It was May 1938, just two months after Nazi Germany had annexed the neighboring country of Austria, the German regime’s first act of territorial aggression known as the Anschluss. Almost overnight, Austrian and German Nazis carried out the Nazification of all aspects of Austrian life. There were immediate antisemitic actions – Jews forced from all their positions and arrested if they didn’t surrender their property.

That May day, according to an account published by the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, American tourist Helen Baker was visiting the main cemetery in Vienna, looking for Beethoven’s gravesite. As she walked through the Jewish section, she noticed a row of 21 freshly dug graves along the perimeter of the cemetery. She later learned they were the graves of Jews who had committed suicide following the Anschluss. “One doctor…we know was called for 60 suicides,” she wrote at the time.

Among that wave of Jewish suicides was Frieda Flesch, the mother of Israeli clinical psychologist Ruth Sitton, who was then only one year old. Her father, Julius Flesch, an engineer, was arrested and sent to the Dachau concentration camp in southern Germany. Little Ruth was taken in by relatives.

The story of Ruth Sitton

Julius (together with the famous Austrian-born psychologist and author Bruno Bettelheim) was released from Dachau in 1939 and returned to Vienna on condition that he leave the country with no possessions. Before the Third Reich initiated its plan of mass extermination in 1941, before the Wansee Conference of 1942 which established the final solution, German and Austrian Jews were “encouraged” to emigrate.

Jews stood in long lines night and day seeking German exit visas, in exchange for which they had to turn over all their possessions; then again to appeal to foreign embassies to request immigration visas. Most of the foreign consulates denied Jews’ requests.

How did the Nazis help Jews immigrate to Palestine?

Julius and Ruth would eventually be able to leave Vienna on ships bound for Palestine, thanks to the intervention of Adolf Eichmann.

Relating this astonishing story today in her home in the northern Negev town of Omer, 86-year-old Dr. Ruth Sitton describes the chance meeting between her father and the Nazi war criminal who would become a symbol of the hideousness of Hitler’s Germany.

It’s hard to believe today, but for a brief period the Nazis worked together with emissaries of Aliyah Bet, the clandestine immigration of Jews to British-controlled Palestine. In 1939, Eichmann established the Central Agency for Jewish Emigration in Vienna administered by the Gestapo. He appointed Austrian Jewish financier Berthold Storfer to work with Aliyah Bet to organize the passage of Jews to Palestine. (Storfer, a controversial figure considered a collaborator, was later murdered in Auschwitz.) He chartered three ships to transport approximately 3,600 Jewish refugees from Vienna, Prague, Brno, Berlin, Munich and Danzig to British-administered Palestine – despite, or more likely because, it violated Britain’s restrictive Jewish immigration policy.

“Father tried to book a transport to Palestine, but he was notified that they wouldn’t take any more children because of an outbreak of a children’s disease on an earlier ship,” Ruth relates. Her father was working at the Vienna Jewish Community Emigration Office, which was next door to the Gestapo headquarters. “He met Eichmann in the corridor, who asked him, ‘Why are you still here?’ When my father explained that he was waiting for the ship, but they wouldn’t take his daughter and he wouldn’t go without her, Eichmann made a call to the Aliyah Bet people and instructed them to take this man and his daughter.”

“He met Eichmann in the corridor, who asked him, ‘Why are you still here?’ When my father explained that he was waiting for the ship, but they wouldn’t take his daughter and he wouldn’t go without her, Eichmann made a call to the Aliyah Bet people and instructed them to take this man and his daughter.”

Ruth Sitton

Ruth’s two teenage brothers had, separately, already left Vienna. The younger brother, Ephraim Fritz, was one of 50 Austrian children accepted in 1938 to the Mossad Ahava (love in Hebrew) boarding school in Kiryat Bialik in Palestine.

The older brother Zvi Leopold had left with a group of young Jews on an earlier Aliyah Bet commissioned ship, also headed for Palestine. But when the Danube River froze over, the group disembarked to a camp in the Yugoslav River port of Kladovo to wait for another ship. When the Germans invaded Yugoslavia in 1941, they caught them, killing nearly all the men and women, including Ruth’s brother.

On September 3, 1940 (a year after the German invasion of Poland, marking the beginning of WW2), bearing Third Reich passports stamped with pretend visas to Paraguay, Ruth and her father boarded the small ship in Vienna which would take them all the way down the Danube River to the Black Sea – it would be the last ship carrying Jews to leave Vienna. On September 12, Yom Kippur, they reached the Romanian port of Tulcea.

The refugees from Vienna were allocated places on the SS Atlantic, one of the three-ship convoy bound for Palestine. Engine and other technical problems meant they departed Tulcea a week or so later than the other two ships – the SS Pacific and the SS Milos. That delay would result in another extraordinary life-saving incident. Though some of the Jewish refugees on the three ships succumbed to typhus and other diseases, most survived the long journey to Haifa, only to be refused entry to Palestine. The British colonial authorities enforced the recently passed White Paper of 1939, which restricted immigration of Jews to British Mandate Palestine, and ordered that the group be sent to the British colony of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean.

The passengers of the Milos and the Pacific, who had arrived in Haifa earlier than the Atlantic, were forcibly transferred to another ship called the Patria, which would take them to Mauritius.“We arrived after the two other ships had reached Haifa and the British had already moved everyone to the Patria. Then they started to move us too in small boats,” Ruth relates. “I remember sitting on our luggage in that small boat taking us from the Atlantic to the Patria. Suddenly my father realized that he’d left a rucksack on the ship and went back to the Atlantic to get it; but when he tried to return, he was stopped by a soldier. He said, ‘Either you let me back on the boat or you let my daughter come to me.’ I remember the lady behind me saying ‘I’ll look after her; take the next boat.’ But he refused. In the end, they gave me back to my father, leaving everything in the boat.”

