The reconstruction of Gaza will take a long time. The first task is to provide suitable temporary housing for Gaza’s more than two million residents. Infrastructure for water, sanitation, electricity, roads, and internet connection must be part of the immediate construction. If we want to imagine a future in which the people of Gaza decide to live in peace with Israel, these are the first steps that need to be taken, before considering the political developments that must happen – mainly recognizing the Palestinians’ right to freedom and self-determination.

Gaza has been destroyed by Israel, and more than 70,000 Gazans have been killed. The people of Gaza will never forget and it will be difficult to forgive. But most Gazans I have spoken to have also said that while Israel did the destruction and the killing, they hold Hamas responsible. The public sentiment they describe is that the people of Gaza never want to see another person from Hamas in their lives. Many of them have said that they only want to live in peace and to never see war again. This is a new starting point for Gazans to build a future that provides hope for freedom and a much better life.

In US President Donald Trump’s 20-point plan to end the Israel-Hamas War, point 18 calls for the establishment of an interfaith/dialogue process based on tolerance and peaceful coexistence with the goal of changing the patterns of thinking and the narratives of Palestinians and Israelis by emphasizing the benefits that peace can bring.

This is a crucial point in the plan. It is important that the suggested changes and reforms in education take place on both sides – in Israel and in Palestine. I will start with Gaza, simply because the influence of the United States and the Board of Peace will be so profound in Gaza that it is in Gaza where the changes can take place first. The success of these changes in Gaza will impact changes in the West Bank, and they must impact education in Israel as well.

Educational reform

The core reform in education in Gaza has to be based on the 4 D’s: Demilitarization, Deradicalization, Democratization, and Development. The process must be designed to be acceptable to Palestinians, donors, and international guarantors without triggering fears of imposed “reeducation.”

The framework should be a civilian-led approach to rebuilding and reforming Gaza’s education system following the cessation of hostilities. Its objective is to restore normal life, build civic capacity, and foster human development, while preventing the education system from being instrumentalized by armed factions, political factions, or external security agendas.

The framework should be grounded in international experience from post-conflict societies, including Northern Ireland, Bosnia, and Colombia, and even from post-World War II situations such as Germany and Japan, and in reconciliation processes.

The guiding principles

It is important to remember that education is a stabilizing institution, not a political weapon. The reformed educational system must have Palestinian ownership with international support. Schools must be spaces that are civilian, neutral, and protected. Schools have to be designated as weapons-free civilian zones, including the removal of armed symbolism from educational materials and premises.

To provide legitimacy for the system, the education authority must be under the control of the Palestinian transitional governance structure. The Americans and others will insist on a clear program of deradicalization. For that to occur, there must be reduced incentives for violence, which means the end of the war must be genuine and Israel must cease its control and remove the obstacles it places on life for the Gazans.

There is no other conflict zone exactly like Israel-Palestine, but there are lessons that can be learned and adapted from other conflict zones. For example, in Northern Ireland, deradicalization was achieved through skills-building and political agency, not enforced narratives. Efforts were made to shift from indoctrination to critical thinking, media literacy, evidence-based reasoning, and the elimination of the glorification of violence. They specialized in teacher training with an emphasis on trauma-aware pedagogy, facilitating disagreement without violence, teaching nonviolent political participation, and conflict analysis skills.

The most difficult issue to be confronted in Gaza’s new educational system is how to teach about the conflict, the Palestinian people and their struggle for statehood, the failed peace process, Israel and the Jewish people, and the connection of both peoples to the common homeland of Palestine/Israel. The following are some thoughts and lessons learned from my own experience in running a peace education program in Israel and Palestine from 1994-2005.

What Gazans should learn about Palestine and Palestinians

In post-war Gaza, education cannot be asked to carry the impossible burden of erasing pain, history, or national identity. Its task is more modest, and at the same time more profound: to help a shattered society rebuild dignity, knowledge, and agency, while ensuring that the next generation is equipped to pursue Palestinian rights without being trapped in permanent war.

That means teaching Palestine, Palestinian identity, and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict honestly, confidently, and responsibly – not as propaganda and not as enforced “peace” but as education that prepares young people to live, think, and act as citizens.

In post-war Gaza, Palestinian identity should be taught first and foremost as a living culture and society, not only as a victimhood shaped by conflict. Children need to learn who they are before they are asked to understand who they are in conflict with.

Education should root identity in language, history, geography, culture, and community life: the story of Palestinian towns and villages, family histories, agriculture and trade, literature and poetry, music and dance, religious and social pluralism, and the diversity of Palestinian experiences in Gaza, the West Bank, inside Israel, and in the diaspora. This kind of teaching restores pride without hatred. It sends a clear message: Palestinian identity is rich and complete on its own; it does not depend on negating others.

