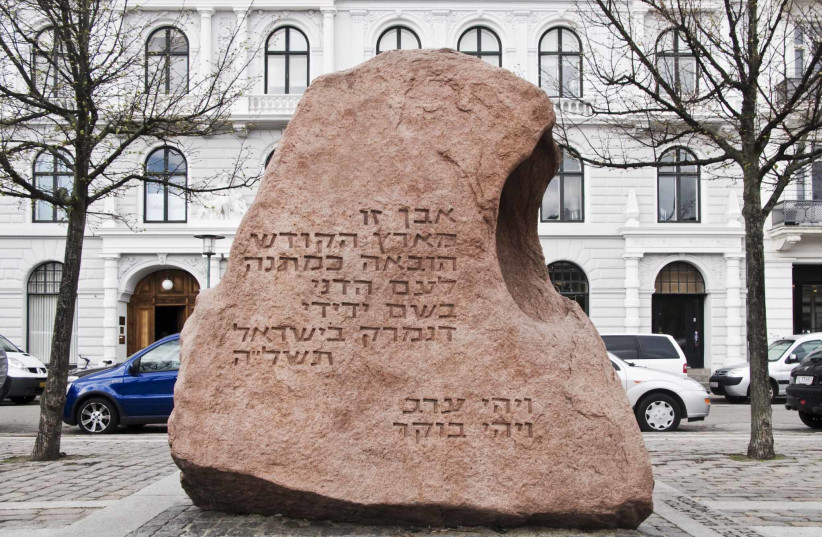

A huge block of red granite stands on a central square in Copenhagen.

On the rock are inscribed the words וַיְהִי עֶרֶב וַיְהִי בֹקֶר– “And it was evening and it was morning.”

The darkness of evening descended upon the Kingdom of Denmark on April 9, 1940.

Hitler’s armies added this small country to Germany’s expanding Reich. It was not considered of much importance by the Fuhrer. It was merely a stepping stone toward the bigger prize of Norway.

Morning would not dawn again until May 4, 1945.

During this long period of darkness, the people of Denmark would become a paragon of virtue for the rest of the world.

Comparisons

By the end of the Second World War, 90% of the Jews of Poland – 3.3 million people – had been annihilated. Of Lithuania’s Jewish population of about 210,000, only 20,000 survived. Other European countries lost over 70% of their Jews. Even Norway, with its tiny Jewish population, lost 42% of its Jews. Denmark saved 7,800 Jews, over 90% of their Jewish population.

How did this miracle come about? There were four main reasons that Denmark would achieve what no other country in Europe did.

‘Benign’ occupation

Firstly, the Nazi occupation of Denmark was eminently benign compared with the unbridled terror that epitomized the rape of other countries. Nazi Germany regarded Denmark as a protectorate rather than an occupied state. Danish King Christian X remained on his throne. The Danish government and its parliament continued to function. The courts continued to administer justice under Danish law and Danish judges. The Danish police force, however, was compelled to work with the German occupiers.

Why did the Nazis allow this to happen? The mighty Reich needed the agricultural produce, the cement, the machinery, and ship production of this Lilliput nation to feed its massive war appetite. So deals were made, compromises sought, and a modus vivendi achieved. One of the assurances was that Jews would not be harmed. There were though minor concessions to the occupiers, such as barring Jews from having prominent public positions.

The Danish government and much of the population took a pragmatic view of the occupation. They believed that it was better to live in reluctant cooperation rather than to perish in hopeless resistance. They accepted the fact that the puny army of their small country with a population of less than four million could not withstand the might of the Third Reich. Some Danes were pro-Nazi. Some of them served with Hitler’s armies as soldiers of Frikorps Danmark, the Danish Free Corps. However, many more Danish men and women joined resistance groups.

This cooperation, or rather collaboration, provokes debate to this day. Denmark’s feeding the ever-hungry armies of the Reich with both food and materials of war was opposed by some. They argued that by saving Danish souls and Danish Jews, Denmark was abetting Hitler in destroying other souls and other Jews.

Demographics

The second factor influencing the miracle was demographic. There were only 7,800 Jews among four million Christian Danes – less than 0.2% of the population. This was strikingly different from the demographics of countries like Poland and Lithuania, where Jews sometimes constituted over 50% of the population of some smaller towns and villages.

Furthermore, most Danish Jews had long since adopted a strategy of invisibility to ward off antisemitism: Yes, we must uphold and nurture our religion, but to succeed here we must become like “them.” We must speak their language, learn their manners, wear their clothes, interact socially with them. We must merge into their midst.

Many of the Jews of other countries, like Poland and Lithuania, were most certainly not invisible. They preferred Yiddish to the vernacular. Many chose dress that distinguished them from their Christian neighbors. They chose not to mingle with their compatriots – or were barred from doing so.

Danish Jews took their chameleon strategy to an extreme. By the time the Second World War broke out, 50% of Danish Jewish men were marrying Christian women, and 25% of Danish Jewish women were marrying ‘’out of the faith.’’ Despite all their efforts to avoid this, “traditional’’ European prejudices against Jews remained widespread. There was, however, very little political, Nazi-type antisemitism in Denmark.

