Stars rich in metals needed for the creation of planets and ultimately life may actually, and somewhat ironically, be less suitable for hosting alien life compared to metal-poor stars, a new study has found.

The findings of this study were published in the peer-reviewed academic journal Nature Communications.

These findings go against common preconceptions in astrophysics since metal-poor stars blast far more intense ultraviolet radiation.

As a result, the findings can point scientists in a new direction when looking for extraterrestrial life.

That's so metal! A stellar study on finding alien life by metal-poor stars

The first thing to note about metals in this study is that in astrophysics, the word "metal" does not exclusively refer to the different elements classified as metals on the periodic table. Rather, "metal" is a label that can be used to describe literally any element heavier than hydrogen and helium. In addition, and this is by no means a coincidence, hydrogen and helium are the two lightest elements.

The reason for this classification is because of the sheer abundance of hydrogen and helium compared to everything else. But in addition, it also is due to the fact that the heavier elements are also more complex than hydrogen and helium.

Now that that's out of the way, let's talk stars.

At first glance, stars seem to be just big balls of flaming gas and light. While this is technically true, there is far more inside it than just gas. The star works to process its materials to create new complex elements.

The planets that form around these stars are formed due to the massive rings of dust and minerals formed, accreting into each other to eventually form worlds.

One might think being rich in metals is crucial to the planet-forming process, and that would be the issue at the heart of the study, but that actually isn't the issue here.

The real issue is ultraviolet (UV) radiation. This type of radiation can be very powerful and damaging. In some ways, this makes sense – it has long been hypothesized that intense UV radiation exposure on a young planet may very well be essential for life to start forming.

However, it can also be so strong that it would essentially kill any life on the planet.

Consider, for a moment, our own sun. The amount of UV radiation the Sun emits is far greater than what living beings should be able to withstand, meaning that in theory, life on Earth is completely impossible.

Of course, it has happened, so why and how?

Atmosphere is everything

This is where the atmosphere comes into play. Earth's atmosphere rich in oxygen absorbs most of the UV radiation.

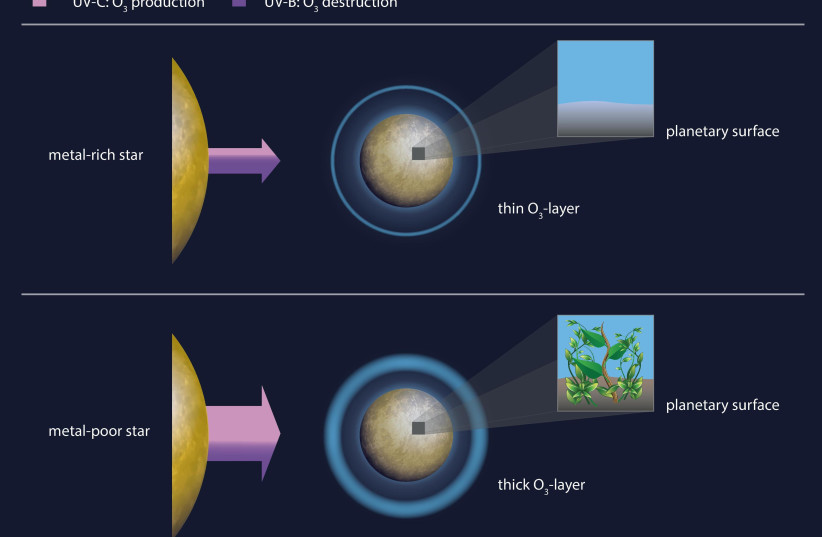

Interestingly, low UV radiation from a star can lead to a planet having low ozone levels, which in turn means low UV radiation protection.

So how does this involve metals?

A star's metallicity impacts the level of UV radiation it emits. As a general rule, the more metal-rich a star is, the less UV radiation it emits.

Does the level of metallicity impact UV radiation as well as UV shielding?

This is what the study sought to find out.

To do this, the research team, led by Anna Shapiro, ran a simulation with a bunch of hypothetical Earth-like planets, each within the habitable zones of their own stars. These stars ranged in terms of metallicity, some being metal-rich and others being metal-poor.

The question was not which stars emitted more UV radiation, but rather which planets were better shielded from UV radiation.

The result was that, surprisingly, it was the planets around metal-poor stars. This is because while the metal-rich stars emit less UV radiation, their planets end up with weaker shielding.

So what does this mean going forward?

The major result of this study is that is now an even more narrow range of stars to look at for finding alien life. With this newfound information, it may be possible to better limit the parameters of further research to specifically detect worlds that could host such life on their surface.

This is important for the upcoming PLAnetary Transits and Oscillations (PLATO) of stars space telescope, which has the main objective of finding Earth-like planets.

It should be noted though, that not all scientists agree with the central premise of this entire study: That life can only exist in the conditions humanity itself requires.

According to Peter Worden, executive director of the Breakthrough Initiatives, there is no reason to assume that life can't or doesn't exist in environments that drastically differ from that of Earth's surrounding our Sun.

"Many experts believe life can and does exist under ice crusts in our own outer solar system. Some measurements suggest life exists in the hostile upper atmosphere of Venus," Worden explained to The Jerusalem Post back in 2022.

"The truth is we don’t know much about how life forms or where it can develop."