This year’s Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Day was a particularly poignant historical moment of remembrance and reminder, bearing witness, learning and acting upon the universal lessons of history and the Holocaust.

I write this in the aftermath of the 90th anniversary of the establishment, in 1933 by the Democratic Government of Germany, of the infamous Dachau concentration camp – the forerunner of the deportation to Dachau of thousands during Kristallnacht. This reminds us that antisemitism is toxic to democracy, an assault on our common humanity and as we’ve learned only too painfully and too well, while it begins with Jews, it doesn’t end with Jews.

I write also in the aftermath of the oft-ignored if it is even known at all 81st anniversary of the Wannsee Conference of January 20, 1942, convened by the Nazi leadership to address “The Final Solution to the Jewish Question” – the blueprint for the annihilation of European Jewry – which was met by the indifference and inaction of the international bystander community. In January 1942, 80% of the European Jewry was still alive. A year later, 80% of them had been murdered.

I write also on the 80th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, the most heroic Jewish and civilian uprising during the Holocaust – which was itself preceded by the deportation of 300,000 Jews from the Warsaw Ghetto to the death camp Treblinka in 1942 and the death by starvation and disease of another 100,000. There is a straight line between Wannsee and Warsaw; between the indifference of one and the courage of the other.

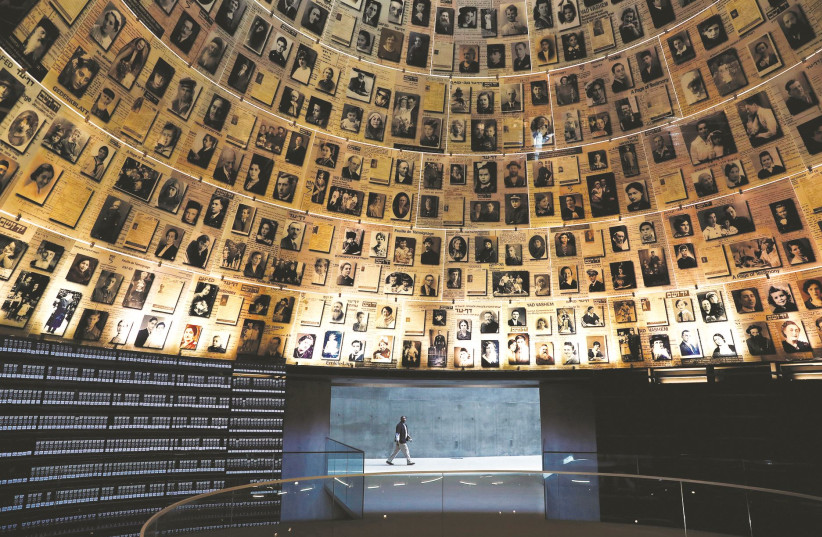

I write also following a visit to Yad Vashem, including a visit to the Valley of the Destroyed Communities, such as the destroyed Jewish community of Lithuania, which included close to 70 members of my own family, where there are no graves or tombstones. The Nazis and their collaborators sought not only to exterminate the Jews but also to extinguish the memory of every Jew.

AS I made my way through the Valley of the Destroyed Communities, I suddenly heard the Partisan song “Zog nit keyn mol az du geyst dem letsn veg” (never say you are traveling the last road), which my mother of blessed memory would sing to me as a child and which became for me an anthem of resilience and hope for the Jewish people. It resonates particularly profoundly as we prepare to mark Independence Day, against the backdrop of President Herzog’s powerful address, saying, “We are one people bound by history, hope and faith.”

I write also amidst the international drumbeat of evil – reflected and represented in the unprovoked and criminal Russian invasion and aggression in Ukraine, underpinned by war crimes, crimes against humanity and incitement to genocide, which is a stand-alone crime under the Genocide Convention.

There are also the increasing assaults by China on the rules-based international order, including mass atrocities targeting the Uighurs, which are constitutive of acts of genocide; the Iranian regime’s brutal and massive repression of the Iranian people’s “women, life, freedom” human rights revolution; and the mass atrocities targeting the Rohingya, Afghans and Ethiopians.