Proximity to Sweden

The welcoming arms of neutral Sweden lay just across a slender finger of water lying between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea. This narrow strait, the Oresund, separates Sweden from Denmark. At its closest point, the Oresund is only four kilometers wide. On wintry days, Sweden is a smudge on the horizon. On clear days, it seems within touching distance. Towers, chimneys, and high-rise buildings are clearly visible.

Freedom for the Danish Jews was but a stone’s throw away; and, moreover, the Swedish government had announced that Sweden would welcome Denmark’s Jews.

For Jews trying to escape most other countries in Europe, there was no such haven close by. Neutral Switzerland accepted 30,000 Jewish refugees, but then sealed its borders to fleeing Jews.

Help from above

The fourth and major factor allowing this miracle to evolve was the help of two men.

SS-Obergruppenführer Karl Rudolf Werner Best was trained as a lawyer. He then became a Gestapo commander. He had helped organize SS-Einsatzgruppen, the paramilitary death squads that were responsible the mass killings of Jews in Nazi-occupied territories. In November 1942, he was appointed as Reichsbevollmächtigter, the civilian administrator of occupied Denmark.

Georg Ferdinand Duckwitz was a German diplomat. He had worked in the Nazi Party’s Office of Foreign Affairs in Berlin. There, he became disillusioned with the credo of Nazism. The Gestapo was aware of Duckwitz’s liberal leanings, as well as the fact that he had once sheltered three Jewish women in his apartment. In 1939, he was assigned to the German embassy in Copenhagen as a maritime attaché.

Duckwitz appeared to be helping the Jews for humanitarian reasons. Best’s motives were less altruistic. He believed that only by maintaining good relations with the Danish government could he ensure the continued supply of Danish agricultural and industrial goods for the Reich. He was aware that any attack on the Jews would disrupt the status quo. There are cynics who maintain that both men had read the writing on the wall. They foresaw that the Nazis would lose the war. They were merely preparing for themselves better defenses in the judicial processes which they knew would follow Germany’s defeat.

The tepid modus vivendi between the Danes and the Nazis functioned relatively well until the summer of 1943. Hitler’s embarrassing defeats at Stalingrad and in North Africa began signaling the beginning of the end. The Reich’s facade of invincibility was beginning to crumble. Den danske modstandsbevægelse (the Danish Resistance Movement) began fighting back in earnest with strikes, sabotage, and guerrilla attacks. Berlin was infuriated and demanded that the Danish government intervene. They refused. A state of emergency was declared on August 29, 1943. Martial law was imposed. The Danish government resigned in protest. The king was placed under house arrest. Officers and soldiers of the Danish army and navy were interned. On September 19, close to 2,000 Danish police were arrested and deported to concentration camps.

Best was summoned by the Fuhrer. Hitler angrily demanded the instant deportation of the Danish Jews. With the opposition of the Danish parliament now out of the way, the road seemed clear at last to make Denmark Judenrein (cleansed of Jews). The mass deportation of Denmark’s Jews was planned for October 1. Best is rumored to have tipped off his Jewish tailor about this plan. It was, however, Duckwitz who, on September 28, passed on the information to Hans Hedtoft, a Danish parliamentarian. Hedtoft informed the Danish resistance and the head of the Jewish community, who in turn warned acting chief rabbi Marcus Melchior. On the day before Rosh Hashanah, at the synagogue Shacharit service, the congregation was briefed about the impending danger. They were told to warn their relatives and their Jewish friends, colleagues, and acquaintances. They were urged to go immediately into hiding. The Danish church disseminated the news to all the parish priests, who were instructed to inform their congregants at church services.

Into hiding

The Jews had three days in which to hide themselves. There followed a whirlwind of activity among all sectors of the population.

Jewish families grabbed whatever items they thought might be useful: money, jewelry, silverware, Kiddush cups, items of clothing, morsels of food, tallit bags, family photos, dolls, toys, first-aid kits.

They left their apartments and their houses. They sought concealment wherever they could find it, wherever it was offered. Jewish individuals and organizations helped find refuge and transport for their co-religionists. Christian Danes working as individuals or in hastily organized networks disseminated warnings, organized hiding places, provided food and transport, scanned telephone books for Jewish names in order to warn them. The Danish Resistance played a major role in the logistics. Nurses, doctors, and administrators hid Jews in hospitals under bogus diagnoses and false names. Copenhagen University closed down for a week, enabling staff and students to participate in rescue efforts. Businesses, political parties, trade unions, sports and social clubs protested and helped in the hiding of Jews. Prisons were emptied of Jewish inmates. Danish police and coastguards, instead of apprehending the fugitives, aided their escape.

Jews were hidden in attics, cellars, spare rooms, and vacant summer houses. They were hidden by neighbors, friends, colleagues, non-Jewish family members – and strangers. They hid for several days or even weeks, uncertain of their fate until transport could be arranged.

