We all know Terezin was a Czechoslovakian concentration camp.

But it was also where the most highly celebrated Jewish artists composed their last musical concertos, penned one more page in books they would never finish, and took their final bows on stage before being transported to extermination camps.

Notable artists, musicians, doctors, lawyers, and highly decorated war veterans were deported to Terezin by design, so it could be used for propaganda purposes to dispel rumors the world was hearing regarding Jews being killed in concentration camps.

Terezin: A concentration camp for propaganda

Formerly a military fortress town, Terezin was converted into a transit camp in 1941, where 140,000 Jews lived in cramped and squalid conditions. Their beds were straw mattresses, and they fought off fleas, ticks, and mice as they slept. A typical lunch consisted of watered-down soup, a potato, and some turnips.

Approximately 33,000 prisoners died from starvation and diseases such as tuberculosis, typhus, and scarlet fever. Some 88,000 were deported to death camps, the tracks of which were built by Jewish prisoners and ran right outside the camp to Auschwitz.

After long days of work and secretly held classes, 42 boys aged 12-16 were packed into a room called Home One in building L417, which had formerly been a school. The room was so small that two boys had to sleep next to each other in three-tier bunk beds. They closely bonded with each other like brothers. The boys clung on to music and art, and to each other, for hope.

Dr. Valtr Eisinger, a 29-year-old college professor, lived in Home One with the boys and surreptitiously taught them Czech literature and German. He told them about a children’s adventure book called The Republic of ShKID, which describes how homeless Russian boys in the 1920s were sent to a correctional school, where the school’s director encouraged them to establish their own government. They called each other by nicknames and had their own magazine.

The boys of Home One called Dr. Eisinger “Tiny” because of his small stature, but he made an immense impression upon them. They set up their own secret society, also called The Republic of ShKID, replete with a flag, anthem, and a magazine called Vedem, which means “in the lead” in Czech, because the boys always won at sports competitions.

Home One was a converted classroom inside a former school. The boys found a typewriter there, which they used until the ribbon ran out, and then they hand wrote poetry and prose, and documented interviews with people at the camp, such as doctors, nurses, police officers, famous poets, chefs, and professors. They took turns guarding the door, knowing that if they were caught, they would be sent to Auschwitz.

FOURTEEN-YEAR-OLD PETR GINZ was the fearless self-appointed editor-in-chief of the magazine. A talented artist, poet, and writer, he had already authored five novels by the time he was deported to Terezin.

Ginz was the envy of Home One because he was one of the only boys permitted to receive packages of food, since his mother wasn’t Jewish. He used to bribe some of the boys who were not so enthusiastic about contributing to Vedem with lemons, chocolate, and sardines.

Ginz assigned topics for the boys to write about, and if they failed to deliver, he wrote the whole week’s paper himself using different pseudonyms. He slept with the magazine placed protectively on a shelf behind his bed.

While imprisoned, Ginz composed poetry that expressed his longing for home, such as “Memories of Prague” (excerpted from We Are Children Just the Same: Vedem, the Secret Magazine by the Boys of Terezín):

“How long since I saw the sun fade behind the Petrin Hill

With tearful eyes I gazed at you, Prague,

enveloped in your evening shadows

How long since I heard the rush over the weir in the river

I have long since forgotten those hidden corners in the old town, those shady nooks, those sleepy canals.

How are they?

They cannot be grieving for me as I do for them

For almost a year I have huddled in this awful hole,

a few poor streets replace your priceless beauty.

Like a beast, I am imprisoned in a tiny cage

Prague, your fairy tale in stone, how well I remember!”

Lines from his poem “The Madman” express his loss of innocence: “I walk the streets alone and alone, pondering the evil in this world.”

Ginz escaped in his imagination and through his drawings to places as far away as possible. A picture he drew of the world from the vantage point of the moon called Moon Landscape has been to outer space twice. In 2003, Israeli Astronaut Ilan Ramon took it with him on the ill-fated Columbia space shuttle that malfunctioned. And in 2018, NASA astronaut Drew Feustel flew with a copy of it up into space to commemorate Holocaust Remembrance Day.

Every Friday evening after work, the boys recited the Republic of ShKID anthem before reading to each other their weekly contributions to the magazine:

“What joy is ours after the strife,

In Number One we’ve made our bid.

Self-government has come to life,

Long live the Republic of ShKID.

Every person is our brother,

Whether a Christian or a Jew,

Proudly we are marching forward.

The Republic of ShKID is me and you.”

On December 18, 1942, the first issue of Vedem was published, with a celebratory speech made by one of the Home One boys, Walter Roth, which states, “…Torn from our people by this terrible evil, we shall not allow our hearts to be hardened by hatred and anger, but today and forever, our highest aim shall be love for our fellow men, and contempt for racial, religious and nationalist strife.”

The Republic of ShKID was a peaceable uprising; a secret and powerful revolt of the spirit and an affirmation of the unbreakable bonds between the boys.