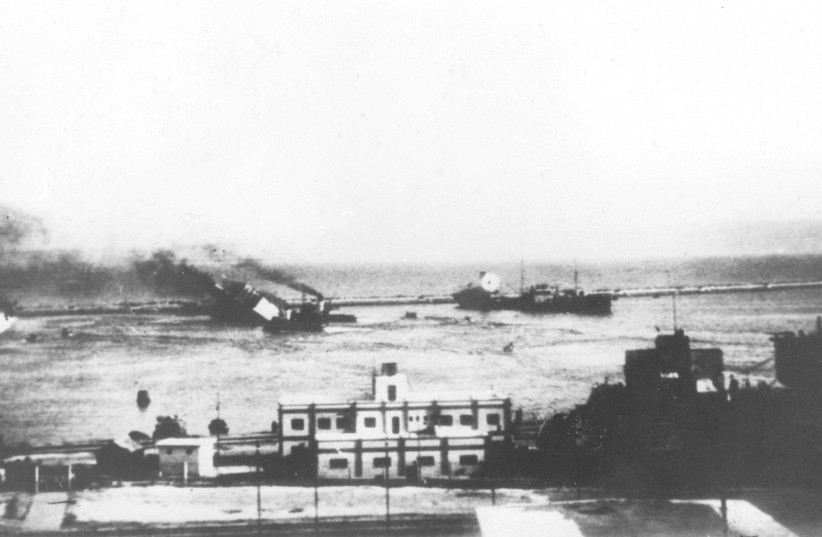

As they were standing on the steps leading down from the ship waiting for the next boat, she says, “My father noticed that the Patria was listing severely to the side. He said he didn’t understand why this was happening to a big ship.” Although they hadn’t heard the explosion, they later discovered that the ship had been blown up by the Hagana, the Jewish underground military organization, which had decided to plant a bomb on board the ship in order to prevent the planned deportation. The ship sank almost immediately, causing the death of more than 260 Jewish refugees who were below deck. (The Hagana later maintained that its aim was only to disable the engine and force the disembarkation to Haifa. They grossly miscalculated the amount of explosives used or how rundown the old ship was, which resulted in the catastrophe.)

The survivors of the Patria and the remaining refugees on the Atlantic were all taken ashore to Atlit, a British detention camp, 12 miles south of Haifa, after first going through disinfection and showers. The British authorities ruled that all the Patria survivors would be permitted to remain in Palestine.

The camps in Atlit were divided into those who were able to stay and those who would be deported to Mauritius. On December 9, 1940, some 1,580 of the Atlantic passengers were forcibly removed from Atlit, placed onto two Dutch ships and deported to Mauritius.

After a 17-day journey, the refugees arrived at the harbor of Port Louis, the capital of the British colony of Mauritius, and were transferred to Beau Bassin Prison, which had been converted to an internment camp for the purposes of housing the group. This would be their home until the end of the war in 1945.

“When we first arrived, the women’s camp had not been set up yet, so everyone was together; but when the accommodations on the women’s side were constructed, men and women were separated,” recalls Ruth. “All the children under 14 went with the women. My father was holding me in his arms when the guard said I had to go to the women’s section. The British Army guards were Indian, tall men wearing turbans. I screamed. I still can hear that scream in my ears,” she recounts.

She was given a bed in one of the barracks. Without a parent, she was more or less left to her own devices. She remembers a teenage girl named Margot who would tell her stories at night. Later, her father was given the job of medical orderly and was allowed to enter the women’s camp. “He earned a little money this way and could pay women to look after me. The wives of the British officers somehow took a liking to me. I was a well-behaved little orphan girl. I could even curtsy.”

After about a year in the camp, a German language school was set up, as well as a clinic. Some of the internees were physicians and formed part of the medical staff.

“For serious illnesses or operations, we were taken to a hospital in the city. Everyone had malaria. My father was so ill with malaria, that it affected his liver. When we came back to Palestine, he was transferred to hospital immediately,” she says.

Finally entering Palestine

The refugees were released in May 1945 and boarded a ship for Palestine in August. “The British allowed them to enter Palestine because there was a lot of international pressure, especially when what happened in Europe became known,” Ruth explains. Some of the detainees chose to return to Europe and disembarked in the port in Gaza.

Ruth, then eight years old, remembers their arrival in Haifa. She was sent to the Mossad Ahava boarding school in Kiryat Bialik (today Kfar Ahava) near Haifa. Most of the residents were still German-speaking, but the schools taught in Hebrew, which she quickly learned. Her father recovered from malaria and was given a small apartment in Kiryat Haim, which he could share with her brother Ephraim, who had enlisted with the British Army in 1942 and was based in Alexandria. In 1948, he joined the new Israeli Army in the War of Independence. He was killed while fighting in the Galilee. “My father was given a kiosk on the Carmel in Haifa, but he never recovered. He was a broken man.”

Ruth would go on to finish high school and was accepted at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. “I wanted to be a psychiatrist, but there was no way I could have gone to medical school at that time. Eventually I became a clinical psychologist. I always liked working with children and would eventually work mainly with children,” she says.

Ruth married botanist and biochemist Dov Sitton in 1960. They have two children and five grandchildren and have lived for decades in the southern town of Omer, near Beersheba. She still works as a psychologist.

What has been the enduring effect of her extraordinary life experience on her approach to helping her patients? Ruth’s reply is immediate. “As a child, the experience I had in Ahava was really the most influential. The main thing, whether children or adults, is having empathy, compassion and respect towards the person sitting opposite you.” ■