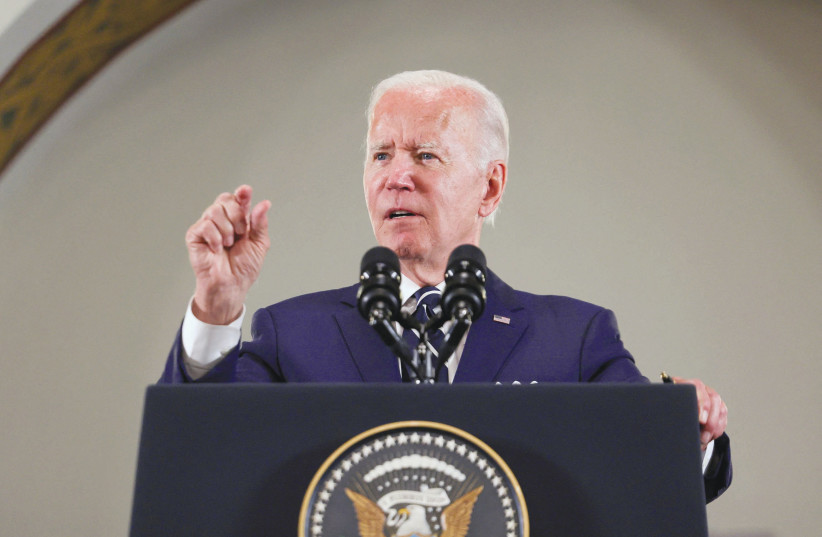

US President Joe Biden’s visit to Saudi Arabia was very important. On the one hand, Saudi Arabia has been a key US partner for many decades. In fact, US policy in the region could be said to rest on the pillar of Saudi Arabia.

At the same time, however, the US has other friends and allies in the region. Historically, the US is also a key ally of Israel, and the US has now cultivated partnerships with the UAE, Qatar and Bahrain, as well as Egypt and Turkey.

Other countries, such as Iran, were once friends of the US. Now they are enemies. The US has also left Afghanistan and lost influence in Iraq. But the US has forces in Iraq and Syria.

The shifting policies of the US in the region are of interest. Turkey is ostensibly a NATO ally of the United States. Throughout the past decade, however, Turkey’s far-right regime has turned against America. The AKP party, which rules Ankara and which has imprisoned most opposition journalists and many opposition politicians, has turned Ankara into an ally of Iran and Russia. Ankara’s regime works closely with both countries, either on issues regarding Syria or even on defense and trade deals.

The evolution of US-Saudi relations

Meanwhile, US-Saudi relations have also been difficult in recent years. The Obama administration appeared to turn against Saudi Arabia. Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia also shifted towards a new era of reform. This reform was not to the liking of some countries in the West, though.

Some groups that had once relied on Riyadh for funding, including think tanks and human rights groups, were angered to see Saudi Arabia and the UAE turn against the Muslim Brotherhood (MB). That is because there is a quiet inroad that the MB, despite being a religious extremist group, has cultivated in the West. When Riyadh turned on these Islamists, some of the westerners who had been close to a different generation of Saudi insiders moved to Qatar and back to the West to re-orient themselves into an anti-Saudi lobby.

How does this relate to the Biden visit?

On Friday, Biden met Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman Al Saud. The National reported that they had “talks on wide-ranging issues including aviation, energy, Iran, Yemen, human rights, and sovereignty over islands in the Red Sea.”

This is important – but it is also a test.

There were voices in the West trying to sabotage the Biden trip to Israel and Saudi Arabia. For these voices, the trip represents the worst of both worlds. For many years, a lobby in the US that has worked against Israel has also begun to turn on Saudi Arabia. For them, the Biden trip was a nightmare. No “two-state solution” and no “Iran deal” was going to come of it. They didn’t get the human rights talking points either, whether it was a statement about Shireen Abu Akleh or Jamal Khashoggi.

The anti-Saudi lobby: History, flipped

The small but loud anti-Saudi lobby in the US is a true reversal of how things were in the 1990s. In those days, Saudi Arabia was the most favored ally and former US diplomats, members of Congress and security officials all adored Riyadh.

