The long-unknown identity of a 19th-century vampire has finally been revealed, thanks to the use of some new, cutting-edge technology.

In 1990, the body of an unknown man was dug up in Griswold, Connecticut, and it was clear to those who discovered him that something about him was unusual, due to the way in which he was buried.

The man had been dug up from his grave several years after his death and then re-buried, this time with his head and limbs piled on top of his ribcage, forming the shape of a cross. This unusual burial technique was believed at the time to prevent vampires from rising from their graves and drinking the blood of the living.

For almost 30 years after his discovery, the identity of this man remained a mystery, and the question as to why he had been buried in this unusual way continued to go unanswered. But now, the latest advanced laboratory and bioinformatic DNA analyses have been performed, and the answers are finally clear. The unknown man is John Barber and he died of tuberculosis.

In the 19th century, as the deadly Tuberculosis disease spread across the six states that make up New England - Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont - a ghastly rumor came with it. The families of those affected by the disease began to attribute blame to the undead, saying that those who perished from the disease would return from the afterlife to prey upon their families.

And so, in a time before germ theory had been discovered, when people did not believe that an earthly cause could be attributed to such a disease, New Englanders took matters into their own hands.

Villagers would dig up the bodies of the recently deceased, exhuming them and reassembling them into the shape of the cross. In some cases, they would remove the internal organs from the body and burn them.

According to a 2019 interview given to history.com by retired Connecticut state archeologist Nicholas Bellatoni, "consumptives lost weight, coughed up blood, their skin turned ashen and sometimes died a slow death—almost as if something was 'sucking the life' out of them."

And with symptoms such as jaundice and red eyes on top of all the others mentioned above, it's easy to understand how frightened villagers, with none of the scientific or medical knowledge that we have today, would have turned to tales of the undead for an explanation.

Enter John Barber.

How did scientists discover Barber's identity?

After Barber's body was initially discovered in 1990, it wasn't until 2019 that a team of forensic scientists from Parabon NanoLabs, a DNA technology company based in Virginia, began working with the Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory (AFDIL) in Delaware in an attempt to discover his identity.

The initial analysis carried out by the forensic team in 2019 had already linked the unidentified body to the possible surname "Barber," and a search of historical records had led to an obituary for another individual buried in the same cemetery that mentioned a man named John Barber, but no other records had been discovered.

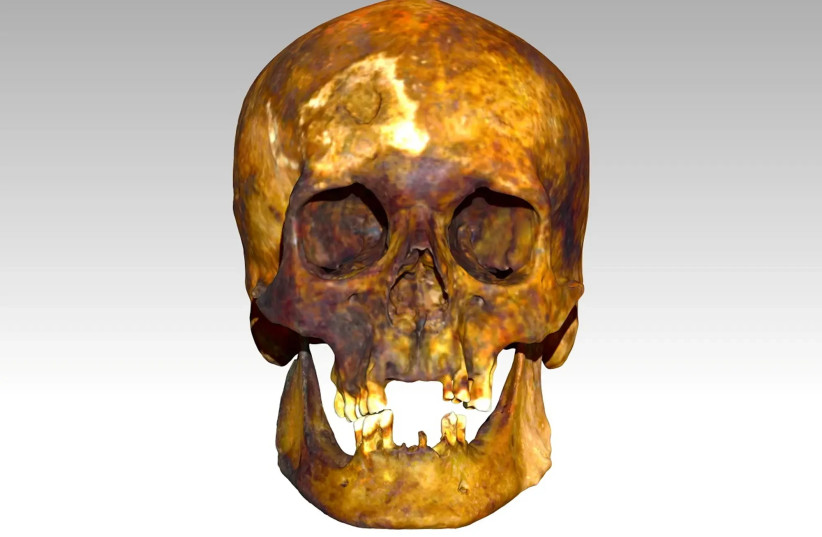

The new study, then, aimed to find an answer to the question of whether or not this man, known then as just JB55 (the initials and age marked out on his coffin), was in fact the same John Barber mentioned in the records. And, if he was in fact, the same person, what did he look like?

After testing various methods of DNA analysis, including shotgun sequencing, targeting the whole human genome, and targeting 850,000 custom SNPs, the method found to be the most cost-effective was that of targeting the whole genome.

In traditional genome sequencing work, the goal is to sequence each piece of the human genome 30 times. However, due to the difficulty of analyzing the DNA of old bones, each sequencing run only yielded 2.5X coverage. Therefore, low-coverage imputation was applied to create one SNP profile that could be used for genetic genealogy, kinship inference, ancestry, and phenotype prediction.

What information did the DNA analysis unearth?

The results of the genome sequencing allowed the forensics team to predict that JB55 had been a man with fair skin, brown or hazel eyes, brown or black hair, and a fair amount of freckles across his face.

In order to then confirm the man's identity, the team ran another genome sequencing analysis, this time on an individual buried in the same cemetery, who was believed to have been a relative of JB55.

Once this information was acquired, both files were uploaded to the GEDmatch database, which in turn led to ancestors with the surname Barber who had been living in New England in the 18th and 19th centuries, thereby supporting the hypothesis and confirming that JB55 was, in fact, John Barber.

Not content with stopping there, the forensic team employed the help of Paraborn forensic artist Thom Shaw who used the genome sequencing results to digitially replicate what Barber would have looked like before his life was taken by the disease known at the time as consumption.

"Tales of the undead consuming the blood of living beings have been around for centuries,” Parabon NanoLabs said in a statement regarding their research. “Before scientific and clinical knowledge were used to explain infectious diseases and medical disorders, communities hit with epidemics turned to folklore for explanations.

“They often blamed vampirism for the change in appearance, erratic behavior and deaths of their friends and family who actually suffered from conditions such as porphyria, pellagra, rabies and tuberculosis.

"It is speculated that he [John Barber] was later disinterred and reburied because his limbs had been placed atop his chest in an X in a skull-and-crossbones configuration — a burial practice used to prevent purported vampires from rising from the grave to feed upon the living.”