An exciting new project will see scientists take a closer look than ever before at Earth’s nearest interstellar neighbor to find new worlds, some of which could be able to host life.

Dubbed TOLIMAN, the project is the work of Breakthrough Watch, a project of the Breakthrough Initiatives program founded by Russian-Israeli billionaire Yuri Milner, along with the Australian company Saber Astronautics and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. The project will see a new space telescope launched in order to closely examine the Alpha Centauri system.

The mission’s name is an acronym for Telescope for Orbit Locus Interferometric Monitoring of our Astronomical Neighborhood, but is also derived from the old Arabic name for Alpha Centauri.

The system in question is the closest star system to our own, located just over four light-years away. However, there are some very notable differences. Unlike our own solar system, which only has one star, Alpha Centauri has three, making it a triple star system. Two of these stars – Alpha Centauri A (Rigil Kentaurus) and Alpha Centauri B (Toliman) – are the same type of star as our sun. The third star, Alpha Centauri C (Proxima Centauri), which is the closest of the three to Earth, is a smaller, red dwarf star that is harder to notice.

But what is especially interesting about this star system is the presence of exoplanets, a term that refers to any planet discovered outside of our solar system. While scientists have long theorized that exoplanets exist, only a relative handful – around 5,000 – have definitively been identified throughout the infinite reaches of the cosmos. This is because it can be very difficult to truly spot them, especially since the brightness of stars tends to vastly overwhelm the brightness reflected off these worlds.

But scientists are confident that some planets exist in the Alpha Centauri system. One planet, believed to be a giant planet comparable in size to Neptune, is thought to be orbiting Rigil Kentaurus. It is likely a gas giant, though because it inhabits the habitable zone, its moons could potentially be able to support life, something Breakthrough Initiatives executive director Pete Worden compared to the planet in the 2009 James Cameron film Avatar.

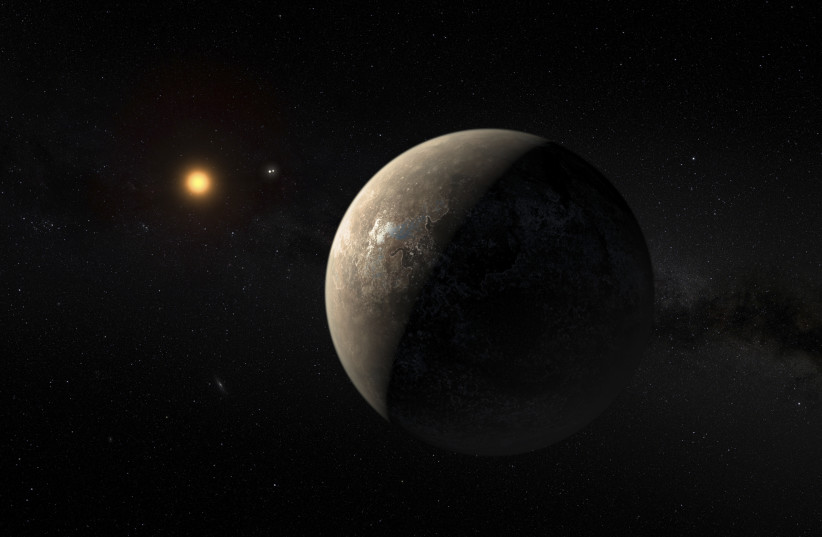

But it is Proxima Centauri that is the most interesting.

WHILE THE existence of the giant planet is still unconfirmed, two exoplanets are confirmed to be orbiting Proxima Centauri: Proxima b and Proxima c. Of the two, the former is close in size to Earth and is in the habitable zone. And as an Earth-sized world in the habitable zone of a red dwarf star, some have drawn comparisons to Superman’s fictional homeworld of Krypton.

Though Proxima b is in the habitable zone, and scientists believe it is a rocky world, there is still so much unknown about it.

But why are we only now looking at our closest interstellar neighbors, whereas other missions have focused on more distant stars?

Part of this has to do with the brightness, which can make observation difficult. As a result, the new TOLIMAN space telescope uses measurements to find the exact position of these stellar bodies and, in turn, deduce their mass, a field of study known as astrometry.

When a planet orbits a star, its own gravity will tug on the star ever so slightly, causing the star to “wobble,” Worden explained. This can help scientists detect the mass and distance of an exoplanet from the star.

“We can’t detect the composition of an exoplanet, but if we determine the mass – like five times of Earth – and we can measure the brightness – and we have a marginal measure for the giant planet – then we can make assumptions about the reflectivity,” he said. “From that, we can deduce the radius and then that way, you can get a mean density. So if it’s a rocky world or water world, you can figure it out.”

But it is unclear if Proxima b can support life.

“Proxima Centauri is a flare star,” Worden explained. “Every few days, it has an explosion – it might brighten 100 times. It was thought that these would have blown the atmosphere of a planet away.”

But we don’t know for sure, and it is still worth looking at our closest neighbor in space.

The mission is tentatively slated to be launched in two years and will spend four to six years observing Alpha Centauri. Information gleaned from this observation as well as through future advancements in telescopes could eventually lead to atmospheric analyses, such as whether the planet could support life.

Further, this could also determine if the planet was an ideal candidate for another Breakthrough Initiatives program: Breakthrough Starshot, a mission that would see specially designed spacecraft head to Alpha Centauri and send a message back. Though this journey would take over 20 years and would require traveling at around 20% the speed of light, the research into this program seems promising so far.

But as for Worden and Breakthrough Watch, they are already looking into the future.

“There’s another star system further away called 61 Cygni,” he explained. “This is a binary star system: it has two stars similar to the Sun that might be able to support life. We want to look there and see what we can find.”