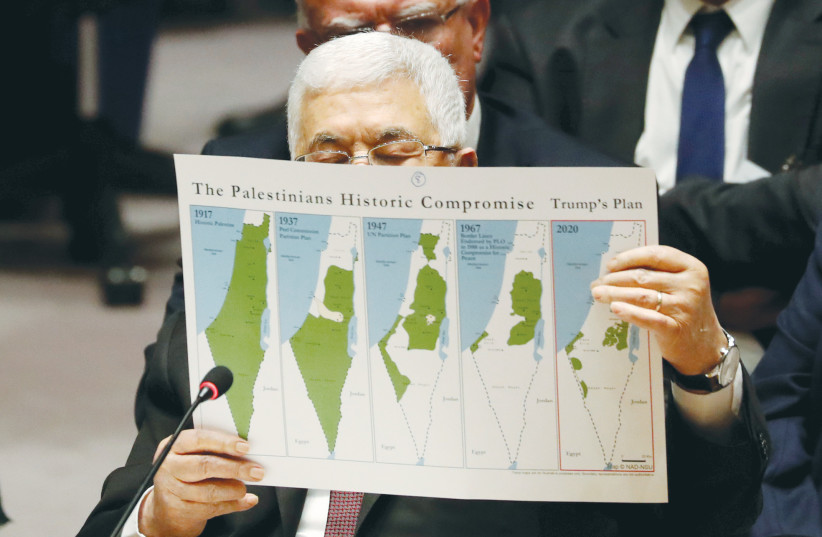

In recent years, the Palestinian narrative usually includes a series of maps purportedly showing the disappearance of Arab Palestine.

It starts by showing a map of Palestine in 1922. This is followed by a map of the UN partition plan of 1947, followed by the post-1948 borders of Israel, Gaza and the West Bank, and finally the breakup of the West Bank into smaller zones as a result of Israeli settlement activity.

However, a series of maps showing the gradual disappearance of the Mandate of Palestine from a Jewish perspective would be an appropriate counterstatement. A key component would be the map that resulted from the Peel Commission Report of 1937.

On July 7, 1937, 84 years ago, the report of the Palestine Royal Commission, also referred to as the Peel Commission after the six-member commission’s chair, William Robert Wellesley, Earl Peel, was submitted to Parliament. The commission was established by the British government in August 1936 in response to violent clashes between Palestinian Jews and Arabs, instigated by the Arab leadership to force the British government to curtail Jewish immigration to Palestine.

The complete report, a 400-page document available on the Internet, is a remarkably detailed analysis of the situation at that time. It was completed and submitted a mere seven months after the commission first arrived in Palestine to begin its deliberations.

The first 15 to 20 pages of the report constitute a concise review of Jewish history including the biblical period, the dispersion resulting from the revolts against the Romans, the history of Jewish life in the Diaspora (both good and bad), the scourge of antisemitism, and the development of modern Zionism. It notes the continued Jewish presence in Palestine: “…since the fall of the Jewish State some Jews have been living in Palestine… Fresh immigrants arrived from time to time.”

For historical context, it is important to recall that for 600 years, the Ottoman Turks (a non-Arab Muslim people) dominated much of the Middle East, southeastern Europe and North Africa. By the 20th century, however, the Ottoman Empire shrunk in extent and influence, consisting mainly of what is today modern Turkey, including a much reduced European component, as well as the parts of the Middle East that were referred to as Greater Syria (including what later became known as Palestine), Mesopotamia, and most of the Arabian peninsula.

Turkey sided with the Central Powers (Germany and Austria-Hungary) in World War I, but by 1918 Turkish losses at the hands of the British in Palestine and Mesopotamia meant the end of the Ottoman Empire. The modern state of Turkey rose from its ashes. However, the fate of the remaining Ottoman territory, a vast expanse of close to 3,000,000 square kilometers in area (a million square miles) has proven to be more resistant to political solutions, and conflict and uncertainty persist to this day.