After war, legitimacy comes not from slogans but from rights-based understanding. Palestinian students should be taught the language of human rights, international humanitarian law, self-determination, equality, and civic responsibility.

This helps young people understand that supporting Palestinian rights does not require loyalty to any single faction or method. It also teaches them how to argue for their rights using law, ethics, and evidence, rather than dehumanization or incitement – strengthening Palestinian political credibility rather than weakening it. They should be challenged to understand that the armed struggle for Palestinian freedom has not achieved the desired aim and has left Gaza in ruins.

Teaching the conflict through facts and pluralistic narratives

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict must be taught – but carefully and seriously. First, students should learn a shared factual timeline: the late Ottoman period, the British Mandate, the emergence of two national movements, the 1947-1949 war and refugee crisis, the 1967 war and occupation, the Oslo process, the intifadas, the Gaza Disengagement, blockade, repeated wars, and the most recent devastation. Facts should be presented without slogans, and age-appropriately.

Second, students should be introduced to parallel narratives: the Palestinian narrative of dispossession, occupation, and denied rights; the Israeli Jewish narrative of peoplehood, historical connection, persecution, and security fear; and the often-ignored perspectives of Palestinian citizens of Israel.

The educational goal is not agreement. It is the ability to say: “I understand how the other side sees this – even if I reject their conclusions.” This capacity is what separates political maturity from perpetual conflict.

Teaching resistance, strategy, and consequences

Post-war education must not glorify violence, but it must not lie about history either. Armed struggle, nonviolent resistance, civil disobedience, diplomacy, and international advocacy should all be taught as strategies, each with historical examples, moral debates, legal implications, and consequences. Students should learn to ask: What advances rights? What gains legitimacy? What protects civilians? What leads to durable political gains? This transforms resistance from myth into strategic literacy.

Addressing trauma without turning it into hatred

After massive loss, schools must also become places of emotional repair. Education should include trauma-sensitive practices, grief literacy, and community support skills – helping students process pain without converting it into permanent rage. This is not psychological “softness.” It is social survival.

A clear moral boundary: dignity without incitement

Post-war education must draw firm lines. It must reject dehumanization of Jews or Israelis, religious demonization, glorification of killing and death, conspiracy myths, and denial of historical facts. At the same time, it must protect teaching the Nakba and occupation as lived Palestinian history. Teaching Palestinian rights must be clear and unapologetic. Legitimate criticism of Israeli policies and governments is necessary. This balance is what turns education into a shield for Palestinian dignity rather than a weapon that undermines it.

The purpose of teaching Palestine and the conflict in post-war Gaza is not to produce agreement, forgiveness, or affection. Those cannot be forced and may take many years to occur. The purpose is to produce Palestinians who know who they are, understand their rights, can explain their struggle without hatred, and are capable of choosing a future rather than inheriting a war. That, in the long run, is not a concession. It is a form of national strength.

What should be taught about Jews and Israel?

The focus needs to be on history, not legitimacy battles. Education must separate historical facts from political claims. The following are some main points; I admit they are controversial to most Palestinians, but it is essential to teach them.

Jews are an indigenous people of this land and the region. Jewish presence in the land existed in the ancient biblical era, in the Roman and Byzantine periods, and more. There has been a continuous Jewish presence in the land even if as a minority. Renewed Jewish presence in the land did occur through modern Zionism. What should not be demanded in the educational curricula is an acceptance of Zionism as morally right, the agreement with Israeli policies, and an emotional identification with Jewish narratives. What is required is to understand the existence of Israel and the reality that it is not going to disappear.

We need to be teaching Jewish connection to the land alongside Palestinian connection to the same land, not instead of it. Two peoples have deep, real, historic and religious connections to the same land.

One great example of an attempt at education reform was the textbook developed with parallel narratives by the late Prof. Dan Bar-On and Prof. Sami Adwan: Side by Side: Parallel Histories of Israel-Palestine. More than 20 years ago, in the midst of widespread violence in Israel and Palestine, a group of Israeli and Palestinian teachers gathered to address what, to many people, seemed an unbridgeable gulf between the two societies. Struck by how different the standard Israeli and Palestinian textbook histories of the same events were, they began to explore how a new understanding of history itself might open up different kinds of dialogue in an increasingly hostile climate.

Their goal was to “disarm” the teaching of Middle East history in Israeli and Palestinian classrooms. The result was a riveting and unprecedented “dual narrative” of Israeli and Palestinian history. Side by Side comprises the history of two peoples, in separate narratives set literally side by side, so that readers can track each against the other, noting where they differ and where they correspond.