So effective was the concealment that the yield of the 1,500 German police in their convoys of lorries that set out from their headquarters at Copenhagen’s City Hall on the night of October 1 to apprehend Jews was only 128.

The king’s Jewish physician, Erik Warburg, the father of Danish cardiology, did not go into hiding. He was arrested. But he was soon released and was never bothered again. Hannah Adler, a school principal, was arrested too but was set free after 400 of her former pupils signed a petition of protest. She also remained in Denmark for the rest of the war.

In the following weeks, the Gestapo managed to arrest more Jews. The number was less than 500.

Flight to freedom

The Jews were smuggled onto coastal freighters, fishing boats, trawlers, row boats, canoes, kayaks, and dinghies – a miniature re-enactment of the evacuation of Dunkirk. Some brave but foolhardy youths attempted to swim to Sweden but perished in the icy autumn waters. A few overloaded, unseaworthy craft floundered and lost their human cargoes.

Old people, the sick and the crippled, nursing mothers, teenagers, and toddlers were loaded on board. They were told to be silent, but who could stop the screaming of infants, the sobbing of mothers, the mumbling of prayers, or the sounds of retching? They were crammed into dark holds which hours before had been filled with fish. The bilge water still held their stench.

The longest crossing of the Oresund was about 150 kilometers. Traveling at nine knots an hour, the journey took about eight hours. Most crossings, though, lasted two hours or less. However, under claustrophobic conditions and in darkness, and suffocated by the stench of fear, vomit, and excrement, these brief journeys seemed to last for eternity.

The refugees waited with racing pulses for the sounds of approaching patrol vessels or the glare of searchlights coursing across the water. Their eyes searched the skies for reconnaissance planes. But none came.

Best had, for some unexplained reason, called in all German patrol boats for painting.

Between six and seven hundred trips were made across the Oresund. Not a single craft was stopped by the Germans.

The picturesque fishing village of Gilleleje was a major staging point for the flight to Sweden. On the evening of October 6, a Gestapo search platoon arrived at the village. An informer led them to the church. They surrounded the church. They set up machine guns and searchlights. A large group of Jews had been given refuge in the parish hall. Others had been hidden in the attic of the church. Eighty Jews were arrested. Most of them were sent to Theresienstadt. This was the only instance of mass arrests during the evacuation.

In all, some 500 Jews were interned in the Theresienstadt concentration camp. About 50 died there. The rest survived the war.

Myths

The most famous myth related to the saving of the Jews of Denmark is that King Christian X wore a yellow Magen David marked “Jude” (Jew) on his chest in solidarity with his Jewish subjects. This is not true. Under the ‘’benign’’ occupation, the Danish Jews were never required to bear the yellow star. However, the king did ride his horse daily through the streets of central Copenhagen to encourage his people in their dark hour. And he contributed both morally and financially to the rescue action.

A second myth is that the Danes saved their Jews because they loved them. While this might have been the case for many, the average Dane who helped in the saving of the Jews did so because of innate Danish values of humanism, egalitarianism, and social justice. They helped the Jews not because they loved them, or because they were Jews. They did so because they were a group of fellow citizens who were being unjustly victimized.

One cloud blocks out some of the sunlight here. Before the start of the war, when the Jews of Germany were already suffering from the Nazis’ racist laws, the Danish government actively opposed the granting of asylum to fleeing Jews.

In my opinion, this should not in any way disparage or diminish the Danes’ monumental achievement of saving their Jews in October 1943, but this corollary needs to be added to the equation.

A further point needs to be addressed. The role of the Danish fishermen. Were they heroes who risked their lives to save Jews? Or had they simply eyed a lucrative source of income? Fees for the Oresund crossing corresponded to five or six months’ wages for a skilled worker. Fees averaged around 1,000 to 2,000 Danish kroner per person (the equivalent of 20,000 to 30,000 Danish kroner, or $ 2,800 to $4,300 per person today).

It is a rare human being who would risk danger, imprisonment, confiscation of one’s source of livelihood or even death to save the life of a stranger. It is neither strange nor reprehensible to seek compensation for such risk. They were heroes.

Some people were transported without payment. Others were charged fees way above the average. Rich Jews were asked to pay more in order to fund the poor. Donations came from Jews and Christians alike.

Conclusion

Hitler had sought to make Denmark Judenrein. In October 1943, after the successful flight of the Danish Jews, Werner Best sent this somewhat ironic message to Berlin: “Denmark has been cleansed of the Jews.”

The Danes’ rescue of their Jews stands unique in the annals of WW II. During that long period of darkness, the people of Denmark enacted Isaiah’s words and became “A light unto the nations.” Eighty years later, their deed is still a beacon for a troubled world.

On that huge block of granite in Copenhagen is another inscription in Hebrew: “This stone from The Holy Land is presented to the Danish nation by friends of Denmark in Israel.”

The name of the square in which it stands is Israel Square. ■

Jack Hoffmann is a retired surgeon who has lived in Denmark with his family for over 40 years. He is the author of the novel He Does Not Die a Death of Shame, set in apartheid-era South Africa.