For 20 years, the EMET Prize, known as the “Israeli Nobel Prize,” has been awarded for excellence in academic and professional achievements that have made a significant contribution to Israeli society. The award ceremony was held last month in the presence of then-prime minister Naftali Bennett, who presented the prize to the 2022 laureates, who received the award in three categories: social sciences, life sciences and the humanities.

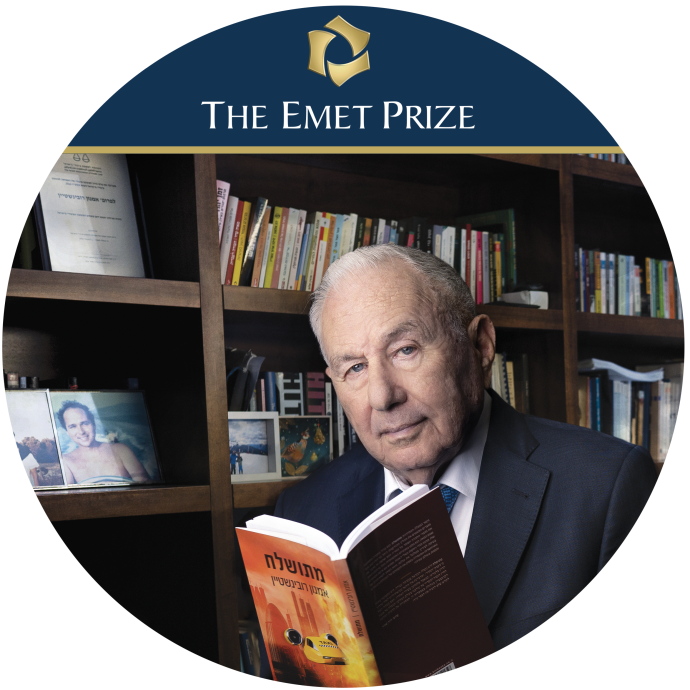

“The prize is a sign of a long career and a journey that I began as a student at the Hebrew University,” says Prof. Rubinstein, professor of law and senior faculty member of the Harry Radzyner School of Law at Reichman University, who was awarded the EMET Prize for his contributions in the field of social sciences.

“After my university studies, I continued to the Knesset, where I was a member for 25 years and served in various positions as a minister in the government for 20 years,” he says.

Prof. Rubinstein was the recipient of the 2006 Israel Prize in Law, and served as education minister in the second Rabin government and the government of Shimon Peres. He has also served as communications minister and was responsible for the reform that introduced landline phones into every home in Israel.

He is considered the father of constitutional law in Israel. His best-known accomplishments in the Knesset were the initiatives to promote the protection of human rights and the enactment of the Basic Law: Human Dignity and Liberty and the Basic Law: Freedom of Occupation.

“I am asked frequently about my achievements, and in my eyes, my greatest accomplishment is the basic laws that protect human rights in Israel. The Supreme Court is entrusted with examining the laws, and the results have been more than satisfactory. This is proven by the fact that the Israeli government presents these laws in international forums. I view this as a personal achievement of which I am proud.”

Are you proud of the country when you look at it now?

“I’m proud of the good things. The State of Israel has many things of which it can be proud. I primarily compare Israel to the US, and when it comes to social rights, Israel wins decisively over the US. I believe in a liberal democracy with complete equality and no discrimination based on race, and I would like Israel to move towards that.”

Prof. Rubinstein grew up in a family in which he was expected to become an economist or businessman, but he wanted to steer his life in a different direction. “Independence was important to me, and the independent path I took for myself in my life is something that has guided me throughout the years. Independent thinking has guided me in my career, in the choices I made and in my writing.”

Not long ago, he celebrated his 90th birthday. When I mention the mistaken announcement of Knesset speaker Avrum Burg in 1999 that announced his death as a guarantee for longevity, he laughs. “I’m recovering from the birthday celebrations. I am delighted, and the book I published a few months ago, Methuselah, deals with life expectancy and extending life,” he says.

“Methuselah” is a futuristic novel that raises deep philosophical questions about lifestyle, eternal life and the importance of death for the future of humanity. Is this something that you think about?

I could have written five books addressing these questions, and questioning whether it is possible to answer them. But the philosophical issue is one that I deal with a great deal in different contexts. I have always dealt with multiculturalism, as well as the question of how to create a society that is both liberal and does not lie to itself.”

Prof. Rubenstein taught at Reichman University until two months ago and has high hopes for the current generation of young people in Israel. “Opening the gates of higher education is a masterful thing, and it is a huge social revolution that narrows the gaps in Israel. I am excited about the students here, and I get a lot of comfort from the younger generation. “I passed through the campus once and saw a group of Ethiopian-Israeli students sitting and singing Haim Gouri’s song about friendship, and my heart swelled. What worries me most is the brain drain.”

Prof. Rubinstein entered the political arena in 1974 when, as part of the protest movements after the Yom Kippur War, he founded the Shinui party. Two years later, he joined forces with Yigael Yadin to establish the Dash party – The Democratic Movement for Change. He remained with Shinui as it divided and joined other parties. In 1992, Shinui joined with Ratz and Mapam to form Meretz. Rubenstein remained in politics until his retirement in 2002 after 25 years.

Do you have any regrets?

“I have always chosen the more difficult path in my career. I could have joined a large party list whose members were appointed by a committee, and perhaps looking back at the atmosphere in Israel, I was not necessarily right. I had to follow a difficult path with Shinui. I could have taken this challenge and reached a position of power to influence things that I wanted to happen in the country, but it’s crying over spilled milk. I’m sorry, but I’m not really sorry, because I’ve always believed that hard work produces good results.”