In Seven Pillars of Wisdom, Thomas Edward Lawrence (“Lawrence of Arabia”), the charismatic British Army officer who led the Arab Revolt against the Turks, identifies the Arabic-speaking areas of Asia as a parallelogram occupying an area about the size of India, but with a much sparser population. Lawrence refers to 20,000,000 Arabs in the early 1900s, consisting both of nomadic Bedouin tribes and townspeople. While governed by the Sultan from Istanbul, with the help of the Turkish army, areas of local autonomy existed, the most important of which was the Hejaz, an area of western Arabia containing the two Islamic holy cities of Medina and Mecca. The ruling family was the Hashemites, direct descendants of the Prophet Mohammed, and Hussein bin Ali, Sharif of Mecca, was the Emir at the onset of World War I.

In 1908, the Turkish government completed a railroad extending from Damascus to the city of Medina in the Hejaz. Its primary purpose was transporting Muslim pilgrims making the Haj, but was also useful to the Turkish army in maintaining its grip on the Arabian Peninsula.

Lawrence, along with forces under the emir’s son, Faisal, attacked the Turkish army in several raids, the most successful of which was the capture of the port of Aqaba located at the northern end of the Red Sea. However, it was the Hejaz railroad that was the main target, and they did succeed in disrupting Turkish supplies and troop movements.

In 1917 and 1918, a series of decisive British victories under General Allenby at Beersheba, Jerusalem, and Megiddo led to the collapse of the Turkish forces in Palestine and helped end the Turkish war effort.

After the war, the four principal allied powers (Britain, France Italy and Japan), with the US observing, settled the disposition of the Arab portions of the Ottoman Empire at a conference in 1920 in San Remo, where Britain was granted a Mandate to govern Palestine. San Remo also promoted the 1917 Balfour Declaration, in which Britain committed itself to establish a National Home for the Jewish people. These decisions were endorsed by the League of Nations in 1922.

There were two snags: first, the British had also agreed to share the spoils with France, resulting in the assignment of the area of today’s Syria and Lebanon to French oversight. This meant that Faisal, who aspired to rule Syria as a reward for his contribution to the war, could not claim Syria as his kingdom, nor Damascus as his capital. He had to make do with Iraq and Baghdad. The second snag was that the Hashemites lost their base in the Hejaz to a rival tribal group centered in the eastern zone of the Arabian Peninsula, the Saudis. By the 1920s, the Sauds were in complete control of the Hejaz, including Mecca and Medina.

Out of a sense of obligation to the Hashemites, the British government in 1921, under the stewardship of Colonial Secretary Winston Churchill, cut off the eastern three-quarters of the British Mandate of Palestine, that is the portion east of the Jordan River, to create the Emirate of Transjordan, with Abdullah, the second son of Hussein bin Ali, at its head. Thus, at a stroke, Palestine was reduced in size from about 45,000 square miles to about 10,000 square miles, or about 1% of the landmass liberated from Ottoman control.

Much has been made of British perfidy in promising the same land to two peoples, but that was hardly the British perception. Until the British Mandate, there was no territory labeled Palestine. The territory that is now considered to be Palestine was known as a part of greater Syria, and the Hashemites, as represented by Faisal, were primarily interested in Syria.

The Peel Commission Report makes repeated reference to the vastness of the Arab territory liberated from Ottoman rule and the small size of the area allocated to the Jews, noting that ”Palestine… was a relatively small, slice of territory, and, as matters stood at the end of 1918, the Sherif and his family had gone far to realize their ambitions. The whole of the Arab world had been freed from Turkish despotism.”

The report includes a detailed analysis of the Mandate’s operations, including topics such as Public Health, Public Security and Education and Immigration. It notes that the bulk of new immigrants during the 17 years of the Mandate were Jews, but it doesn’t rule out the possibility that some of the increase in the Arab population was due to migration from surrounding areas as a result of economic opportunities created by the Jews in Palestine. It notes for example that …”The general beneficent effect of Jewish immigration on Arab welfare is illustrated by the fact that the increase in the Arab population is most marked in urban areas affected by Jewish development.”