In Side by Side, the Israeli and Palestinian teachers acknowledged both Jewish historical trauma and Palestinian trauma. Since the time of that work, new traumas have been experienced by both peoples that go far beyond what was experienced in the past 80 years.

Teaching Hebrew as a language of the neighbor, not the enemy, should be done in Gaza and the West Bank, and teaching Arabic to all Israeli Hebrew speakers should be done from grade one. Language breaks myth much faster than lectures.

Gazan students should encounter the voices of Israeli Jews who support peace and acknowledge Palestinian suffering and Palestinian rights. They should also hear the voices of bereaved families from both sides. Gazans should be taught about Israel and Jews in a way that respects Palestinian identity and suffering, teaches truth without humiliation, separates history from politics, and prepares for coexistence, not surrender. The goal is not love. The goal is understanding without hatred.

First steps

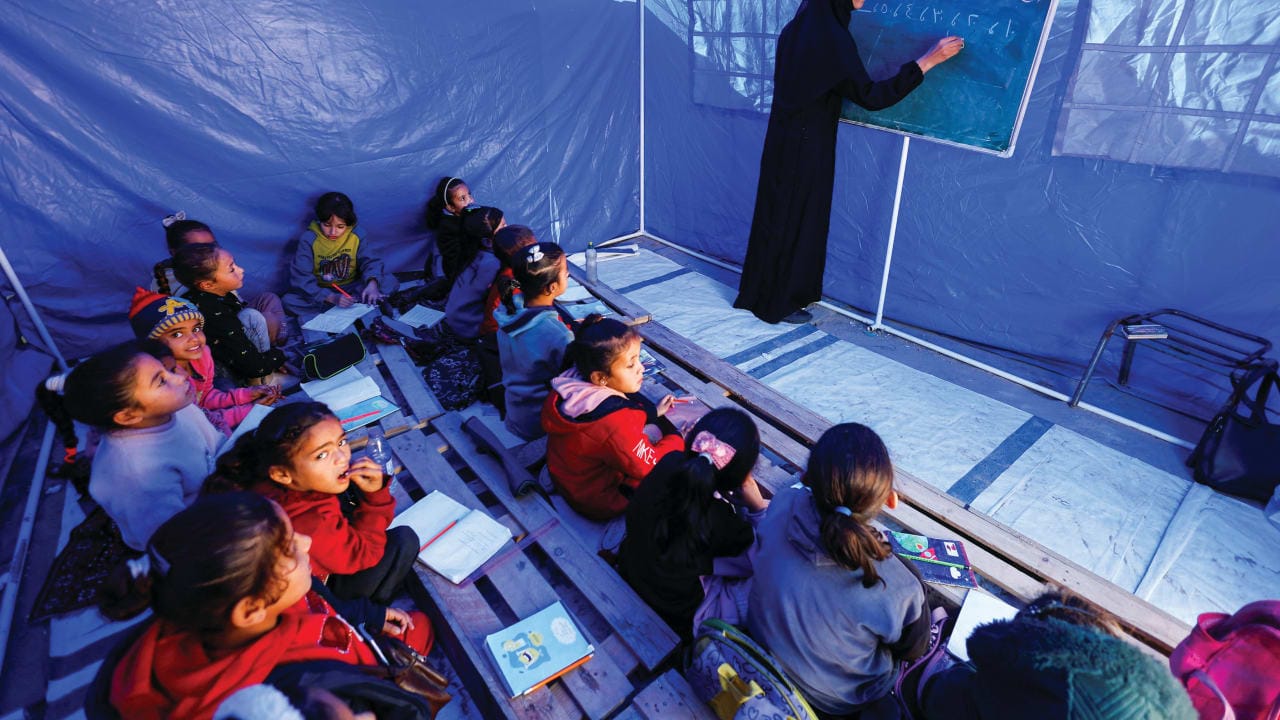

For any of this to happen, it is essential to first restore education as Gaza’s primary human-capital engine. Investments in education must be prioritized. Rebuilding and equipping schools is on par with the provision of temporary housing. Teachers must be hired who are retrained in the new curricula and provided with good salaries to ensure the highest quality in the classrooms.

Special attention needs to be placed on trauma-aware pedagogy. Media literacy and critical thinking are a central core to teaching the post-war generation. Teachers and schools must be insulated from armed groups, political faction patronage, and security/intelligence involvement in the content of the curricula. We must eliminate slogans of “martyrdom” glorification.

It is not necessary to rush with “coexistence projects” that look like normalization until later.

The writer is the Middle East Director of International Communities Organisation and the co-head of the Alliance for Two States.