On Shabbat afternoon, shortly before sundown, a neighbor approached me and asked, “Did you hear about the attack in Ariel?”

My immediate reaction was to respond by saying I wasn’t interested, and I could wait until Shabbat was over before being thrust back into what is all-too-often a new cycle of tragedy and pain.

But I admit that I wasn’t able to hold myself back and I asked, “Was anyone killed?”

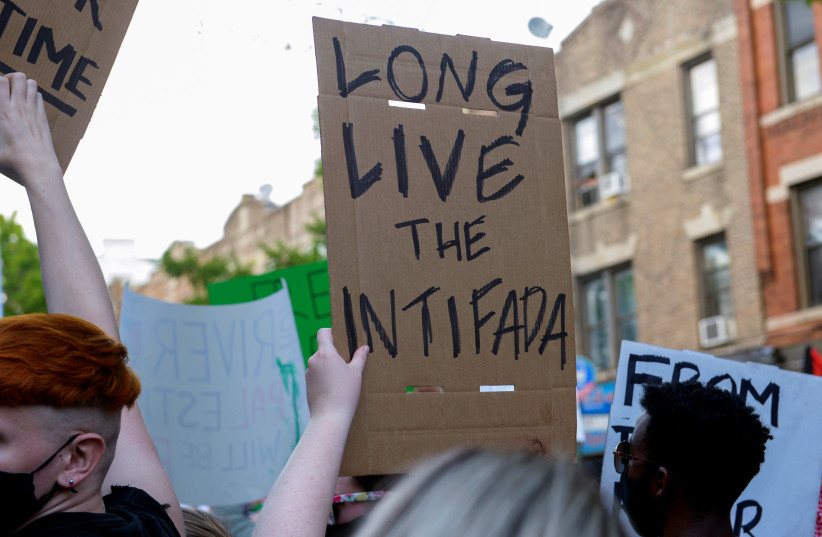

My name is Eliana Mandell Braner, and I am a child of the Second Intifada.

With the murder of my brother Koby in May 2001, much of my life since has been defined by the Intifada. What my neighbor didn’t understand was that even before he shared the details, I immediately knew in my heart that it was terrible news.

For me, and others who share this tragic personal identity, those moments have a definite physical quality. I am momentarily paralyzed and I lose my ability to focus. It takes intense mental effort to get my concentration and breath back and move on to the next task at hand.

The terror attacks in these months of 2022 bring up the same emotions, fears and traumas which overwhelmed me during the Second Intifada. Every news alert about an attack, regardless of the scope or how many victims have been sent to the hospital – or worse – elicits those reactions anew.

My thoughts immediately spiral downward into recognizing the enormous loss that results from these attacks. The families that are left behind, the person whose potential will never be realized.

TWENTY-ONE years ago, just two weeks after my 13-year-old brother’s horrific murder in a cave behind our home, I was sitting with a good friend alone in our home when we heard gunshots. I was only 10, she 14. We heard a loud bang and we soon found out that the rounds had hit the house.

By “luck” we were downstairs at the time while the bullets entered the window of my bedroom on the second floor. For a few moments that felt like eternity, the two of us were there alone before some local teens arrived to save us. They were only 14 but for two petrified girls, their arrival felt like salvation.

We had no idea where to go and felt utterly helpless.

That night, my whole family slept on the lower floor and the next day we left our home in Gush Etzion for a “vacation” in Jerusalem. The local council outfitted us all with flak jackets and helmets, but not enough to protect us all. Indeed on the relatively short drive into Jerusalem we heard bullets fired above our heads.

The next day, an attack occurred in the Russian Compound, just a short distance from our hotel where we had been sent to relax and rehabilitate.

We literally had nowhere to escape the reality.

My high school years were spent in Jerusalem, during the height of the bus bombings. My parents, who had already suffered the trauma of the loss of a child, forbade me and my siblings from taking public transportation or hitchhiking. My school was located at a major intersection that led to the city’s two main hospitals, and the wail of ambulances was an almost constant background noise to my studies.

We learned that if it was just a one ambulance siren then we could believe that it was a laboring mother on the way to deliver a new life – but if the sounds increased to two, three and more, we knew that it was a terror attack. That trauma would intensify minutes later, with the school secretary rushing between the classrooms to check that everyone made it to school safely.

One day, a girl in the grade above me, Hodaya Asraf, was among those murdered on a city bus while she was on her way to school.

When my friends and I were 12, funerals became a routine part of our lives. Even if we didn’t directly know the victims, we would feel drawn to the cemeteries, out of a need to respect those who had paid the sacrifice. When the phone rang early in the morning, we would fear that it was bad news.

SINCE THAT young age, every walk in the street, or ride in a bus or car, has felt like a lesson in survival. I would walk close to the wall or always with a backpack so no one could stab me in the back. Every tractor that passed became a potential threat. Bus rides would be interrupted if I saw someone get on looking even remotely suspicious.

Headphones coming out of a handbag were construed as signs of an explosive device. When I learned how to drive and a car passed me on the side, I would almost instinctively lower myself in my seat, so if it were a drive-by shooter, perhaps that action could save my life.

On and on, the growing list of signs of trauma was everywhere. I remember how every day on my walk home, I was occupied by thoughts of entering the house and finding that my family had been killed.

How would I react? Where would I live? And where would my life take me from here? In my mind, those thoughts weren’t out of the ordinary.

Years later, after I was married, I was speaking with my mother-in-law and told her how I expected the worst. She looked at me and said, “Eliana, that’s not normal!” It was only then that I realized the extent of my personal trauma.

I now know that I live with PTSD. When a door slams or I hear an unexpected bang, my heart jumps and I have to struggle to remain calm.

Today, I am blessed to be a mother. My daily prayer is that this trauma will remain mine alone, and not be passed on to the next generation; that the closest my children will ever come to terror is the knowledge that they had an Uncle Koby, who in 2001 was murdered by terrorists.

The writer is the director of the Koby Mandell Foundation, which runs programs and camps for children and families bereaved from terror and other tragic deaths. The foundation was set up 20 years ago after the tragic murder of 13-year-old Koby Mandell and his friend Yosef Ishran during the Second Intifada.