On January 28, The Jerusalem Post published the article “Keeping World Jewry in Mind” by Shira and Jay Ruderman. The authors take the Israeli government and people to task for not participating in International Holocaust Remembrance Day. Israel, they argue, is “disconnected from the daily experience of Jews around the world, for whom antisemitism is a daily struggle.”

I want to first address the presumed lack of will to acknowledge “the disaster that befell the Jewish people” – that is, the Holocaust. Although Holocaust Remembrance Day is mentioned, we must highlight not only this sacred and firmly established date but the extent of its commemoration in Israel.

The first Holocaust Remembrance Day took place on December 28, 1949. Ashes and bones were brought from the Flossenburg concentration camp and buried in Jerusalem. The Knesset eventually chose the date of 27 Nissan, a week after Passover and eight days before Independence Day, and on April 8, 1959, it officially instituted the Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Day Law.

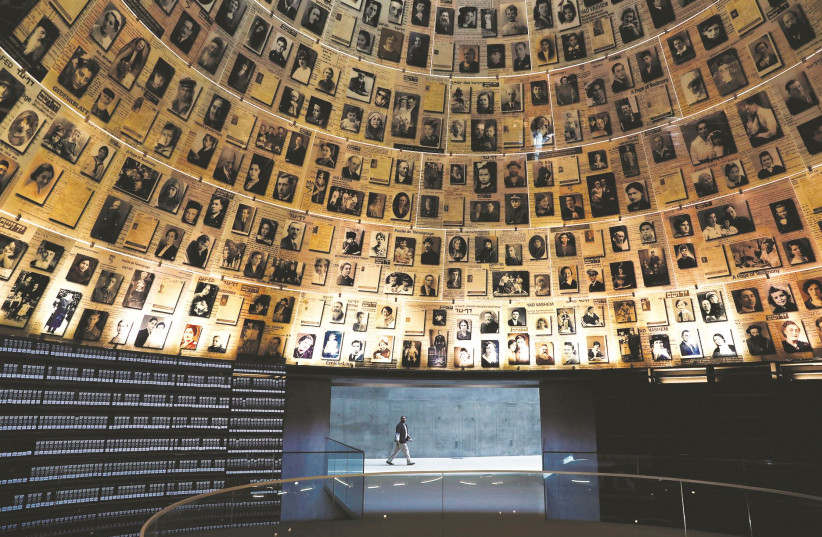

How is this day celebrated in Israel? Opening the commemorative ceremony at Yad Vashem, the president, prime minister and chief rabbis speak, and an additional six torchbearers, survivors and their relatives light an eternal flame and narrate their stories for viewers around the world. Ceremonies are conducted in every municipality, in schools and by the youth. There are film screenings and talks; on the radio, lectures and survivor testimonies.

Flags are flown at half-mast. A siren rings out countrywide, and the nation of Israel stands for two minutes of silence. On television, you can watch either a Holocaust film, documentary or Yizkor candle. Holocaust Remembrance Day, for 64 years, has been a national memorial day; it is overpowering and encompassing.

No one has to remind Israelis to remember the Holocaust. It is an important chapter in the school curriculum; high-school students, until the coronavirus pandemic, traveled to Poland with their classes to witness for themselves the scenes of tragedy. A trip to Yad Vashem is made in middle school, high school, the army and in many professional capacities.

In addition, the Holocaust hovers like a specter behind governmental decisions to protect Israeli lives and fulfill the promise, “Never Again.” On the anniversary of the Wannsee Conference on January 20, 2022, Prime Minister Naftali Bennett acknowledged the tremendous responsibility he feels for ensuring Israel’s safety. “I don’t forget that at the moment of truth… no one (except for rare exceptions) cared about the fate of our people. The world did not lift a finger,” he wrote in a Facebook post.

International Holocaust Remembrance Day was born on November 1, 2005, when the United Nations passed a resolution commemorating January 27, the liberation of Auschwitz. This is a wonderful initiative, and the UN should be lauded; many Israelis did participate in online commemorations and lectures.

On the other hand, this date does not approximate, either in its history or forms of commemoration, the national date so long held in Israel. The emotional impact of Holocaust Remembrance Day is compounded by its proximity to Remembrance Day for the Fallen of Israel’s Wars and Victims of Terrorism, by which most Israelis have been touched with personal loss, connecting the tragedies of the past to those of the present. It is a symbolic truth that Yad Vashem and Mount Herzl share the same location, the Mountain of Remembrance.

