The elegantly dressed man of 43 adjusted his tie. In the mirror, he saw his younger self as he had stood there, in Basel, just six years earlier, in 1897, preparing to address 200 delegates about the Jewish state that would one day arise.

That day, thunderous applause had shaken the hall. Now, it resounded in his mind.

“If not in five years, then in 50, yet it shall be!” he had said.

Theodor sighed as he looked into his reflected eyes. They were the same eyes, but the dream, had it changed?

He pulled out his watch from his coat pocket. In eight minutes the congress would begin. His younger version vanished from the mirror.

Theodor approached the hall with measured steps and opened its doors. Six hundred pairs of hands applauded politely, marking the opening of the Sixth Zionist Congress. He looked around the assembly of delegates, immediately recognizing, by their furrowed brows and worried expressions, those who had already heard the proposal.

“They don’t understand the dangers if we do not act immediately,” he thought. “Don’t show any signs of weakness, just keep moving,” his reflected twin urged in his imagination. He straightened his posture.

The silence in the hall was frozen. No one dared utter a word; coughs were stifled.

“My fellow delegates, this congress is unlike any that has come before it. Words are not enough. There is no point in sitting idly by and praying for salvation when we have a choice. And we do have a choice. His Majesty has offered us a beautiful land, a fruitful land, a land where we can live in peace...”

“A foreign land!” The burning accusation came from a bespectacled delegate.

“To live in a foreign land in peace, Ze’ev,” Theodor replied to young Jabotinsky.

The mirror began to crack, but he did not back down.

Not backing down

Since that meeting with the Right Honorable Joseph Chamberlain two months earlier, Theodor had, in his mind, already rehearsed the harshest possible objections and opposition to the plan.

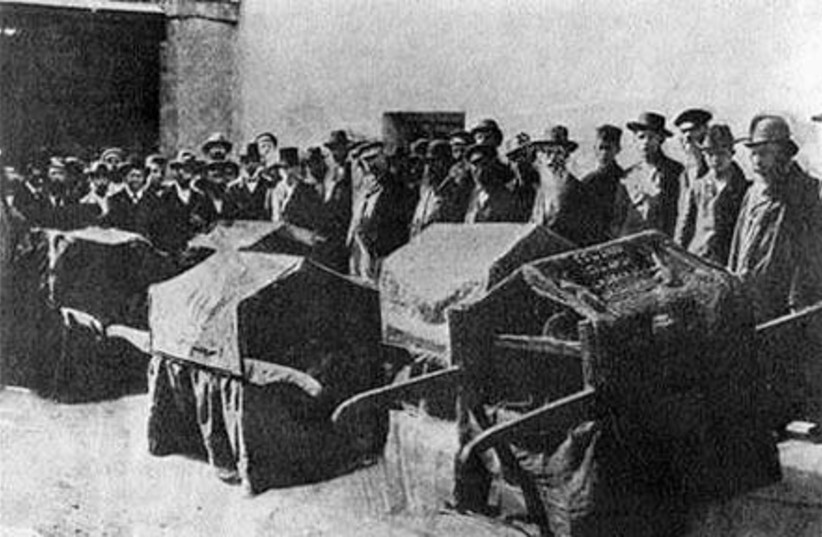

But he would not surrender. Not since the rumors, the stories, and the pictures of the scenes of the horrors had emerged from Kishinev.

Theodor continued: “His Majesty King Edward VII’s generous proposal is to establish a Jewish state in a land that rents water and natural treasures, a land where we can gather as a people urgently...”

He paused, took a deep breath, scanned the faces of the delegates, and finished: “In Uganda.”

The renewed silence rippled across the hall. Part of the delegates remained silent in agreement; others maintained a furious silence. The first to break it was another young student.

“What kind of Zionism would this be, exactly, without Zion, Mr. Herzl?” It was Chaim Weizmann. It had been clear from the outset that Jabotinsky and Weizmann would oppose the plan.

A third voice opined without hesitation, it was Yisrael Zangwill, the leader of the Territorialists: “At least Zionism without Zion is better than Zion without Zionism!”

Opponents’ voices sounded throughout the hall.

“Where is the Alt, the old country you promised? This is only a Neuland, a new land.”

“Liar, liar! Your whole book is just a tale, an agada!”

“If we will it? The question is if you will it?”

Finally, Theodor spoke up: “This is just a stop on the long road to Zion. Ladies and gentlemen,” but his voice was drowned out in the sea of shouting.

He raised his large arm and pointed his finger as if it were a spear: “Who among you will oppose this plan?” he thundered and threatened with his finger.

