Males in general, and conservative religious groups in particular, have long claimed that women should stay at home and take care of the family and the home while the male role is to hunt.

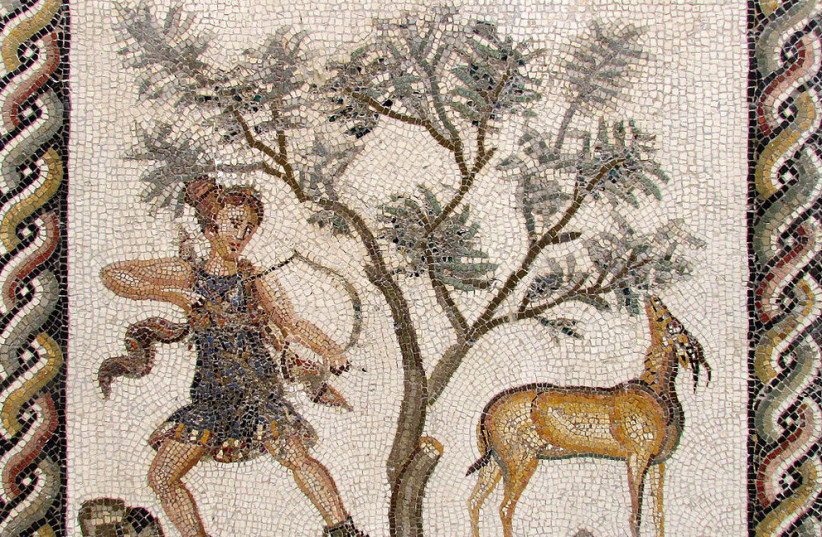

But it turns out that despite this axiom, in ancient times, females went out hunting, even with dogs, for prey of all kinds and didn’t stay in the kitchen.

Now, researchers in Seattle, Washington – Dr. Abigail Anderson, Sophia Chilczuk, Kaylie Nelson, Roxanne Ruther, and Cara Wall-Scheffler – have published “The Myth of Man the Hunter: Women’s contribution to the hunt across ethnographic contexts” in the prestigious journal PLOS ONE.

The myths have long persisted. “Women get pregnant, have to breastfeed, take care of children, how will they be able to hunt? They are weaker, smaller, and this does not suit their less aggressive nature,” wrote the American ethno-archaeologist and anthropologist Brian Douglas in 1981.

Psychologists have also argued that the feminine nature has been shaped by these roles during evolution, that women evolved to take care of and care for others, to pay attention to details and to be quiet and reserved, while male hunters had traits such as seeking adventure, assertiveness, and an attraction to battles and competition. These claims spread to the general public and influenced many people, including politicians and policymakers.

The biblical narrative of God creating the woman from the rib of the man so that she would be a helpmate for him also promoted the idea that the man is the hunter and the woman is the gatherer and lowered women’s status.

But what if these ideas were based on false assumptions and were not true?

Were women hunters too?

In 2020, an article was published by University of Nevada anthropologist Marin Pilloud who detailed the findings from a 9,000-year-old tomb in Peru. Next to the bones of a young woman, 24 stone tools including knives and spearheads were buried in the grave. Such tools are used by hunters, and are often buried together with them. “If those tools were found next to a man's skeleton, there would be no question – it was clear that he was a hunter.” The researchers agreed with her, and concluded that the ancient woman was also a hunter.

They were not satisfied with this one case, but reviewed the literature concerning ancient graves in America and discovered that the Peru hunter is not a single example. “We saw that men and women have about the same chance of being buried with tools used for hunting large animals,” said University of Maryland anthropological archaeologist Dr. Randy Haas, who led the study.

The sexual division of labor among human foraging populations has typically been recognized as involving males as hunters and females as gatherers. Recent archeological research has questioned this paradigm with evidence that females hunted (and went to war) throughout the Homo sapiens lineage, though many of these authors assert the

The University of Nevada research gleans data from across the ethnographic literature to investigate the prevalence of women hunting in foraging societies in more recent times. Evidence from the past 100 years supports archaeological finds from the Holocene that women from a broad range of cultures intentionally hunt for subsistence. These results aim to shift the male-hunter female-gatherer paradigm to account for the significant role females have in hunting, thus dramatically shifting stereotypes of labor, as well as mobility.

In 2017, a well-known burial in Sweden revealed an individual alongside weapons and equipment associated with high-ranking Viking warriors. The human was assumed to be male due to the historical interpretation of the prevalence of male warriors, but genomics confirmed that it was a female. In addition, archaeologists discovered a 2,500-year-old burial site that contained four females associated with weapons and warrior equipment. The age of the females ranged from 12 or 13 years old to 40 to 50 who were believed to be a part of the nomadic group known as Scythians. The women were warriors in their culture as supported by the fact that one-third of the females in this society were buried with weapons. The Seattle team suggested that the majority – more than half – of hunter-gatherer communities do expect females to contribute to hunting strategies.

“Data used for this study included reports on what, when, and how hunting occurred in the cultural group. Given that there is a difference between the phrase ‘women went hunting’ and ‘women accompanied the hunters’ it should be noted that we were looking for phrases along the lines of ‘women were hunting’ or ‘women killed animals,’ not references to the idea that women might be accompanying men “only” to carry the kills home, though obviously this does happen as well,” they wrote.

The type of game hunted was defined by the relative size of the prey and the hunting toolkit that was used. For example, when looking at the Tiwi society of Australia, a study reported that Tiwi women regularly hunted small animals while the hunting of large game was a man’s activity, suggesting that women were involved in hunting small game only.

Accounts of the Matses from the Amazon state that the women would strike their prey with large sticks and machetes, which would account for large game whereas other societies had documentation of small digging sticks or the killing of rodents, suggesting the prevalence of small game hunting. The prevalence of women hunting with children and dogs was also recorded and analyzed based on statements in the literature.

They concluded that there is sufficient evidence to warrant the conclusion that women in foraging societies across the world participated in hunting during more recent time periods, a finding that makes sense given women’s general morphology and physiology. “The prevalence of data on women hunting directly opposes the common belief that women exclusively gather while men exclusively hunt, and further, that the implicit sexual division of labor of ‘hunter/gatherer’ is misapplied. The data suggest that females not only prepare to hunt and actively pursue game but also that they are skilled in the practice.”

Why do we only know now that women hunted?

Why did it take so long to discover the fact that women often participated in hunting?

After all, the researchers did not make new observations but simply collected evidence from anthropological studies conducted in the past. “The biases we all have when we look at the data really affect the outcome,” Wall-Sheffler asserted.

“I hope people will look again at some of the data we already have to see what new questions they can answer.”