This brings me to the accusation that Israelis, who have become “immersed in problems of their own,” are disconnected from the fear and helplessness that comes from living with antisemitism. Israelis, according to the Rudermans, cannot identify with the lack of security that comes from feeling wary about “wearing a kippah” or “hesitating about taking the kids to a gym class at the community center.”

The recent events in Colleyville, Texas, and the rise in attacks on Jews is frightening, but to argue that Israelis are disconnected from antisemitism borders on the absurd.

Israel is a country that is threatened with extermination on a regular basis. Iran’s efforts to achieve a nuclear weapon are accompanied by calls to wipe Israel off the map. On every border there are factions who wait for opportunities to attack with missiles, drones and even arson, and they continually breach those borders, hoping to infiltrate and murder any Jew they can.

These events are not only organized by Hamas, Hezbollah and Islamic Jihad on the other side of the border. Civilians in Israel are attacked with guns, knives and cars at bus stops, train stations and supermarkets.

I think about Ori Ansbacher, a 19-year-old who went for a walk in the Jerusalem Forest near the youth center where she volunteered on February 7, 2019. There she encountered Arafat Irfaiya, whose family is affiliated with Hamas. He brutally raped and murdered her. His reason for doing so was to become a “martyr” by murdering a Jew. Those were his words, “a Jew.”

In the last few weeks, how many Jews abroad have heard of Yehuda Dimentman, a 25-year-old student and father gunned down by terrorists in December? Or Eli Kay, a 26-year-old immigrant from South Africa gunned down on his way to work in Jerusalem’s Old City in November?

I think of all the people who have been stabbed or run over within a five-kilometer radius of my house; the list is long. My son, now 20, was in an elementary-school class with a list of bereaved families: One boy lost his 15-year-old brother in the murder of students in Merkaz Harav Yeshiva in 2008; another had a 26-year-old sister run over and killed by a Palestinian at a bus stop in 2009.

By the time my son graduated eighth grade, he knew more victims of terrorism than most people meet in a lifetime. Last Jerusalem Day, when Hamas shot rockets at Jerusalem as youth packed the Western Wall Plaza for dancing and singing, we heard the sirens and the thud of rockets exploding. Both of my daughters who were there, ages 17 and 15, found a place next to a wall to lie down while the rockets hit.

Every day these girls travel to school in Jerusalem. During the Arab riots this past May, they had to be escorted to school by Border Police officers in full riot gear to protect them from attack from the adjacent Arab village.

This list is a seriously abbreviated example of my experience in the 16 years since I have lived here, and I can only imagine what children who live near the southern border experience.

What are these acts of terrorism based on if not antisemitism and the desire to kill, maim or eradicate every single Jew in Israel? In addition, when Israel acts in self-defense, the voices from abroad, even Jewish ones, offer criticism and disappointment. The fight against antisemitism and terrorism has been conflated with anti-Israel propaganda, the newest form of the oldest hatred.

But to view the murder of innocent Israelis (read here: Jews) as anything other than antisemitism is to accept the myth with roots in every stereotype and libel. Eminent Holocaust historian Yehuda Bauer argues that wanting to destroy the Jewish state because it is Jewish is by definition antisemitic. Hezbollah television station Al-Manar itself exposed the false claims of anti-Zionists: “There is no such thing as Zionism. There is only Judaism.”

Israel is an imperfect place, a place midway to its great destiny, but it cannot be accused of not honoring the six million or of being untouched by antisemitism. The experience of antisemitism causes anger and sadness, but what I don’t see is fear and helplessness.

Our incredible Israeli youth accept this rabid and murderous antisemitism, learn to protect themselves, serve in the army and volunteer with victims of terrorism. People here build schools, develop educational programs and dedicate parks to honor those murdered. And so, perhaps, we don’t identify with that kind of fear.

I believe that world Jewry has a lot to learn from Israel about Jewish pride and strength that rises from Jewish nationhood. Perhaps these are lines along which we should reach out to world Jewry to help fight against hostility and hatred – to know our history, to embrace identity.

Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook, first chief rabbi of pre-state Israel, said the righteous “do not complain of the dark, but increase the light... they do not complain of ignorance, but increase wisdom.” If all Jews, in Israel and abroad, work together, we can prevail.

The writer is a faculty member in Achva Academic College’s English Department and an MA student in the University of Haifa’s Holocaust Studies Program.