“Will he or she be able to say in the next pogrom, in the next Chisinau, that ‘Our hand did not spill this blood?’ Let us save those who can still be saved.”

For a moment, out of respect, the delegates listened to Theodor. Then their suppressed anger burst forth and the debates became noisy and terrifying.

Theodor descended from the stage and set out on an urgent search for the plan’s opponents, who did not understand that their foolish resistance would engulf them all in a raging stream. He reached a group that he thought formed part of the rebellious camp. To his surprise, this group seemed completely calm. It seemed as though they had come to terms with such a radical idea from the start.

“Rabbi Reines,” he whispered to his friend from Eastern Europe, “do you not object to my proposal? What about: ‘Im eshkacheh Yerushalayim tishkah yemini?’” he quoted the few Hebrew words he knew, remembering the tears glistening in his grandfather’s eyes as when Theodor recited them under the chuppa on his wedding day.

“If you are looking for the voice of the opponents, don’t look for it on our side, Binyamin Ze’ev,” he said addressing Theodor by his Hebrew name. “Pikuach nefesh, a matter of saving lives overrides everything else, even Shabbes. The land has been waiting for us for many years, it isn’t going anywhere.”

Theodor moved on through the confusing bustle, looking around at the scattered eyes.

As he rushed over to his brothers from the West – those dressed in tuxedo suits and Pandora hats – he felt someone give him a hearty pat on the back.

“Excellent idea. Mr. Herzl. There really is no time to wait, not after riots like these., Our brothers in East Europe are poor, they are trampled under the wheels of antisemitism. The fact that we are lucky and live in Germany or France does not mean that we have the right to stop such a fateful decision.”

It was Max Nordau. It was good to know that the people closest to him supported him, thought Theodor.

Suddenly a representative from the East spoke out in a loud, angry, voice with a Russian accent.

“What is Zionism without Zion? Who is for Zion to us, who is for Jerusalem to us? Zionists of Zion, gather!”

Theodor hadn’t expected this. The opposition had snuck up from behind. Lying in wait were the socialists and the liberals, the “camp of the apikorsim” as they were known by the Orthodox.

Theodor rushed towards them, trying to salvage what he could. “My friends,” he said as he intercepted them on the way out, at the large hall’s doors, “we don’t need to swear loyalty to a foreign land; all I ask is that we show appreciation for His Majesty’s gesture and show that the Jewish people are ready to cooperate. If we reject his generous proposals, the British will continue to regard us as stubborn Jews with no true interest in serious negotiations. We must unite.”

“Exactly, Mr. Herzl!” Jabotinsky replied. “It’s time to unite around Zion. Zionists of Zion,” he called out loudly, naming a group that had just been born, “please gather for a true Zionist Congress in the parallel hall.”

The mirror shattered completely, and Theodor could no longer recognize himself in it, only fragments of dreams remained. He blocked their way as they exited the hall and implored them with outstretched arms:

“My friends, my friends, please! Let’s not repeat our mistake. Zion is just as precious to me as it is to you. If we don’t unite now, we will continue to be wandering Jews for many years to come. Please hear the gesture of His Majesty’s appreciation to the end.”

As Theodor tried to gather the broken pieces, a young man’s mocking voice sounded from the back.

“It is important to you! Probably as important to you as your Judaism, Theodor. You’re a politician, Mr. Herzl, and if to achieve your goals you needed to convert us all to Christianity, you wouldn’t hesitate. And here you are again kneeling before the so-called noble Englishman. You’re a traitor, a traitor!”

In the shards of cracked mirror that remained in his mind, Theodor caught the reflection of Gen. Alfred Dreyfus, as he had stood at the Place de l’Ecole Militaire in Paris, with his hands tied and his head bowed, as curses and accusations were levied at him: “Death to the Jews! Death to Judas Iscariot!”

Theodor’s hands dropped to his sides, and his tears began to flow. Tears for the suspicion, tears for the accusations, and tears for the terrible rupture he sensed was about to occur. “These youngsters don’t understand that their hot blood can bring disaster upon us all,” he thought.

“Let’s take a vote, like any democratic organization,” Theodor attempted with his last reserves of energy.

The Zionists of Zion were convinced. They knew that no true Zionist would choose this foolish and humiliating proposal.

The fateful hour was set, and the minutes of waiting stretched like wandering years.

It was time. Theodor took the stage once again.

“Gentlemen, Uganda is not Zion, and it never will be, but please know that the only way to make a dream come true is by being willing to be flexible with it.

