Physicists are hardly natural film material, but this one – a charismatic genius, flamboyant adulterer, political casualty, and generator of history’s biggest blast – offered all the makings of a box-office hit, which Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer indeed became.

Widely expected to win this month’s Best Picture award, the biopic about “the father of the atomic bomb” delivers everything the Oscars were created to salute: a captivating screenplay that interweaves dramatic events with sharp dialogue; dazzling cinematography that interplays color segments and black-and-white scenes; and impeccable acting led by Cillian Murphy as physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer; Matt Damon as Leslie Groves, the Manhattan Project’s no-nonsense military head; and Robert Downey Jr. as government official Lewis Strauss.

The atomic bomb was a historical landmark in multiple ways: It ended World War II, revolutionized energy production, sparked the Cold War, and opened a moral Pandora’s box, as mankind was handed a tool for its self-destruction.

However, these are not this film’s subject, only its context. The subject is Oppenheimer’s life, a journey from supreme success and popularity to derailment and humiliation through intellectual inspiration, scientific leadership, and mental hubris.

This focus is why Nolan avoided showing the bomb’s carnage and massacre in Japan, and that is why he dramatized its initial detonation in New Mexico. The film’s hero did not experience, much less plan, what his bomb did in Japan, but he sure did plan, experience, and absorb the impact of its initial blast.

The same goes for Jewish history’s place in all this, which the film also keeps narrow, with the same narrative legitimacy and cinematic rationale. Yet the Manhattan Project is in many ways a profoundly Jewish story, a Jewish saga that for us Israelis is relevant any time, but doubly so in these days of awe.

Jewish invention

THE MANHATTAN Project’s first Jewish dimension is personal. Six of its eight leading scientists, including Oppenheimer, were Jews, as were hundreds of other participants.

The second dimension is political, namely, the two circumstances under which most of the project’s Jews came to join it: First, the political assault that made Germany’s Jewish scientists lose their jobs; and then the military assault that made America seek the bomb and launch the project that deployed many of the anti-Jewish assault’s victims.

Nobel laureate James Franck, for instance, was expelled as a Jew in 1933 from the University of Gottingen. Danish-Jewish physicist Niels Bohr, also a Nobel laureate, fled Copenhagen on a fishing boat. Fellow Nobel laureate Enrico Fermi, the Italian physicist who conducted the first controlled nuclear chain reaction, fled Europe because his wife was Jewish.

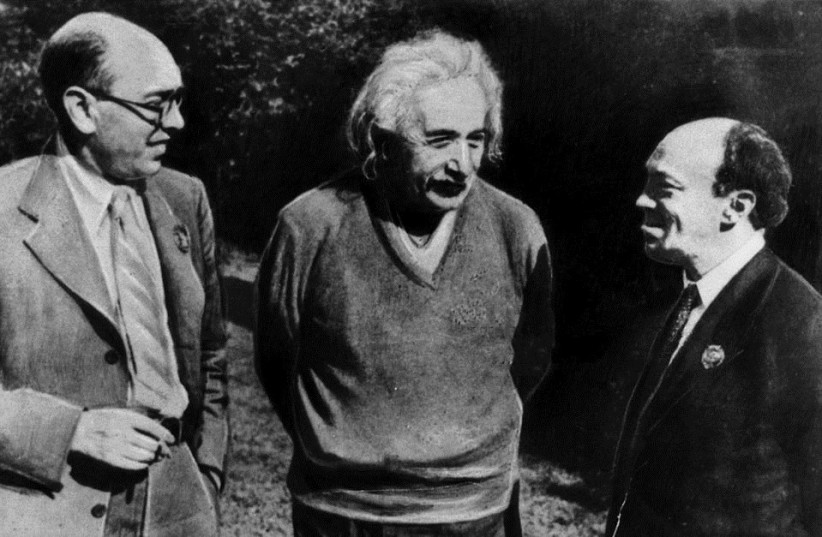

Hungarian-Jewish physicist Leo Szilard, who conceived the nuclear chain reaction, fled Europe earlier and persuaded Albert Einstein to write Franklin Roosevelt the letter that made the president green-light the Manhattan Project.

The disproportionate Jewish share in the bomb’s creation has long been a matter of curiosity. Some see it as a reflection of the so-called Jewish genius, a term that implies Jews are genetically smart. That’s of course impossible, considering the number of Jewish idiots each of us knows all too well.

Instead, as this writer has argued elsewhere, Jewish excellence is a result of Jewish heritage, a culture that cultivated scholarship, and admiration for the scholar, since antiquity. The exceptional role played by Jews in creating the bomb is therefore not surprising. The incredible thing about this tale is the substance of what those smart Jews created, why they created it, what they did once they created it, and what it all means.

OPPENHEIMER AND his colleagues created what the Jews had not wielded since the Roman era: power.

Ironically, Jews created the biggest explosion since Creation at the very time when millions of other Jews were being massacred with impunity. The bomb’s Jewish scientists were not massacred, but they too were mostly victims of Jewish weakness, and those who were not its direct victims – like the American-born Oppenheimer – were moved to act because of what was done to those who were.

Even more curiously, once the bomb was operable many of its Jewish creators, led by Szilard and Franck, petitioned president Harry Truman not to drop the bomb on Japan.

“In nuclear weapons,” they wrote, “we have something entirely new in order of magnitude of destructive power.”

Though they were assimilated Jews only minimally acquainted with Jewish heritage, the petitioners acted as if they had somehow been imbued with the biblical prophets’ abhorrence of war and quest for universal peace.

To make things even more paradoxical, the petitioners failed to prevent political power’s usage of the physical power they created because in wartime America, just like in prewar Europe, they lacked what their invention multiplied and their effort begged: power.

No tale in the history of the Jews, then, encapsulated more forcefully the Jews’ troubled relationship with power; the delusion that powerless people can impose moral power on political power.

That is how a set of Jews who helped create a physical power more powerful than any mankind ever created were also the embodiment of Jewish weakness; Jews who first were robbed with impunity of their jobs, property, and homelands due to their Jewishness, and then saw helplessly from America their relatives’ mass murder in Europe.

The Manhattan Project thus demonstrated better than any other episode in Jewish annals both the feasibility of Jewish power’s creation and the tragedy of its absence.

Now, as the restoration and activation of Jewish power unsettles new antisemites, our message to them is that we prefer to be asked, as they ask us daily, “Why are you fighting?” than to be asked what Kitty Oppenheimer asks her politically embattled husband, the atomic bomb’s Jewish father: “Why won’t you fight?”

www.MiddleIsrael.net

The writer, a Hartman Institute fellow, is the author of the bestselling Mitzad Ha’ivelet Ha’yehudi (The Jewish March of Folly, Yediot Sefarim, 2019), a revisionist history of the Jewish people’s political leadership.