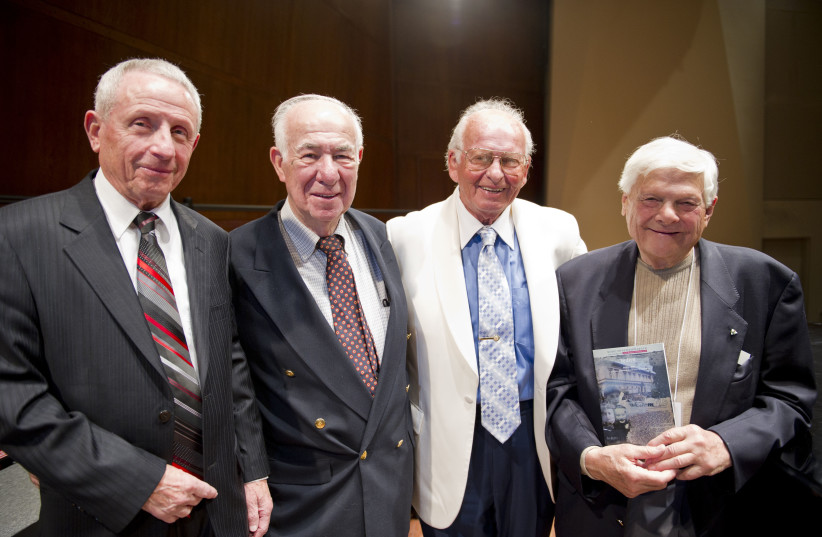

IN 2011, acclaimed American filmmaker and broadcast journalist John Sharify wrote, produced, and narrated The Boys of Terezin, a documentary that shows what he describes to the Magazine as “the reunion of a lifetime.”

Four survivors from Home One – Sidney Taussig, Emil Kopel, George Brady, and Leo Lowy – are overcome with emotion when they reunite after more than six decades. George Brady exclaims, “If in 1944 in Auschwitz, somebody would have told you that we will sit in Seattle 65 years from now, what would you have said? Probably that we died and we are in heaven; and the beautiful thing is, we didn’t have to die to be in heaven.”

Sharify explains, “[In Terezin] they had fun together, which is hard to believe. They would make jokes. They had pillow fights. And then they had this wonderful thing where they were creating this magazine, which kept their minds off of the other things… and they were guided by geniuses.” But, of course, the external circumstances always crept in.

He quotes an excerpt from one of the poems that Hanuš Hachenburg, a young prodigy, contributed to Vedem about a year before he was killed in Auschwitz.

“I was a child, once two short years ago,

My youth was longing for another world.

I’m a child no longer… bloody words and murdered days,

That is no longer just a bugaboo.”

The Boys of Terezin centers around the story behind the world premiere performance of Vedem, a collaboration by Seattle’s Music of Remembrance and the Northwest Boychoir. The choir boys were the same age as the boys of Home One, and they sang the words from poetry in Vedem as the survivors watched their history come alive, with their families in the audience.

Those songs would never have been sung had it not been for one survivor.

THAT SURVIVOR is Sidney Taussig, 93. He courageously saved history when he was 15 years old by saving the magazine.

Taussig was one of 100 boys who passed through Home One. Born in 1929 on the outskirts of Prague, he had an idyllic childhood and was friends with the mostly non-Jewish children in his area. He says, “I used to have only Christian friends. The Czechs weren’t antisemitic… I was able to go to a Catholic preschool because my father knew the priest… I didn’t have to pray with them.”

Taussig explains that the climate of Prague suddenly changed when he was 11 and his teacher said to him, “‘You can’t stay in the class because you are Jewish.’” Taussig adds, “Even though she said she was sorry about it, that was the order.”

In 1942, Taussig was deported to Terezin with his sister, parents, grandparents, aunt, and his close childhood friend, Michael Gruenbaum, with whom he was home-schooled. Gruenbaum’s mother saved his and his sister’s lives at Terezin by sewing teddy bears for an SS officer who liked to give them as gifts. Gruenbaum recently passed away on March 8 at the age of 92.

Taussig’s mother tended to sick people at the infirmary, and his father worked as a blacksmith hoofing shoes for horses that belonged to SS officers.

The Home One boys called Taussig “Trixie” because, he says, “I was infatuated with a girl, and her name was Trixie.” Although too modest to admit it, Taussig was a star soccer player at Terezin. The other boys, like Gruenbaum, very much looked up to him.

Playing soccer helped to distract him from the heart-wrenching job he had been assigned. “I used to take dead bodies to the crematorium. I drew a picture of the crematorium and interviewed the guy who was in charge of it [for Vedem]; we used to play soccer, so I wrote about our games,” he explains.

One Friday night, two German brothers came to Home One to talk with the boys about how in Germany, Nazis were burning books by Jewish authors. “They didn’t want anything Jewish to influence the German youth – only Nazi propaganda,” Taussig says.

The older brother had been in the Hitler Youth training camp – he didn’t know that his father was Jewish because he had been killed by the Gestapo when the son was very young. When the Nazis discovered their lineage, the brothers were sent to Terezin and then deported to Auschwitz.