How optimistic are you?

“Sometimes I’m optimistic, and sometimes I’m pessimistic. The fact that the basic laws on human rights were passed by a large and absolute majority and have not faded since then is spectacular and encourages anyone who believes in Israel’s future. As far as the part that is less good? The Jewish people have survived dreadful things – even Pharaoh.”

“We cannot avoid partial solutions”

Prof. Lapidoth of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, founder of international public law in the State of Israel, was awarded the EMET Prize for her contributions to the social sciences, in teaching, research and practice, spanning more than 60 years.

“I was a soldier in the War of Independence – a 17-year-old girl in the medical corps even before there was a medical corps. We were in an operation in the South, and I was holding the plasma of the wounded soldiers, which made a strong impression on me. I already thought then that something had to be done to prevent future wars,” Prof. Lapidoth says when I ask why she chose international law.

“That’s how it started. I didn’t think about peace then, but about the wounded.”

She is a graduate of the first class of the Faculty of Law at the Hebrew University and was the first woman in the Faculty of Law in Jerusalem, but she does not make much of it. “I was also the only female legal adviser to the Foreign Ministry, but I never thought I was breaking glass ceilings. I didn’t do anything special that others couldn’t have done.”

Prof. Lapidoth, who was chosen to light a torch in honor of Israel’s 47th Independence Day, is considered a world-renowned researcher in various fields of international law, with a particular emphasis on maritime law, the study of autonomy and the status of Jerusalem. She served as the Foreign Ministry’s legal adviser during the critical years when the peace agreement with Egypt was completed, and follow-up talks on autonomy in the territories began.

“When we started working in the field, there were not many experts on the subject in Israel,” says Prof. Lapidoth, “but today, in government ministries, such as the Transportation Ministry and the Finance Ministry, there are experts in international law. There are many more treaties in existence today, thanks to the improvement of relations between Israel and the countries of the world. Every lawyer today should study international law.”

It seems that the issue of sovereignty of Jerusalem has been going on forever and is unsolvable.

“Jerusalem is part of the Palestinian problem. At the very minimum, they want east Jerusalem as the capital of the Palestinian state, and there is a peace proposal that was put forth by the Arab states in 2002, which stated that Israel must withdraw from all the territories it occupied, including east Jerusalem. But Israel did not agree to this.

“Over the years, we have looked for all kinds of interim solutions that might allow us to reach some kind of compromise. What I have proposed in the past is to leave the issue of sovereignty alone. The Knesset will never ratify a treaty that renounces sovereignty, and the Palestinians will not approve the opposite, so we must find interim solutions.

“Either they will be silent about sovereignty and talk about the division of powers, or in some areas, they will agree on common sovereignty, or they will say that sovereignty belongs to God. There are all kinds of options that soften the possibilities.”

How did you resolve the Palestinian issue then?

“In the peace treaty with Egypt, they did not want to make a separate peace, and they did not want to be different from the other Arab countries. That is why the Camp David Accords were signed together with the peace treaty, where they agreed on the foundations of the peace treaty with Egypt but also signed an agreement regarding the future of the Palestinians. They did not ignore the problem but wanted to solve it so that they could advance the peace treaty with Israel.

“Today, the situation is not much different, but many Arab countries have agreed to improve relations with Israel, and the Abraham Accords are a significant milestone. But this is certainly an existing problem that needs to be solved.”

Is it possible in international law to maintain objectivity, especially in the sensitive situation in the Middle East?

“International law is part of international relations and I have no illusions that everything depends on the law. Nonetheless, when it comes to the countries’ essential interests, they do not always uphold international law, such as Vladimir Putin, who is acting against international law.

“There is a wonderful book by American jurist Louis Henkin that examines important international conflicts and shows the influence of international law on them. The effect is ultimately for the better.”

With more than 60 years of research behind you, what has changed in international law?

“I’m afraid that not much has changed. What has improved, perhaps, is a bit of the recognition that humanitarian behavior is also needed in Ukraine – the recognition that something must be done to make things easier for the people suffering from war.

“There is already talk that after the war, war criminals will be put on trial. But it is not so simple. In order for the ICC to have jurisdiction, it must be shown that the country in question is subject to the Rome Statute and the Statute of the International Criminal Court.”

You once wrote a comprehensive article on the Arab proposal on refugees.

“It was an interesting proposal from 2002, but there are two fundamental problems for the refugees. One is the definition of who is a refugee. In 1948, there were 700,000 refugees at most, and today they claim 6.5 million, which is completely illogical.

“The second issue concerns the country that will agree to absorb them, and of course, we must support the resettlement of the refugees. I believe that if there is goodwill, it is a problem that can also be solved in the future.”

What does receiving the prize mean to you?

“I was delighted when I learned about the award. I didn’t know that the prize was also awarded in the field of law, and my selection made me very happy. I thank Prof. Daphna Levinson Zamir (dean of the Faculty of Law at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem), who submitted my candidacy, and my teachers who accompanied me over the years.

“I am currently updating the book about the Basic Law of Jerusalem, the capital of Israel, and I intend to issue it in a second edition, and I am updating a chapter on Jerusalem in a book on international law.

“Still, I’m allowing myself a bit of retirement.”

This article was written in cooperation with the EMET Prize.

Translated by Alan Rosenbaum.