In addition, there is increasing imprisonment of human rights defenders, like Russian patriot and human rights hero Vladimir Kara-Murza, the embodiment of the struggle for freedom and a critic of the invasion of Ukraine who was convicted of high treason and sentenced this week to 25 years in prison for telling the truth, a re-enactment of the Stalinist dictum of “give us the person and we will find the crime.”

And I write also amidst an unprecedented global resurgence of antisemitic acts, incitement and terror – of antisemitism as the oldest, longest, most enduring and most dangerous of hatreds. It is a virus that mutates and metastasizes over time but is grounded in one foundational, historical, generic, antisemitic, conspiratorial trope: that Jews, the Jewish people and Israel are the enemy of all that is good and the embodiment of all that is evil, regardless of what moment in time we are experiencing or living in.

What have we learned the last 80 years?

AND SO at this important historical inflection moment, we should ask ourselves what have we learned over the last 80 years and more importantly, what must we do – which lessons and actions include the following:

• The danger of forgetting and the imperative of remembrance – of the Holocaust as Nobel Peace Laureate Professor Elie Wiesel put it, “as a war against the Jews in which all victims were Jews, but all Jews were targeted victims” – of horrors too terrible to be believed but not too terrible to have happened. The demonization and dehumanization of the Jew as prologue and justification for their mass murder.

• The danger of regarding the mass murder of six million Jews – 1.5 million of whom were children – and millions of non-Jews – as abstract statistics; for as we say at these moments of remembrance, onto each person, there is a name; each person is an identity; each person is a universe: reminding us of the Talmudic idiom that if you save a single life, it is as if you have saved an entire universe.

• The danger of antisemitism – the oldest, longest, most enduring and most lethal of hatreds. If the Holocaust is a paradigm for radical evil, antisemitism is a paradigm for radical hate that must be combated.

• The dangers of Holocaust denial and distortion – of the assault on truth and memory and the whitewashing of the worst crimes in history and our responsibility to unmask the bearers of false witness.

• The danger of state-sanctioned incitement to hate and genocide – the Holocaust, as the Supreme Court of Canada put it, “did not begin in the gas chambers, it began with words.”

• The danger of silence in the face of evil – where silence incentivizes the oppressor, never helping the victim – and our responsibility is always to protest against injustice.

• The dangers of indifference and inaction in the face of mass atrocity and genocide. What makes the Holocaust and the genocide of the Tutsis in Rwanda so horrific are not only the horrors themselves. What makes them so horrific is that they were preventable.

Nobody could say we did not know. Just as today, with regard to mass atrocities being perpetrated against the Uighurs, the Rohingya and the Ukrainians, nobody can say we do not know. We know and we must act.

• The Trahison des Clercs (the betrayal of the elites) – doctors, scientists, judges, lawyers, religious leaders, educators, engineers and architects. Nuremberg crimes were the crimes of Nuremberg elites. Our responsibility, therefore, is always to speak truth to power.

• The danger of cultures of impunity and the corresponding responsibility to bring war criminals to justice. There must be no sanctuary for hate, no refuge for bigotry and no immunity for these enemies of humankind.

• The danger of the vulnerability of the powerless and the powerlessness of the vulnerable. The responsibility to give voice to the voiceless and to empower the powerless. In a word, the test of a just society is how it treats its most vulnerable among them.

And so, the abiding and enduring lesson is that we are each, wherever we are, the guarantors of each other’s destiny. May this day be not only an act of remembrance, which it is, but a remembrance to act, which it must be, on behalf of our common humanity.

The writer is an emeritus professor of law at McGill University, the International Chair of the Raoul Wallenberg Center for Human Rights, a former justice minister and an attorney-general of Canada, a long-time parliamentarian and an international legal counsel to prisoners of conscience. He is Canada’s first Special Envoy for Preserving Holocaust Remembrance and Combating Antisemitism.