“I love to work on parchment,” says Neriah Israel, with a joyful reverence in his voice while explaining his craft. “It is such a Jewish thing. Think about it... from the beginning it was part of us. Part of Jewish tradition. Moshe Rabbeinu wrote the Torah 3,000 years ago on parchment and we as Jews have been continuing to do so ever since. If a Sefer Torah is not written on parchment, then it is prohibited. So I love working on parchment,” Israel says with a smile. “And my art is always inspired by it.”

Born to an Afrikaner Christian family in Marquard, a small farming town in South Africa’s Free State province, Israel’s Jewish journey to his adopted homeland began at a young age, and would prove to be both unique and fascinating.

“I come from a rural part in South Africa and grew up in a small town,” says the 48-year-old Israel. “Later I went to high school in a bigger town, where I learned how to draw and took art as a subject.”

His road to pursue art as his passion did not come without a few bumps along the way. “I failed art for three years,” Israel reminisces with a chuckle. “My art teacher told me: ‘look, you are not good enough.’”

Yet despite these harsh and discouraging words, Israel eventually passed art with distinction in matriculation, and then went to study art for a year at the Free State Technikon in Bloemfontein. He later dropped out because he did not see much of a future in it at the time. Instead, Israel went on to complete a business-related diploma and begin his career as a quality engineer. His work would bring him to London, where he discovered a small synagogue in the city.

“I started to learn about Judaism before I came to this particular synagogue,” says Israel in describing the beginning of his journey toward Judaism. “I was a Christian. I came from a Christian family. Personally, I was very religious and came from a religious family. But then I started to question a few inconsistencies [about Christianity], which I could not reconcile.”

“I was a Christian. I came from a Christian family. Personally, I was very religious and came from a religious family. But then I started to question a few inconsistencies [about Christianity], which I could not reconcile.”

Neriah Israel

Israel describes this period as a challenging time in his life, filled with much spiritual questioning and reflection.

“It was a very difficult time,” he says. “Of praying, studying, asking... day after day. Questioning something means you have to be prepared for answers you won’t necessarily like.”

While in London, Israel was welcomed by the rabbi of a local synagogue, and found joy in becoming part of its community.

During this time, Israel kept coming back to a verse from the Book of Malachi:

“Behold I send my angel, and he will clear a way before me. And suddenly, the Lord whom you seek will come to his temple. And behold! The angel of the covenant whom you desire, is coming, says the Lord of Hosts.” (Malachi 3:1)

“Behold I send my angel, and he will clear a way before me. And suddenly, the Lord whom you seek will come to his temple. And behold! The angel of the covenant whom you desire, is coming, says the Lord of Hosts.”

Malachi 3:1

“I came to the rabbi as a Christian and asked him about this verse,” says Israel. “The rabbi explained the Jewish interpretation, and afterward invited me to come over for Shabbat. I never stopped going to synagogue since then, even though I was still a Christian at the time.”

“By Purim that year, I knew I wanted to be a Jew. But by that point I needed to make a decision to either begin my process for conversion or become a Noahide.”

According to Orthodox Jewish law, non-Jews are under no obligation to convert to Judaism. But they are required to observe what is known as the Seven Laws of Noah to be assured a place in the World to Come.

These seven commandments are enumerated in the Babylonian Talmud as follows: 1. Do not worship idols 2. Do not curse God. 3. Do not murder 4. Do not commit adultery or other forms of sexual immorality 5. Do not steal 6. Do not eat flesh torn from a living animal 7. Establish courts of justice.

“I made the decision to become a Jew because I felt a very strong connection with the people in that community. It was a small synagogue and a very close-knit family.”

During his time attending this synagogue, Israel would familiarize himself with Machon Meir in Jerusalem through the online courses broadcast by the yeshiva.

“I came to learn at Machon Meir with the specific aim to convert to Judaism,” explains Israel. One of the State of Israel’s most unique and engaging Torah-outreach organizations, nestled in the Jerusalem neighborhood of Kiryat Moshe, Machon Meir is widely known as a destination for non-Jews from all over the world seeking an Orthodox conversion to Judaism that is recognized by the state. Israel was impressed by the yeshiva’s unique program that emphasized a deep love and appreciation for the land of Israel.