At the time the report was written, the population of Palestine was about 1.3 million (400,000 Jews and 900,000 Arabs.) The report noted that what the Arabs wanted most was national independence and what they feared most was Jewish domination; and what the Jews wanted most was the freedom to absorb as many immigrants as possible, and what they feared most was being a permanent minority in Palestine.

The commission considered that the gulf between the two populations was too wide to bridge, and recommended that Palestine be partitioned into a Jewish State and an Arab State. The Jewish State, constituting only 17% of the Mandate, would include a coastal strip from Rehovot and Tel Aviv northwards, as well as all of the Galilee. The Arab state would make up 75% of the total, while the remaining 8%, mainly Jerusalem and its surroundings, would continue to be governed by Britain.

To reduce the potential for future conflict, the commission also recommended a population exchange between the Jewish and Arab states, along the lines of that what took place between Greece and Turkey after the Greco-Turkish War of 1922. The larger Arab population would bear the brunt of the exchange.

The report concludes by summarizing the gains and losses for Jews and Arabs offered by the partition plan. However, it is the Arabs that are the primary focus of the concluding remarks, and the tone used is a supplicating one: “There was a time when Arab statesmen were willing to concede little Palestine to the Jews, provided that the rest of Arab Asia were free…(if) partition is adopted, the greater part of Palestine will be independent too.” And: “Considering what the possibility of finding a refuge in Palestine means to many thousands of suffering Jews, we cannot believe that the ‘distress’ occasioned by Partition, great as it would be, is more than Arab generosity can bear… If the Arabs at some sacrifice could help to solve that problem, they would earn the gratitude not of the Jews alone but of all the Western World.”

These words are a far cry from those used by Churchill when speaking to a delegation of Palestinian Arabs who were complaining about the Balfour Declaration during his one and only visit to Palestine just 16 years earlier (1921), when he stressed that it was the armies of Britain, not the Arabs of Palestine, that had overthrown the Turks, and that the Jews were in Palestine by right, not on sufferance.

The Arabs rejected the proposed partition outright. In fact, the Arab leadership boycotted the commission’s deliberations, although they did participate in the final sessions.

The partition plan was discussed and debated in August at a meeting of the 20th World Zionist Congress in Zurich, just a few weeks after the Peel Commission Report was released. There was disappointment in the small size (less than 2,000 square miles) of the proposed Jewish state, as well as Jerusalem, with its significant Jewish population, not being included. However, the precarious circumstances of European Jewry were an overriding concern. According to Walter Laqueur (A History of Zionism, 1972), Weizmann and Ben-Gurion argued in favor of accepting the plan, with reservations, and the vote in favor was 300-158.

In the end, it did not matter. The British were not willing to force the Palestinian Arabs to acquiesce, the Peel Commission Partition Plan was quietly shelved, and Britain imposed a severe limit on Jewish immigration at a time of greatest Jewish desperation.

In 1938, a new commission led by Sir John Woodhead made one more effort to come up with an acceptable partition proposal. That commission, again boycotted by the Palestinian Arabs, resulted in a complex and unworkable scheme that tried to alleviate Arab worries by increasing the size of the Mandatory portion of Palestine to include the Galilee. The Jewish State would consist of a small coastal area approximately 500 square miles in area. This proposal was rejected by both sides, and while its rejection by the Zionists was understandable, one can only wonder at its rejection by the Arabs. It was certainly a much better deal, from the Arab perspective, than the 1947 UN Partition Plan, which was also rejected by the Arabs.

I believe that most Jews in the Diaspora and in Israel empathize with the Palestinian predicament, and support the search for an acceptable two-state solution. However, my feelings are tempered by the knowledge that Palestinian intransigence in 1937 over a proposal for a tiny Jewish land helped make it impossible for Jews to escape the Holocaust.■