I was recently asked a question that so many Jews must be posing themselves right now as the Israel-Hamas War finally comes to an end. With it comes the hope that the tsunami of antisemitism that has overtaken the planet will also end.

How do we move on from here? How do we reconnect with the endless progressive groups that Jews and Jewish institutions supported for many years that so disappointed us following the Hamas attack two years ago. The feminists who chanted for Gaza; the “queers” who shilled for “Palestine”; the Black Lives Matter members who applauded Hamas’s atrocities.

My answer is: We don’t.

Why should we? These groups have done astoundingly well by Jewish allies and donors, yet failed Jews spectacularly in our hour of greatest need. And as these hours come to a merciful close, Jews wondering how to rebuild bridges and reestablish alliances must accept that they do not actually need to.

Judaism as an alternative to progressive movements

There are wholly viable alternatives to these movements at their disposal: Jews and Judaism itself.

Before October 7, a coercive sense of white guilt propelled many Jews and Jewish institutions into funding the identity movements that turned so violently against us. This patronage must stop.

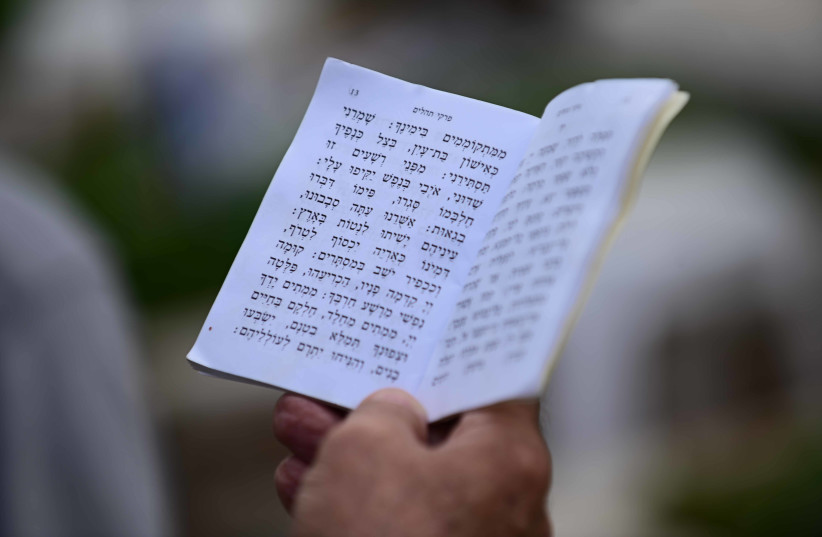

Instead, we must turn our money and attention inward. I certainly have. Like so many Jews today, our collective sense of peril has left me feeling more Jewish than ever. It is into this heightened sense of Judaism that we must lean when considering bridge building or reparative work ahead.

On a purely philanthropic level, efforts to “go Jewish” are already taking root. In December 2023 – as anti-Israel protests exploded at college campuses worldwide – Canadian real estate billionaire Sylvan Adams gave $100 million to Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in Beersheba. It was one of the largest gifts of its kind, setting a precedent that other donors followed.

This past May, Jonathan Gray, president of investment firm Blackstone, donated $125 million to Tel Aviv University.

This is merely the beginning. At a time of rising assimilation and antisemitism, we need all the Jews we can muster right now. And they are there to be found because built into Judaism itself are the queers and Blacks and Latins and Asians and feminists and social justice fanatics that we’ve so blindly supported outside of our community all these years. And guess what – they’re all Jews too. We don’t need to look beyond Judaism for diversity or intersectionality – we have plenty of it already.

Post-October 7, we no longer need to virtue signal our support for folks who don’t share our core values – and are often literally calling for our extermination.

We can and must support our own.

You want identity and intersectionality – guess what? There is plenty of it right here with us Jews. Recent estimates, for instance, put the number of Jews-of-color, like myself, at roughly 15% of the entire US Jewish population; that’s over a million people.

Today, we must begin to expand the definition of what it means to be part of us.

Us Jews: It means claiming the diversity that is everywhere within Judaism today. Why waste our time and cash on #blm when there are plenty of African-American Jews who share our passions and values? The same applies to Hispanic Jews and Asian Jews, queer Jews, and radical feminist Jews.

American Jews still committed to uplifting and elevating marginalized voices: Go uplift and elevate marginalized Jewish voices. The folks who have been standing in the background, quieter than most, darker than most, poorer than most, but are very much still Jews. Uplift their voices – rather than bogus identity causes that have so effortlessly sent us to the wolves. Causes we, ultimately, often had so little in common with in the first place.

We can and should retain our commitment to inclusive principles – which are noble, just, Jewish – but apply them to Jews and Jewish environments. We must seek connection with Jews who may not look or speak like us, and ensure that Jewish institutions no longer merely reflect outdated, Eurocentric views. We must make concrete efforts to get more “seats at the table,” but make them Jewish seats at a Jewish table.

In my case, as the son of an Ashkenazi mother and African-American father, stepping into a larger Jewish world that has often refused to acknowledge me has been scary, but also liberating, revolutionary, and an embrace of an authentic me I never knew existed. And I’ve only just begun.

The writer is an adjunct fellow at The Tel Aviv Institute and a former editor and columnist for the New York Post.