Oddly, it was in the 1990s when Saudi Arabia’s policies were fostering anti-American views and Riyadh had a checkered record on confronting extremists. In those days, Saudi Arabia was also more anti-Israel. When Riyadh became more amicable to Israel, suddenly the anti-Saudi lobby appeared.

Those human rights experts who had bashed Israel and been happy to endorse Riyadh, suddenly moved to found “human rights” groups that would focus on the actions of Egypt, Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Bahrain. Why? Because those were the countries at peace with Israel.

The message was clear: There is a dedicated group of people in the West, some of them former officials, who back Iran and are against any country that makes peace with Israel. Some of these lobbyists clothed themselves in the guise of “realism” but quietly they believed Iran having a nuclear weapon would bring stability to the Middle East. They wanted to “balance” Israel and also undermine any country that was a friend of the West.

As such, the new anti-Saudi talking point is that the US shouldn’t “go to war” for Saudi Arabia or be tied to Saudi Arabia, Israel, the UAE or Bahrain. For them, the only countries they usually want to “engage” with is Qatar and Iran. They also want a soft stance on Russia when it comes to Ukraine, and they tend to back China.

The anti-Saudi effect

The overall effect of the anti-Saudi lobby was that they were able to plant op-eds and articles in Western media in the period after 2015. For them, the narrative was that the new Crown Prince was “destabilizing” Saudi Arabia. For them, “stability” meant the Brotherhood and anti-American and anti-Israel views. For them, “stability” was working with Iran.

They conjured up various “scandals” about Riyadh’s new line, including complaining that Riyadh’s new younger leadership had bought an expensive painting. For a group that had enjoyed the “good old days” of the 1990s, it was odd to hear them complaining of lavish spending in the Gulf, when they enjoyed the lavish spending so long as it was from Doha or others. Be that as it may, the anti-Saudi lobby had its achievements. It likely caused Riyadh to believe a conspiracy existed in the West, involving dissidents, and that Saudi Arabia had to act more forcefully.

The Abraham Accords and the close ties between Saudi Arabia and the Trump administration fed into the view that Saudi Arabia had become a partisan issue in DC. Meanwhile, the same process occurred with Israel; there was a desire in some sectors to turn Israel and Saudi Arabia into partisan issues.

Why make Israel and Saudi Arabia into a partisan issue?

This benefits those who wanted to make sure that once Trump left office that more critical voices would take a tougher line on Jerusalem and Riyadh. If you can convince enough members of Congress and officials that Israel and Saudi are somehow linked solely to one political party, then every time the other party is in charge, they will lose out.

This has an effect on the other side as well. But this partisan approach to foreign policy was not as successful as some who backed it thought it would be. The pro-Iran deal crowd and the anti-Saudi crowd are usually the same people; the anti-Israel crowd found that the incoming Biden administration didn’t want this toxic-domestic-politics embrace of foreign policy.

The Biden trip to the Middle East in mid-July is an example of the failure of the anti-Saudi lobby, the pro-Iran lobby and the anti-Israel lobby. These entwined lobbies are not all the same, but they tend to be. The same think tanks that pop up and “human rights” groups that solely focus on obsession with Israel or Saudi Arabia are very transparent in what they are doing.

The Turkey angle

At the same time, another process was playing out in Washington. Turkey also has a lobby in the West. The lobby consists of a few groups. Some are former officials who believe in a Cold War view of Ankara. They think Turkey is an ally of the West against Russia. They want Turkey armed as much as possible.

There are other pro-Turkey voices who are also pro-Brotherhood, because the ruling party of Turkey has roots in the Brotherhood. There are also those who came to Turkey’s aid via the Syrian rebellion. They dislike the Assad regime, and they dislike Iran and Hezbollah, but they believe Ankara is the best hope of the former Syrian revolution, and some of them are more sectarian, claiming Turkey is the best hope of “the Sunnis,” by which they tend to mean the Syrian rebels. The pro-Ankara voices are not always anti-Israel or anti-Saudi.

Regardless of the groups that back a strong Turkey-US relationship or believe that Ankara is against Iran and Russia – which it is not – Ankara tends to sabotage its own relations with the West. Ankara likes to meet with the leaders of Russia and Iran and threatens new invasions and ethnic cleansing of Syria, seeking to target groups the US backs, primarily Kurds. Turkey also works with extremist groups and ISIS members always seem to shelter near Turkey’s border in Syria.

