One of the Torah readings for Shmini Atzeret/Simchat Torah is the weekly portion Vezot habracha. It contains the fewest letters and the fewest words of any parsha and is the only parsha read in the evening. In the morning it is read along with the beginning of the Creation story of Genesis. The parsha includes the last words of Moses to the Jewish people and closes with the description of his death, burial, the 30 days of mourning, and Joshua taking on the leadership.

The parsha opens with: “This is the blessing with which Moses, the man of God, blessed the Israelites farewell before he died” (Deut. 33:1).

Moses, who had spent so much of his time admonishing the people, decided as his final missive to bless them. It raises the question of whether Moses, at that moment, as he reflected on his life and his work, ever doubted his leadership style over those 40 years. Or whether, while still in agreement with his approach, he felt, as he took his leave of the people, that a blessing was called for.

In either case, this question gives us pause to contemplate the effectiveness of both approaches – the carrot or the stick – when it comes to how to influence people. That Moses chose to bless as he took his final leave of the people is an important lesson for us.

The last word of the Torah is 'Israel'

The last word in the Torah is “Israel” (Deut .34:10). Why? One explanation is that the rest of Tanach (which includes the Writings and the Prophets along with the Torah) will comprise some 700 years of the history of ancient Israel – from the time of Joshua through Ezra and Nehemiah. If we combine the first two words (which are also the name) of this week’s Torah portion with the last word in the Torah, we get “vezot habeacha Israel” (this is the blessing of Israel). In other words, the entire Torah is a blessing for the Jewish people. But it can only become the blessing it was intended to be if we engage with it continuously.

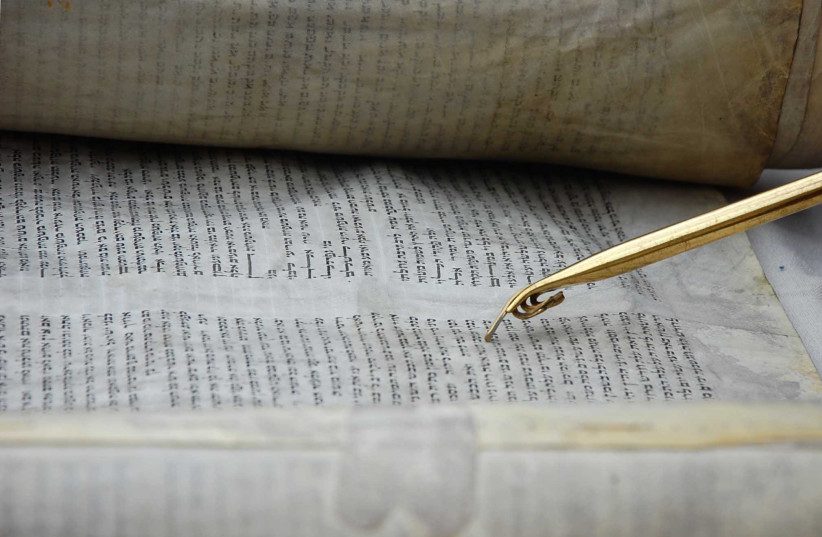

This is why during the morning services of Shmini Atzeret/Simchat Torah, as soon as we finish reading our parsha, as soon as we complete the annual cycle of reading the Torah, we immediately start all over again and read the opening of Genesis. Another way to understand the centrality of the Torah to the Jewish people is that the last letter of the Torah, lamed, and the first letter of the Torah, bet – spell out the word lev, or “heart.”

How many books have we read that we start all over again upon their conclusion? And even more so, annually? (For some, the closest example might be the Harry Potter series.) Generally, once we read a book, we close it and move on to another one. We might pick it up again, but often years later. So why this uninterrupted reading of the Torah year after year? One reason is that it contains unlimited knowledge. We are told in the Mishna:

“[Tannaitic sage] Ben Bag-Bag said: Turn it over, and [again] turn it over, for all is therein. And look into it; and become gray and old therein; and do not move away from it, for you have no better portion than it” (Avot 5:22).

There is the excitement of seeing something new that we may not have noticed before, even having read it over, year after year. There are so many details and connections within the Torah, and we bring fresh eyes each time we read its holy words, causing us to notice and interpret the words differently.

In this way, we can liken the yearly reading of the Torah to a Rorschach test of who we are. When we notice something different in the text, what is it that allows us to see it, even though it has been right in front of our eyes for years, perhaps even decades?

With this approach, we learn not only something new about the Torah but also about ourselves. We need to ask: Why is the Hebrew letter lamed the last letter in the Torah? Lamed is the first letter of three key words: lilmod, lama, and lechem. Lilmod means “to study”: The study of Torah (and study in general) is paramount. Lama means “why?”: Asking questions is fundamental to understanding. Lechem is “bread”: The Torah is food for the soul.

In closing, the letter lamed is also the first letter of the infinitive form in Hebrew, thus it is the letter leading to action – and the Torah is our guide to those actions. As J.K. Rowling has Dumbledore say in Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, “It is our choices, Harry, that show what we truly are, far more than our abilities.”

We are told in our parsha that Moses’ last words to us are about the Torah as a heritage (Deut. 33:4). While his death is described soon after those words, his teaching remains from generation to generation. Spanish Nobel laureate Vincente Aleixandre captured that sentiment so well in his poem “Como Moises Es El Viejo” (The Old Man Is Like Moses):

“A sunset will do for death/A serving of shadow on the edge of the horizon./A swarming of youth and hope and voices./And in that place the generations to come, the earth, the border/The thing the others will see.” ■

The writer is a Reconstructionist rabbi emeritus of the Israel Congregation in Manchester Center, Vermont. He teaches at the Arava Institute for Environmental Studies at Kibbutz Ketura and at Bennington College.