoscope of characters that peopled it, and the trials and tribulations they endured over the years.

Meanwhile, Shiran deftly paints a plaintive picture of the sociopolitical and socioeconomic conditions in the poorer quarters of southern Tel Aviv, where she lived with her family and worked as a teenager to help keep the family afloat. The poems provide a moving textual counterweight to the photographs.

La Fête Naïve is the result of research Swissa conducted on anonymous photographers outside the main focus of market interest. Expect more where that lot came from. ❖

For more information: musrara.co.il/en/