While European Jews became outlaws and persecuted, Cecilia Pels and a group of activist Jews in Copenhagen sent food and comforting words to the oppressed Jewish families of Nazi Germany and the occupied countries. Their effort was discovered only recently when Yad Vashem in Jerusalem opened a black box which contained letters and postcards from families on the receiving end of these parcels from Copenhagen. The aid operation is one of the most remarkable Danish endeavors from the time of the war and a story of true valor in the face of Nazi oppression.

Persecuted Jews of Europe

It would be a simplification of the events of the Holocaust and other tragedies of the 20th century to state that the National Socialists were solely responsible. The vast scope of Holocaust with its six million Jewish victims only came about through the help of other groups and governments of Europe, which directly or indirectly helped the Nazis. As deportations to concentration camps in Eastern Europe began, national authorities often assisted in arresting and deporting Jews, e.g. in France and Norway. Until October 1943, Denmark returned Jews, many of them stateless, to Germany and occupied countries where they would end up in concentration camps. As the killings accelerated in Europe, the governments of Romania, Poland and Hungary all lent a helping hand to the Nazis. It must also be added how Communists gladly took part in this murder spree, e.g. at the Katyn Massacre where scores of Poles fell victim to Stalin’s regime.

Many others than just Jews were on the receiving end of these 20th century atrocities. Romas and Sintis were persecuted with about half a million deaths, the mentally ill were euthanized and about 3.5 million Russian prisoners of war died from starvation and maltreatment. Yet, no group was persecuted as systematically and given as little protection as the Jews. Even the Red Cross did not wish to intervene on their behalf as Nazism had filtered through its ranks in both Denmark, Germany and other countries.

Help did come from one unexpected source though as shown by the box in the possession of Yad Vashem. The box contained postcards, letters and photographs telling the unique story of aid brought from Denmark to the destitute Jews of Europe. The postcards and letters found in the box were addressed to Cecilia Pels, living at Dyrkøb 3, Copenhagen, Denmark. Who was Cecilia Pels and the people around her whom distressed Jews warmly thanked for parcels containing food?

The Pels family – From Germany to Copenhagen

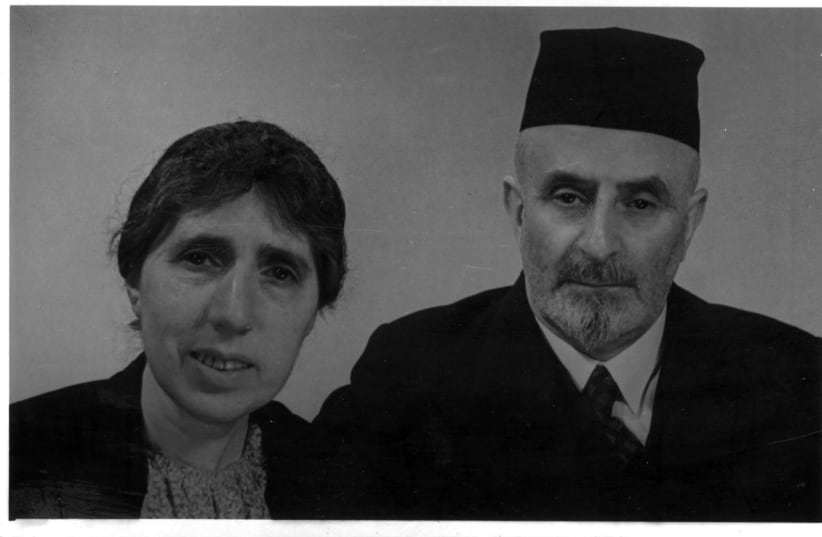

Figuring out the inhabitants of Dyrkøb 3 is not a problem: The address is located in the old town of Copenhagen, the house itself being a Jewish retirement home by the name of Joseph Frænkel’s Home for the Elderly. A married Jewish couple by the name of Cecilia and Ludwig Liepmann Pels lived in the house. Cecilia, née Cohn, was born and raised in Hamburg and had married Ludwig Liepmann Pels whose family came from the northern town of Emden, he himself trading in wines. They had three daughters: Martha, Lisbeth and Irma. Martha went to Copenhagen where she married Liepmann Kurzweil, a teacher at the Jewish school. As Jews were assaulted and synagogues burned down on the Night of the Broken Glass in November 1938, the Pels family lost a large part of its possessions. Cecilia and Ludwig Liepmann Pels had long been applying for a residence permit in Denmark, and in 1940, they left for Copenhagen and their daughter Martha in order to escape the Nazis, while Irma traveled to modern-day Israel and Lisbeth to London.

Most of the family was murdered by the Nazis.

The aid work begins

By then, the Pels couple were already above the age of 60 and refugees in a new city with only a temporary residence permit. They were of Orthodox affiliation, and both became active members of the Jewish community of Copenhagen. Cecilia joined the Jewish women’s sewing club, which each year organized a charity event with the profits going to needy Jews and students in Palestine. As such, charity work was already part of the activities in the Jewish community, and Cecilia and Ludwig Pels had themselves received parcels from their daughter Martha, while they were living in Hamburg. German Jews were subjected to harassment and humiliation by the Nazis, losing their work due to boycotts with starvation as a result. Now, Cecilia Pels began sending food parcels to her relatives in Hamburg. She received letters of thanks, urging her to send parcels to other Jewish families in need. It quickly became apparent that the need for parcels was immense. The letters also contained information about deportations of German J

ews eastward as well as news of recent deaths. The letters were subject to strict censure resulting in extremely careful wording. From an orphanage for girls in Hamburg, Cecilia Pels received moving messages from the girls and their wardens about daily life. The letter had been kept in the black box and reads as follows:

“It is with gratitude that we have received the latest parcel. On Friday night, we used it to serve a nice soup and also sausage with mashed potatoes. Soon we will also have green cabbage with meat, which we are all looking forward to in excitement. Every time we eat these nice things we think of you as it is you who has given us these delicacies. For Hanukkah, we received the chocolate sweets that we asked for, the better part of which came. A magician also came[…] Did you enjoy this Hanukkah too, Mrs. Pels and Mrs. Kunstadt? The wardens had added: “If you knew how little delight we have in our lives, you would understand the joy brought to us by your parcels. The children are not even able to express their joy and gratitude in a letter, and you should have seen their beaming eyes as we gave them the presents.” The letter was dated to 21st December 1943. Of the girls in the orphanage, only one, Ruth Geistlich, survived.

The aid work is expanded

Cecilia Pels understood that more had to be done, so she established an organization under the Hebrew name of “Kesher shel Chesed” (“Link of Charity”). The organization provided the opportunity for benefactors to join and send parcels by posing as relatives, which allowed the parcels to move through German customs unhindered. Sending parcels was expensive and, being refugees, Cecilia and the other participants did not have the means to do so. It was therefore decided that the money collected at the annual charity event would be redirected from Palestine to Jewish families of Europe. As the senders were not relatives, the parcels were in fact illegal. The board of the Jewish community under the leadership of supreme court barrister C.B. Henriques sought to avoid provoking the German occupation force and adhered strictly to the Danish authorities’ request to keep a low profile and stay out of sight. That is the reason why the board of the community, according to Yad Vashem, expressed opposition to the activities of Link to Charity, but the Pels-run organization ignored the warning and continued its activities. Doubts must be sown over the information of Yad Vashem though as a lot of the mail coming back to Denmark was addressed to the retirement home, which Axel Margolinsky, an influential figure in the community, was in charge of. He can hardly have been unaware of what was going on, and there was likely a tacit agreement between the Pels organization and the community leadership as even Chief Rabbi Max Friediger’s name was written on some of the parcels.

One of the women in the project was Cecilia’s daughter Martha, who had married a Dane and therefore was a legal resident of Denmark. As Martha spoke Danish as opposed to the other active women, she took on the job of recruiting people to the operation as well as sending parcels through postal offices. As keeping a low profile was of greatest importance, the parcels were distributed from a number of far-away postal offices. Swift transportation was necessary as a result, and we know from Yad Vashem that a young Jewish man by the name of David Sompolinsky – later also an active participant in bringing refugees to Sweden – took part in these operations. Cecilia Pels and others in her group did not have Danish citizenship and ran the risk of being deported to the Theresienstadt concentration camp and from there to Auschwitz.

Parcels across Europe

As time went on, the parcels also started to move east to the ghettos and forced labor camps of Poland. In the black box, one finds a postcard from such a labor camp near the Polish town of Lodz, written by a L. Szlamowicz. Parcels also went out to Amsterdam and France. In his testimony to Yad Vashem, David Sompolinsky writes:

“We did actually have mail correspondence with the ghetto in Lodz for almost two years. Parents, children and siblings to Jews in the ghetto were permitted to send a parcel every month containing five kilos of food. A small group of activists gathered around Mrs. Pels. They came up with relatives to Jews on the ghetto list. I do not remember where these lists came from. The work in ensuring funds for the deliveries and finding people who under oath and under threat of imprisonment would sign off as relatives was a liberation of the soul at a time when waiting to see what would happen was the only thing we could do. There was no guarantee that the Jews would receive the parcels, but we received postcards as receipts. The message on the postcards was always the same: “We are still alive, thanks to the parcels, we are managing, please send more.”

The Pelses escape to Sweden

In October 1943, Cecilia and Luwig Pels and their family had to flee to Sweden in order to avoid capture by the Germans. Their aid work has hitherto been known only to Yad Vashem, and recently the Danish historian Dr. Phil. Silvia Goldbaum Tarabini Fracapane has mentioned their effort in the newly released The Jews of Denmark in the Holocaust: Life and Death in the Theresienstadt Ghetto. According to Fracapane, the Pels group was behind sending parcels to more than 200 individuals as well as a number of institutions. Commenting to Berlingske, she says: “The parcels of the Pels group were vital for the Jews receiving them, even if most of them were eventually murdered. It is an effort only made known to us now, but it is an important one and tells us about both what the refugees actually knew and also what was possible for them do.” She believes that the aid work had positive reverberations: The majority of Danish Jews, including Mrs. Pels and the other senders of parcels, managed to escape to Sweden in October 1943, but 470 Jews were deported to Theresienstadt. In February 1944, a group of Danes organized by the doctors Richard Ege and Poul Brandt Rehberg began organizing parcels for Theresienstadt. As there was little certainty over who had been deported and who had managed to reach Sweden, the letters from Theresienstadt were used as indicators. Among the letters were letters of thanks from people in Pels’ network of parcels. At least 25 people, who had been receiving these packages, continued to do so when Danish prisoners came to Theresienstadt. Among them were for example the married couple Ketty and David Goldschmidt of Hamburg.

Following the liberation of Denmark, the whole Pels family returned to Copenhagen. Cecilia Pels died in 1965, aged 83. No mention was made of this brave woman and the effort of her group following the war. Martha Pels-Kurzweil’s grandchild Margalith tells that this operation was never spoken about within the family either. Only in 2005, she was made aware of the case by Yad Vashem, which had received the black box, but the story has not been told in Denmark until now.

This article was first published in the Danish newspaper ‘Berlingske’