Taussig secretly had his bar mitzvah at Terezin, officiated by a rabbi his father found in the camp, whom he paid in potatoes. The service was held in a room where Orthodox Jews prayed.

From 1944-1945, all the boys from Home One, except for Taussig, were deported to Auschwitz. Only 15 of those boys survived. When Taussig’s father learned that his son was supposed to be sent to Auschwitz, he lied to the SS leader about how they worked together, and Taussig’s name was taken off the list.

Left alone in Home One with the magazine, which contained about 800 pages of documentation about Terezin, Taussig knew that his life was at risk.

Part of his job at Terezin was to deliver the ashes of dead bodies to the edge of the ghetto for SS men to dump in the river to destroy evidence of the massive number of deaths. When Taussig’s grandmother died of old age, he brought a wooden box to the man in charge of the crematorium, who was Jewish, and asked him if he would put his grandmother’s ashes inside it. Taussig buried the box several feet underground by the side of the blacksmith shop where his father worked, and this became the hiding place for Vedem.

Two months later, in May 1945, Taussig spotted a Russian tank at the gates to the ghetto, and he knew they were about to be liberated. He quickly dug up the box. “I took off with a pair of horses I was driving at Terezin and loaded my parents, my sister, and Michael Gruenbaum onto the horses, and we went back to Prague,” he recalls.

“We traveled to our home, which was occupied by a Czech butcher. The department that directed the return of Czech people from Germany gave us an apartment from a German family who fled before the war. After that, we went to a house which belonged to my uncle. He didn’t return, so we inherited that house on the outskirts of Prague.”

Two years later, Taussig accompanied his sister to New York, and his parents went to Canada. He served in the American Air Force, and after he graduated from Brooklyn Polytech, he became an electrical engineer.

Today, Taussig and his wife, Marion, live in Florida. They have two daughters and a son, as well as nine grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.

“This year, we’ll be married 70 years!” Marion exclaims. She affectionately relays the story of how they met on a soccer field in Queens. “They were playing a game, and I was watching on the sidelines. Somebody slid into Sid, and he went down on the ground and scraped his knee. I happened to be near the first aid kit… I cleaned him up and put a bandage on him, and he went back to play. After the game, he thanked me and said, ‘Can I take you out for a movie or something?’” Nine months later, they were married.

BECAUSE OF Taussig’s bravery in saving Vedem, his story and the stories of the other boys of Home One continue to be told. Excerpts from the magazine were published in 1995 in the book We Are Children Just the Same: Vedem, the Secret Magazine by the Boys of Terezin. Philadelphia-based playwright and choral director Steven Fisher, who is not Jewish, was mesmerized by the book when he found it in a bookstore while visiting Terezin in 2015. “It’s Anne Frank meets Dead Poets Society,” he states.

When Fisher overheard one of his students say that the Holocaust never happened, he took them to Terezin.

When Fisher’s students saw names on the wall of the boys of Home One who had lived there, they wanted to find out if any of them were still alive. They discovered Taussig’s phone number online, and when they called him, he immediately invited them to visit. The next thing they knew, Fisher and two of the boys from his choir were excitedly boarding a plane to Florida. Afterward, they honored Taussig at the Weitzman National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia, where 20 of the choirboys recited poems from Vedem while wearing yellow Stars of David.

Fisher asked Taussig if he could write a play about him. Taussig agreed, as long as he would “make sure there’s laughter and don’t make it just depressing because we were normal boys. If you take away the ordinariness of us, then it somehow takes away the extraordinary thing we survived.” Fisher adds that even though they’re in the Holocaust, “It’s a bunch of boys being boys... They’re fighting with each other… they’re hungry, they have a crush on the girl in dorm number six.”

The Last Boy was the first play to open in New York City in July 2021 as COVID restrictions were lessening. It won four Broadway World awards for Off-Broadway. There was also a Yom Hashoah benefit performance on Broadway last year. Survivors and their families sat in the audience, and Fisher says he “noticed a pattern of survivors asking for aisle seats… they often want to be close to exits.”

The finale of the play takes place at the beginning of Shabbat at sundown when the Russians are liberating Terezin, and Taussig uncovers the magazine he buried in ashes. In describing the Yom Hashoah performance, Fisher says: “As he digs up the magazine, the whole stage streaks in sunset colors, orange and red. At that moment, 100 kids who were survivors’ grandkids all stood up, each with a candle, and the whole room lit up, which showed the 100 boys that were there; and then they all went up on stage.”

Fisher has a film in development that will explore the stories of Taussig and Gruenbaum. It will probably be called Somewhere There Is Still a Sun after Gruenbaum’s book about the Holocaust, seen from his perspective as a child.

Referencing Petr Ginz, who was murdered in Auschwitz when he was 16, Fisher says, “We’re speaking his poetry. He’s alive. In terms of what he might have been, every time the poetry is remembered, every time the play is seen, hopefully when it becomes a film… he lives.”