“Please let only two representatives come up and give the final speeches.”

Two delegates went up and began the last battle to capture the hearts of the voters.

“This is a temporary shelter only,” explained one.

“But who guarantees that we will not settle there as a permanent solution?” countered the other.

“Finally, a real land of our own — and not just a dream or a prayer.”

“But Jews will never be willing to leave their homes unless it is for the Promised Land.”

Suddenly, eloquent Hebrew was heard from a back bench in the audience.

“And why is it so important that we return to the land of the Bible? After all, we have all turned our backs on the past, this is our glory!” It was Eliezer Ben-Yehuda.

Israel Zangwill added: “If we return to Eretz Yisrael, it will also return to us! The oppressive tradition in the Diaspora will oppress us 1,000 times more since it will be at home. The rabbinical government will only grow stronger and stronger.”

There were boos from some delegates, and although Rabbi Yitzchak Yaacov Reines remained silent, he frowned and shook his head.

Theodor felt the need to intervene. He turned to the group of the Zionists of Zion.

“This is for you, our brothers from the East. Don’t you understand? We, in the West, do not face the same dangers as you do, and our neighbors are not as barbaric as yours. We, for ourselves, have no reason to hurry. If we wait one more day, it is only a day, but who knows what a day can bring for you? This is the time to act!”

Theodor’s remarks took center stage. Perhaps it was his pure heart, perhaps his genius rhetoric, but something in him struck the audience.

“They’re just stubborn,” Zangwill shouted at him; “they’re like angry children who just want to cry and don’t really want to solve the problem.”

“You think you’re so wise, so calculated, so noble in your proposal,” sneered Yacov Bernstein-Cohen, a Russian Zionist born in Kishinev. “We’ll be uprooted to Uganda, what then? You think the problem will go away? Don’t let your pity rule you! If we defer to His Majesty’s proposal, indeed your pricking conscience will be assuaged, but if you really want to help us — to help yourselves for God’s sake!

“Don’t be tempted to treat the sick tree from its branches, but from deep in its roots.”

The long hour of persuasion and insults came to an end, and the delegates convened for the fateful vote.

The voting slips were wet with tears, and each person felt the earlier generations watching as they cast the votes to decide the future of the Jewish people forever. Each camp was sure that the opposing camp represented the greatest danger to the Jews since the days of Haman.

At the end of the count, Theodor took to the stage with a face that gave nothing away.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” he said, as a slight smile lifted the corners of his lips. “There is a time when a people determines its destiny. Enough with distant dreams, enough with pogroms, enough with shedding the blood of our sons and daughters. Today we begin to move. Apart from the many abstainers, the conclusion of the vote is clear and unequivocal. Honorable delegates, spearheads for the salvation of our people, get ready. We have chosen Uganda.”

Applause was heard from half the room, but about 100 participants booed and headed to the parallel hall.

The first day of the congress was over. The hot day had come to an end. On his way back to the hotel, Theodor enjoyed the summer evening breeze that caressed his beard and blew through his hair.

The man in the mirror in his room was wearing pajamas, he smiled a thin smile of relief, and then sighed. Before he could get into his bed and close his eyes, there was a knock on the door. It was Max Nordau.

“They’re still there, Theodor. They’re in the parallel hall, lying on the floor as if it’s Tisha B’Av. They’re crying and crying, and grieving.”

The man in the mirror put his suit back on at 2 a.m. and went out on a rescue mission. In his heart, he knew that this actuation was even more important than the previous one.

“Let me in, please,” he knocked on the hall door only to hear cries of “Traitor! Traitor!” He was about to give up when a muffled argument arose on the other side, and finally the door opened. It was Bernstein-Cohen.

“I’m sorry, Mr. Herzl, these young people sometimes lose their manners.”

Theodor sat down on the floor and would not leave the hall until he managed to convince them to go to hear him the following morning in the main hall.

The next day, the man in the mirror wore the same suit, but he noticed a new silver hair sprouting in his beard.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” he opened the second day of the Sixth Zionist Congress with piercing eyes and an open heart.

“We will certainly send our people to Uganda and examine the proposal, but remember that a picture of a landscape, however beautiful it may be, will never replace the real thing, no matter how shiny it may be,” he told the delegates.

“Uganda will only ever be a stop on the way to Zion.”

Theodor took a deep breath, looked at Rabbi Raines, and quoted, in the few words of Hebrew that he knew: “Im eshkacheh Yerushalayim tishkah yemini.”❖

The writer is an educator, tour guide, and author of the Zionist children’s book Storkey’s Journey Home