“The program didn’t have one overarching view that all the rabbis had to conform. For example, one shiur [lesson] would come from a haredi rabbi, while another would be taught by someone who is more National-Religious. Each rabbi had his own way of teaching, and that made it very enjoyable, because you’re not just being taught one particular view of Judaism, you are exposed to many different styles. So I think that when a student walks out of Machon Meir and later decides to create a life in this country, they can adapt flexibly to other environments whether it be more haredi or National-Religious.”

In 2015, Israel left England and began his program of study at Machon Meir. He has many fond memories of his time at the yeshiva, though in the beginning when he arrived in Israel for the first time there were significant cultural shifts due to the language barrier.

“For me, the culture shock was not knowing the language,” Israel says, recounting his arrival at Ben-Gurion Airport while not knowing a word of Hebrew. “I took a sherut and told the driver that I wanted to go to Machon Meir... but I ended up being taken to Machon Lev [Jerusalem College of Technology] instead! I had no idea where I was, but thankfully the guard at the college understood what happened and got me a taxi to go to Machon Meir. By then, the sherut came back and explained to the other taxi he made a mistake, so he didn’t charge me.”

Despite that rocky start, Israel maintains it was all worth it to finally come home to his adopted namesake.

“It was early in the morning,” he fondly describes the moment he finally reached Machon Meir. “I wanted to go to the Kotel very badly, and my roommate agreed to come along with me. Neither of us had any money and he literally walked with me in the summer heat. It was true hesed. The sun was rising. To see Jerusalem for the first time in my life... with its trees and hills... it was beautiful. I couldn’t believe it.”

Israel would undergo a process of study for his conversion that would last almost two years at Machon Meir, under the tutelage of Rabbi Yosef Dinkevich. A typical day would begin with morning prayers, then breakfast. The morning would be filled with lessons on Jewish law. After lunch, some of the students would go off to ulpan. It was not uncommon for evening lessons to go on until one o’clock in the morning.

“I had the privilege of studying weekly with Neriah Israel,” says Rabbi Aharon Halevy, who has been teaching in the Machon Meir English Department since 2005. “I was extremely impressed by his dedication and desire to soak up as much Torah knowledge as possible in each of our study sessions. Additionally, Neriah was always eager to discover new ways to implement whatever he learned from the rabbis.”

“I was extremely impressed by his dedication and desire to soak up as much Torah knowledge as possible in each of our study sessions. Additionally, Neriah was always eager to discover new ways to implement whatever he learned from the rabbis.”

Rabbi Aharon Halevy

“One thing that was very important,” says Israel, “was that the yeshiva also connected students with host families for Shabbat. It hearkens back to the hospitality that was characteristic of Avraham Avinu. I think that particular aspect of Machon Meir is unique because students can see how Jewish family life functions. It is a different experience, since you develop a bond with a family.” Following his conversion, Israel found that he needed to quickly fulfill a practical need.

“After Machon Meir, I needed to immediately find work,” says Israel, relaying the sense of urgency he felt at the time. “Most people who study at the yeshiva would like to spend more time there. But I needed to earn a living.”

One Saturday evening, Israel found a new opportunity open up for him while waiting for a bus from Kiryat Moshe to Baka. A man who took the same bus also happened to have a friend from South Africa who worked as a quality engineer. Prior to going their separate ways, the man gave his friend’s contact information to Israel. Two weeks later, Israel would receive a call with news of a new job opening.

“It could not have come at a better time,” Israel sighs with relief, “because until that point it was so difficult for me to find a job.”

He worked in Haifa at Philips, a Dutch multinational conglomeration specializing in the manufacture of medical equipment. A year and a half later, Israel moved to the southern city of Dimona and worked at Vishay Intertechnology, a global manufacturer of semiconductors and passive electronic components.

While happy in his new home, circumstances involving his personal health and employment status sadly took an unfortunate turn in recent months.

