Otto Frank was adamant: “Do not make a Jewish play out of it.”

He was addressing American novelist and journalist Meyer Levin who, obsessed with Anne Frank’s diary, introduced it to American audiences in the early 1950’s in a stage production called The Diary of Anne Frank.

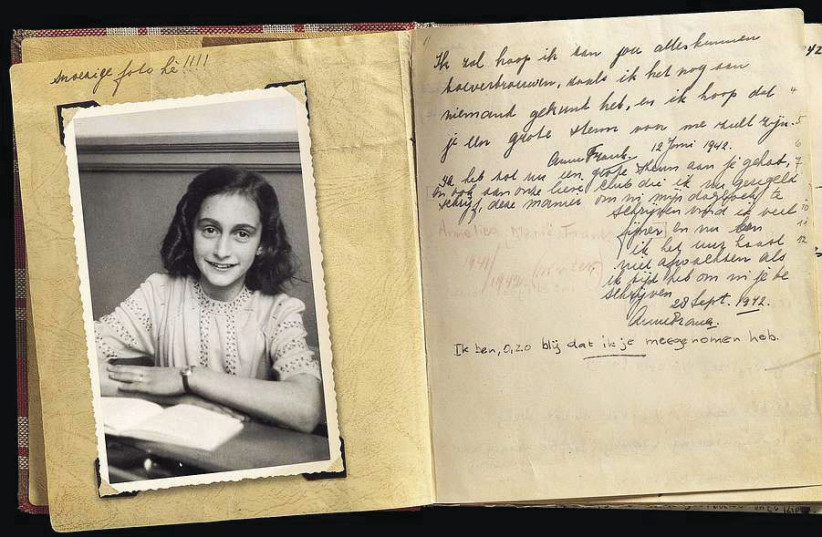

Although Anne’s diary was written while the family was hiding in the secret annex of her Amsterdam home while the city was under Nazi occupation, her bereaved father’s directive to Levin was to downplay the Jewish aspects of the story.

“As to the Jewish [issue] you are right that I do not feel the same way you do,” Otto told Levin, who had yearned to be the diary’s playwright and was taken aback by this attitude.

Otto continued: “I always said that Anne’s book is not a war-book. War is the background. It is not a Jewish book either, though Jewish sphere, sentiment and surrounding is the background. I never wanted a Jew writing an introduction for it. It is (at least here) read and understood more by Gentiles than in Jewish circles… So do not make a Jewish play out of it.”

More universal perspective, less Jewish Anne

Otto wanted the play to have a universal perspective and therefore rejected Levin’s desire to present a more Jewish Anne.

Eventually, it was the famous non-Jewish playwright couple, Albert Hackett and Frances Goodrich who created the play that was later adapted for film and more in line with Otto’s universal Anne. Both play and film were highly praised by critics.

In most of my essays, I strive to cite as many different primary and secondary sources as possible. To discuss Anne Frank’s legacy would be impossible for me without the groundbreaking work of respected historian and English professor Alvin H. Rosenfeld. His chapters on the Frank phenomenon in The End of the Holocaust (2011) must be read by anyone concerned with how – and if – the Shoah will be remembered as the worst persecution of Jews in our history.

Rosenfeld does a great service by bringing Anne Frank back to life as a Jew. He takes words from her diary that had been ignored by her father’s narrative that saw her as a generic symbol of youth triumphing with the light of hope in the face of darkness – and reintroduces an Anne who understood she was in hiding because she was a Jew. Anne was aware that Jews in Amsterdam were being captured by the Nazis and taken away and was even proud of being a Jew.

If The Diary of a Young Girl (published in English in 1952) and the play and film on which it is based were not iconic – and possibly the only source most people have of the Holocaust – it would not matter that Anne was the eternal, generic optimist. But after four decades of reading Holocaust memoirs by those who died and those who survived, I recommend an antidote to “Hope triumphs over genocide”: Read The Death Brigade (first published in 1963 under the title The Janowska Road) by Leon W. Wells. This ignored memoir of a Jewish prisoner forced to exhume and burn the corpses of Jews murdered by the Germans in Lviv (“Lvov” in Russian), Poland, is unforgettable in conveying the horror of genocide, specifically the Shoah.

Otto Frank would not have liked it.

Recently, Jews and non-Jews commemorated Anne Frank’s birthday on June 12. I will celebrate her life by using her own words from her diary entry for April 11, 1944, with a debt to Prof. Rosenfeld:

“We have been pointedly reminded that we are in hiding, that we are Jews in chains, chained to one spot, without any rights, but with a thousand duties. We, Jews, mustn’t show our feelings, must be brave and strong, must accept all inconveniences and not grumble…."

“Who has inflicted this upon us? Who has made us Jews different from all other people? Who has allowed us to suffer so terribly up till now? It is God that has made us as we are, but it will be God too, who will raise us up again. If we bear all this suffering and if there are still Jews left, when it is over, then Jews, instead of being doomed, will be held up as an example. Who knows, it might even be our religion from which the world and all peoples learn good, and for that reason and that reason only do we suffer now. We can never become just Netherlanders, or just English, or representatives of any country for that matter, we will always remain Jews, but we want to, too.”

Otto Frank endured one of the worst traumas. Yet, would his daughter Anne have agreed with his attempt to rob her of her Jewish identity and consciousness? Anne knew the Jews of Amsterdam were being deported and would all likely die. She includes this in her diary entry for October 9, 1942.

In the end, Anne was one of the 105,000 Jews murdered by the Nazis in the Netherlands. According to historian Lucy Dawidowicz in The War Against the Jews (1975) this figure comprised 75% of the Jews residing in the Netherlands before the war. Otto’s Anne is not Anne as she truly was but what he needed her to be. The vision we have is Otto’s, not Anne’s.

To condemn Otto Frank is painful but necessary.

A victim of the Great Depression of 1929, he had been a failing businessman in Frankfurt who moved and his family to South Amsterdam, the home of many German-Jewish refugees in the 1930’s. In Amsterdam he sold pectin (a natural gelling agent used for jams and jellies) and later spices used in the making of sausages.

“The enterprise was a comedown for a man who had been a reasonably prosperous private banker in the 1920’s” writes historian Bernard Wasserstein in On the Eve (2012).

I do not know what his religious views were – he was born a Liberal German Jew – or if he belonged to a synagogue, but the Holocaust, the years hiding, and the Nazi destruction of his family were a nightmare come to life. His daughter’s diary was, for him, an enduring symbol of hope in the face of inhumanity. That the Franks were Jews was not important.

“Who knows how anyone would feel about being a Jew after enduring such suffering?” he asks.

But one thing is certain and even Otto could not change it: Anne Frank was a Jew.

The writer is a rabbi, essayist, and lecturer in West Palm Beach, Florida.