The Emergency Regulations Law in Judea and Samaria is expected to be brought to the Knesset plenum for another vote in the coming days, after being voted down in the Knesset plenum for the first time in over five decades. This rather standard legislation, which has been passed without question every five years since 1967, failed to pass a first reading last week, due to a perfect storm of political and ideological arm wrestling: Of the Knesset’s 120 parliamentarians, 52 MKs voted in favor, 58 opposed.

The emergency regulations apply Israeli law to citizens living in Judea and Samaria, and mainly concern the powers of Israel’s judiciary and executive branches regarding Israelis who have committed crimes in Judea and Samaria, including areas under Palestinian Authority jurisdiction. These regulations make it possible for Israel to carry out orders and enforce punishments on Israeli citizens, and create a framework for legal cooperation between Israel and the relevant arms of the Palestinian Authority.

If the emergency regulations are allowed to expire at the end of this month, things may become complicated for law enforcement authorities, as well as for the residents of Judea and Samaria. In the opinion of Israel’s deputy attorney general, “this will create legal and practical difficulties in conducting complex or joint investigations, which is a significant factor and a vital element of the powers vested in the Military Governor, impacting governance of the area and maintenance of public order and security.”

But the real story here is not the renewal of stop-gap measures that create an illusion of normalcy. The heart of the matter is, or should be, the ongoing failure of Israeli governments to formulate policy, to articulate a national vision and to demonstrate governance.

Timidity

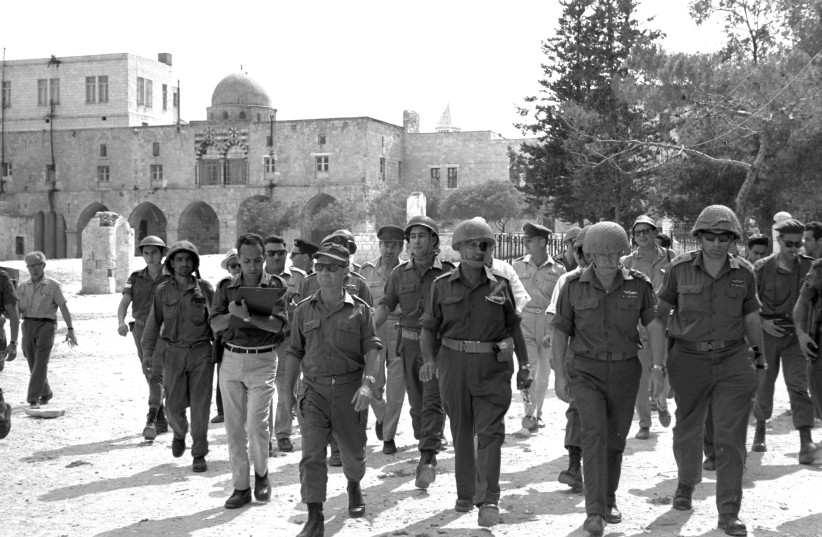

Since 1967, the only thing that has prevented Israeli governments from applying Israeli law in Judea and Samaria is their own reticence – actually, their timidity. In the aftermath of the Six Day War, in which Egypt, Syria and Jordan invaded Israel in a combined military action, Israel attained control of the areas of Gaza, the Golan, Judea and Samaria.

Immediately, perhaps inexplicably but most certainly unfortunately, Israel chose – voluntarily – to establish a temporary military administration to govern the local population, until a negotiated resolution could be achieved. Since neither Jordan nor Egypt had acquired recognized sovereign powers in the areas, Judea and Samaria could not be formally defined as occupied territories; nonetheless, Israel committed itself to act in accordance with the relevant norms of international law, pending a negotiated settlement – without officially acknowledging the formal applicability of the Fourth Geneva Convention to these areas. This temporary, neither-fish-nor-fowl situation has endured ever since and the emergency regulations implemented at the time continue to prop up the legal construct that continue to serve all the parties concerned.

This has led to a chaotic reality that harms the security and quality of life of the residents of Judea and Samaria, Jews and Arabs alike, and the security of Israel as a whole.

These regulations deal mainly with criminal law and civil rights, and while the various technical clauses reveal the official policy of Israel to criminality in Judea and Samaria, what is not included may be even more telling: In completely ignoring the issues of proprietary rights – real estate law and ownership – they lay bare the failure of successive Israeli governments to protect the basic rights of the state and its citizens.

Proprietary rights in Judea and Samaria remain under the Jordanian and Ottoman systems, and these laws are outdated, ineffective and in some cases even antisemitic. Even worse, perhaps, is the selective manner in which these laws are enforced by the Israeli judicial and military systems. Selective enforcement of outrageously outdated laws has enabled – and continues to enable – the Palestinian Authority to exploit the Israeli system, to annex vast areas of Judea and Samaria, to redraw the map and to lead the entire region toward violent confrontation. Continued reliance on emergency legislation may be the lesser of evils, but it most certainly is not the solution.

The writer is director of the International Division of Regavim, a public Israeli non-government watchdog and lobbying group dedicated to the protection of Israel’s land resources and the preservation of Israeli sovereignty.