“I worked at Vishay for about a year and a half,” says Israel, “until I started to develop extreme eye pain whenever I worked with an electronic display like a computer or a cellphone. In the end, I could no longer work behind a computer screen long enough to complete my responsibilities as a quality engineer.” Though this turn of events would be burdensome, it did allow Israel to go back and revisit his original passion of becoming an artist.

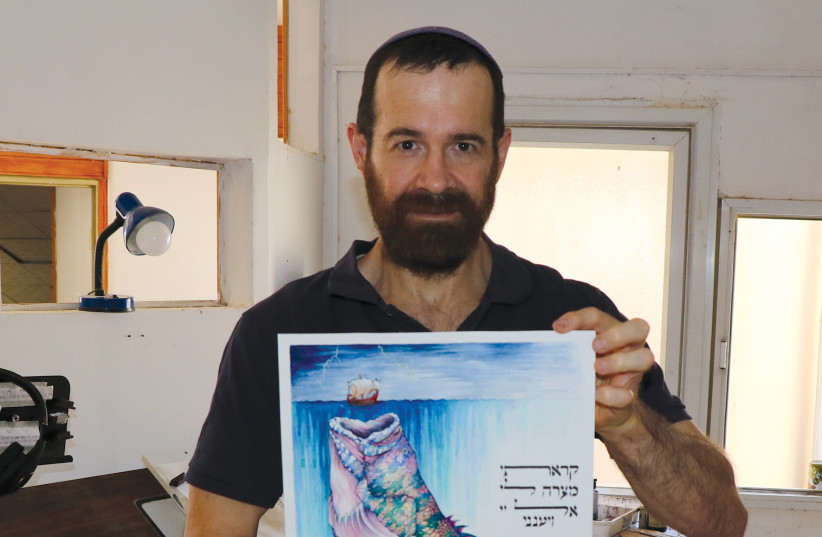

“I love the Tanach!” exclaims Israel describing the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible. “My inspiration would come from there. I am specifically interested in the Book of Jonah and [the theme] of the prophet who, at first, did not want to carry out his mission. The big fish, the mysterious plant... these are themes that appear frequently in my work.”

Israel explained the creative process that he goes through in composing his artwork, while also employing his newfound skills in the ancient art of Hebrew calligraphy.

“While I was in Haifa, I decided one evening to attend this class because a friend I knew was interested in becoming a sofer [i.e. a Jewish religious scribe]. I wanted to become a sofer, but shortly after attending the class, I was offered a good job in Dimona. I took the job, but after a year and a half, the circle took me back to the beginning and I contacted the rabbi whom I met in Haifa.”

It would take about a year for Israel to become a sofer stam, a certified religiously observant Jewish scribe who can transcribe Torah scrolls, tefillin, mezuzot and other religious writings. Though primarily making a living as an artist, his work often combines calligraphy with other forms of artistry, in a unique combination of beautiful colors and patterns that serve as the background for verses in the Hebrew Bible.

“I love those aspects of my art,” he says with palpable admiration for his craft. “I also love taking photographs of the Old City of Jerusalem, and then painting these settings on parchment. I mix the pigments with chicken eggs, it is an ancient technique. The end result really is something.”

Regardless of what the future holds, Israel has come a long way from being a South African newcomer who knew barely enough Hebrew to properly order a taxi cab.

“When I first came here, all I knew was the word shalom. At this stage of my life at least, I am acutely aware that it is just temporary. Life is temporary. We pass through life... everything is just a passage of time. Nothing is a permanent condition. Not our families, not our friends, not what we own, not our health... neither is my art. The ability to draw or to paint is something that I am just borrowing and Hashem is just lending it to me. In the end, everything that I do, whether a painting of Jerusalem or transcribing some part of the Tanach, whatever I produce, it’s just a journey.

“Everything that I do, every piece of art or work that I write, in the end... it is an expression of thanks to the Eternal. And I hope that I use it well, until the time comes that I have to give it back.”

Israel’s artwork and Jewish ritual writings can be seen and purchased on his website at neriahisraelart.com. ■

Bradley Martin is Executive Director for the Near East Center for Strategic Studies. Follow him on Facebook and Twitter @ByBradleyMartin