Role of the media in Israel’s national security psychological crisis - opinion

Israel’s media may be eroding the psychological resilience that underpins its national security.

Israel’s media may be eroding the psychological resilience that underpins its national security.

One thing is for certain: The moment President Trump steps out of the White House, even the best deal will unravel.

As Ramadan begins, Israel takes a cautious approach, managing security without escalating tensions, hoping for a month of prayer and peace.

The extensive and expanding Iranian ballistic missile arsenal is today’s clear and present danger – as is the funding for Tehran’s network of terror proxies.

If we do not cleanse Israel of the Qatari parasite, we will experience much greater disasters than the October 7 massacre.

If the Islamic Republic can weather the blows of the US military and merely remain standing at the end of a Trump presidency, it believes time will be on its side.

Terrorism isn’t just a security threat; it’s a political tool exploited by actors who profit from instability.

Israel has the chance to turn national trauma into national growth and emerge more resilient than ever.

Two female soldiers were attacked in Bnei Brak; if we believe in Torah and unity, Jew-on-Jew violence can never be tolerated.

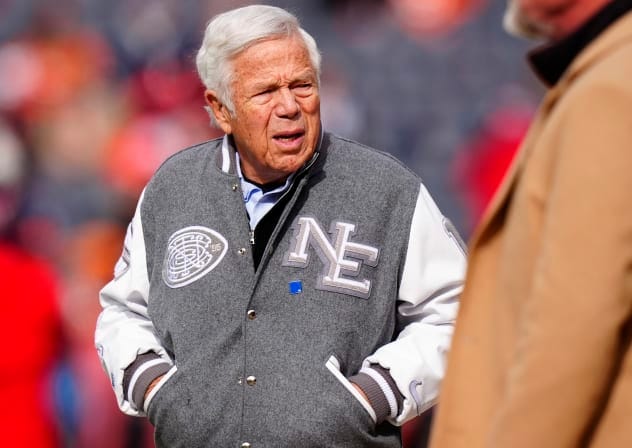

A Super Bowl ad meant to fight Jew-hatred instead showed weakness, missing the moment for true Jewish strength.

The behind-the-scenes journey from draft to deal raises uncomfortable questions about whom the UN truly serves, and for what purpose.