Other research companies, research departments, individual scholars and think tanks did not wait for government-level memoranda of understandings and bureaucratic arrangements. From the moment the first normalization intentions were published, a flow of emails spread across institutions and individuals in both countries in an attempt to find matching research partners. Initiatives by Israeli researchers often elicited positive responses, while fewer initiatives were forthcoming from the Gulf to Israel. This kind of enthusiasm and motivation was not seen when the Egyptian, the Sudanese, and even the Norwegian research community were addressed, at least from the Israeli side. While this trend illustrates the warmth of the burgeoning relationship, the nuances in these ties reveal their genuine nature.

So far, these encounters have exposed significant differences between the Israeli and Gulf systems of higher education, requiring awareness and attention, and possibly some adaptations.

A top-down approach

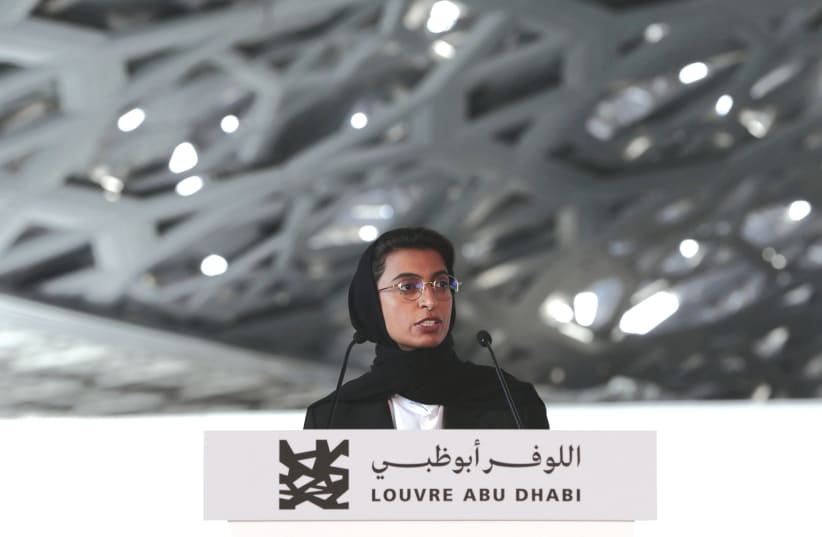

The Emirati universities and research institutions are integrated into official governmental mechanisms at varying levels of ties and commitment. For example, the presidents of public (governmental) universities are generally cabinet ministers as well. Culture Minister Noura Al Kaabi is also the president of Zayed University; Minister of State Zaki Nusseibeh is the chancellor of UAE University. Even when the role is purely symbolic, it illustrates the affinity between the government and the academic sectors.

These structural and cultural characteristics directly affect the ways research ties could develop. Additionally, traditional barriers have not yet been removed. In this interim period between the signing of the Abraham Accords and the full realization of collaborations, there is still considerable hesitation. On the one hand, the individual researcher based in the UAE is relatively independent in conducting joint projects and maintaining research ties with Israeli scholars. For the most part, their collaboration might unofficially impact their social status in the department or university spheres.

On the other hand, reaching out to the faculty or university administration level is far more challenging, as the higher administration levels await formal authorization. Until bilateral ministerial agreements on higher education will be achieved, most of the institutional initiatives from Israel will encounter significant obstacles. Within this state of affairs, some progress was achieved in very few cases, such as the MoU between the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot and The Mohamed bin Zayed University of Artificial Intelligence in Abu Dhabi.

Mapping research institutions in the UAE and Bahrain

The UAE and Bahrain have both public and private institutions of higher learning. Mostly, Emirati nationals are eligible to study at the UAE’s public universities, while most of the faculty are international. Studies are conducted separately for men and women. Women constitute a distinct majority in the UAE and in Bahrain’s public universities, whereas most of those who go to study abroad are men.

The private facilities include universities, colleges and research institutions, some locally owned and others branches of international universities. Absurdly, perhaps, the American and European university branches in the UAE are not as free to initiate ties with Israel as the Emirati ones. The reason is that their administrations, naturally, are not as closely affiliated with the local leadership as are government or privately owned local universities and therefore their waiting period for a green light is longer.

In other words, the management of public universities or locally owned, private ones would probably feel more comfortable making some decisions independently, whereas NYU Abu Dhabi and Sorbonne Abu Dhabi will wait for official government approval. Within the private research sector, think tanks seem to provide fertile ground for high-profile ties with Israeli research and policy institutes. This stems from their smaller size and relatively independent standing due to their affiliation with government leadership.

Fewer Oriental scholars, more scientists

In the past, the image of Israeli research ties with the Arab world was associated mainly with Islamic studies. The Abraham Accords change this paradigm from research on the Middle East to research with Middle Eastern states. The launching of research opportunities with the Gulf countries to Israeli scholars opens broad mutual research interests. Humanities in the Gulf states are relatively marginalized, with most attention devoted to applied sciences, such as management, environmental studies, law, cyber, computers and digital sciences, artificial intelligence, engineering, economics and the space industry.

There was good reason that the first official collaboration between Israeli and Emirati research centers was in the context of the coronavirus in a joint effort to develop vaccines. Beyond the popularity of these research fields in the Arab Gulf states, the move highlighted the UAE’s ambition to position itself as a scientifically advanced state.

International affiliation

Unlike Israeli institutions of higher education, studies in the UAE’s universities and colleges are conducted in English. As mentioned, most of the teaching and research faculty consist of foreign nationals, which affords a diverse scientific environment with abundant research approaches.

The dominant international orientation in the UAE, Bahrain and other Gulf states is discernible not only in their domestic institutions but also in their outreach abroad. Most talented students with top grades will eventually study in the West, returning home with vast knowledge, diverse ideas and cultural influences. Usually, these students are granted government scholarships, and in most cases return to their home countries upon their graduation.

Furthermore, the Gulf states invest heavily in international cooperation with various foreign research institutions. The endeavors to integrate into the global research arena are also reflected in the formation of research centers abroad, aligned to their research doctrines and interests. Therefore, scientific collaborations with Israel, even on the institutional level, will be among many others that these states conduct.

Researching research

The academic and political culture of the UAE and Bahrain are very different from the West’s, and despite the abundant presence of international scholars, the local system creates unique conditions and characteristics. As a result, in attempting to advance scientific and research ties with these states, we must do what we do best – study and research the higher education system in the Gulf to understand it better before approaching it.

Dr. Moran Zaga is a specialist on the UAE and boundaries in the Middle East. She is a policy fellow at Mitvim–The Israeli Institute for Regional Foreign Policies and a researcher at the University of Haifa and the University of Chicago.