Certain abnormalities in white and red blood cells, which until now have not been fully understood, were discovered to be caused by a rare defect in the DOCK11 gene.

Germline hemizygous loss-of-function mutations of the DOCK11 gene were, for the first time, shown to cause an inborn error of blood cellular component formation and immunity, which is characterized by severe immune dysregulation and systemic inflammation, recurrent infections, and anemia.

“Such rare and previously unknown diseases provide valuable insights into the fundamental principles of blood formation and the immune system. They allow us to better understand the dysregulated processes underlying these diseases,” explained Kaan Boztug, senior author of the study and Scientific Director of the St. Anna Children’s Cancer Research Institute in Vienna, Austria.

Scientists at St. Anna CCRI published the findings of the study on June 21 in the New England Journal of Medicine. Their research began after a physician in Spain could not make sense of his patient's symptoms.

One puzzling case began the research

The patient in question was a child who suffered from severe inflammation affecting organs such as the kidneys, intestines, and skin, and even after repeated tests, the doctor could not find an explanation.

The puzzled doctor then turned to the St. Anna CCRI for help. He sent the child's blood samples to the center, which is a world leader in the field of rare blood formation diseases and the immune system.

The researchers at St. Anna CCRI sequenced the child's genome and discovered a rare defect in the DOCK11 gene, which contributes to cell communication. The gene wasn't known to be associated with any human disease until then.

“Initially, we had only one patient and therefore did not know which symptoms were related to the gene defect and which were just additional accompanying manifestations. That was quite a challenge.”

Jana Block

“Initially, we had only one patient and therefore did not know which symptoms were related to the gene defect and which were just additional accompanying manifestations. That was quite a challenge,” says Jana Block, a PhD student in Boztug’s research group at St. Anna CCRI.

Therefore the scientists reached out to international connections and found other patients with similar DOCK11 mutations, which helped them gain a better understanding of the disease.

“We work closely with international partner institutions to understand such diseases and help the patients,” said Boztug.

The effects of the rare gene defect

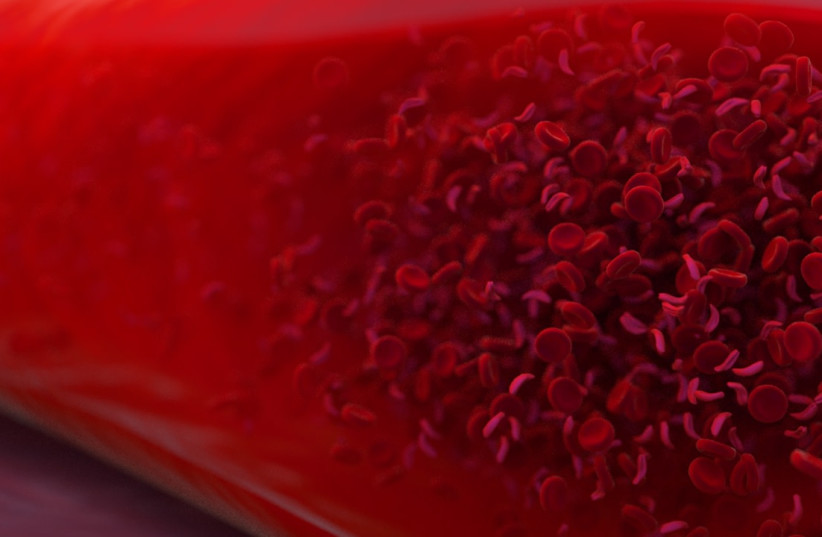

In one of the patients, the DOCK11 defect resulted in impaired blood cell formation, leading to a novel mechanism for anemia, a deficiency of red blood cells. The significantly reduced number of red blood cells requires regular blood transfusions.

The researchers suspect that one way to treat the disease would be to transplant blood-forming stem cells to the patients, but there are still a lot of details of DOCK11’s function which aren't understood.

“Of course, these questions need to be investigated in future studies. It is also conceivable that DOCK11 deficiency could be treated through gene therapy,” said Boztug. “This disease is truly severe, so we see it as our mission not only to understand the biological processes but also to develop effective therapeutic strategies based on that.”

“Our work over the past five years is undoubtedly a significant milestone, but we are also aware that several of the patients have died from the disease,” Block added.