As such, Turkey has found that it now faces a lot of opposition in Washington. Voices in Congress don’t want Turkey getting more F-16s. They wonder about Ankara helping Iran and Russia avoid sanctions. They also are concerned about press freedom in Turkey and the suppression of dissidents and minorities.

Turkey has also undermined NATO and threatened Greece, Cyprus, France, Israel, the UAE, Egypt, and other countries. None of this makes Turkey seem like an ally anymore. Biden had to meet with Turkey to get Finland and Sweden into NATO, but in general Ankara gets the cold shoulder.

Turkey: The Trump era vs. now

The declining stock of Ankara in Washington is in contrast to the Trump era. Turkey enjoyed close ties to the Trump administration: so close it was able to harass US officials and employees of the US embassy in Turkey; it was able to threaten US troops in Syria, target activists like Hevrin Khalaf; it was able to detain a US pastor and threaten Israel and back Hamas without much pushback.

Only in 2020 did some in the Trump administration tire of Ankara’s threats. Prior to that, Turkey’s leader had a direct line to the White House and made frequent calls to Trump. The White House decided to leave Syria twice, after calls with Erdogan, without informing allies or key members of Congress or US Central Command.

This chaos ended when Biden came into office. Turkey’s far-right pro-government media – which had been deeply anti-Biden and even hosted American far-right groups, labeled the left “Antifa” and even made a list of “Jews” in the new Biden administration – suddenly found itself forced to compromise.

Turkey’s leadership began to talk new ties and a reset with Israel. Indeed, with Benjamin Netanyahu out of office, Turkey sought out better ties. This cynical decision came as Ankara also pretended it wanted reconciliation with Greece, Egypt, the UAE, Saudi Arabia and others. Did it think that with Biden in town it would be isolated and needed Jerusalem and Riyadh to help it get F-16s?

The future of Turkey and the Biden administration

It's not clear if Ankara will achieve many results with the Biden administration, but it is clear it is trying. Turkey was emboldened in its anti-Israel antics and anti-NATO antics by its ties to the Trump administration. It felt it had a blank check to host Hamas more openly, to back extremist groups, to do ethnic cleansing of Afrin; no conflict was too high, even attacks on Armenia.

In the summer of 2020, Ankara’s antics became the most extreme, threatening war with Greece and threatening France. Israel was concerned. Turkey helped stage the media coverage of the Khashoggi story, and also used a coup attempt as an excuse to purge hundreds of thousands of officials. It cracked down on mythical “terrorists” and even attacked protesters in Washington. The whole disaster unfolded because Ankara believed it had total backing from the White House at the time. Similarly, Ankara’s leader went to the UN and compared Israel to the Nazis.

The strategies that led Ankara to confront Israel between 2016 and 2020, and which led to growing voices against Saudi Arabia in the US, are linked. Similarly, those who support the Iran deal and those who sought to prevent Israel-Gulf normalization are linked.

An Israel that was isolated from the Middle East was expected to be more compliant and dependent. As such, those who wanted an Iran deal also wanted Israel isolated so they could pressure it. Those who want Saudi Arabia jettisoned as a US partner are not necessarily the same group that wants Israel isolated; but the end result of their efforts is that if Riyadh is given the cold shoulder, which countries will anchor US policy? Will it be the Gulf states such as the UAE or Qatar, or do they want the US to leave the Middle East?

Turkey’s decision to go from belligerent threats to trying to reconcile is tied to its sense of isolation. This is a big difference from a decade or so ago when it was Israel that appeared isolated.

The overall trend is not clear. The domestic-foreign nexus of US foreign policy has led to a decision to challenge America’s historic alliances. It has also led to sectarian arguments in the US about backing the “Sunnis” and “Shi’ites.” This also leads to deep differences over how some view Israel, Saudi Arabia and other countries.

The Biden administration has pursued a traditional sense of US security policy, minus Turkey, in the region. The difference for the Biden administration is that today, unlike in the 1990s, Saudi Arabia and Israel appear to be converging on interests. For some, that tectonic shift is shocking; for others, it means the chance to anchor the US in several strong states in the region and not need to act as a shield for those countries.