A Tel Aviv University (TAU) study has revealed how tumor cells create temporary formations to evade immunotherapy and subsequently cause a relapse of the malignant growth.

These findings provide a novel theory as to how tumor cells avoid destruction by the immune system. They could also promote the development of treatments that combine immunotherapy with the timed inhibition of relevant signaling pathways in tumor cells.

“Cancer immunotherapy harnesses the body’s immune system to fight cancer. Despite its remarkable success, the majority of patients who receive immunotherapy will see their tumors only shrinking in size temporarily before returning, and these relapsed tumors will likely be resistant to immunotherapy treatment,” said first author Amit Gutwillig. Gutwillig was a doctoral student at TAU’s Carmi Lab at the time the study was carried out and is now a senior researcher at Nucleai, a leading Tel Aviv company involved in the spatial biology revolution in precision medicine.

“Cancer immunotherapy harnesses the body’s immune system to fight cancer. Despite its remarkable success, the majority of patients who receive immunotherapy will see their tumors only shrinking in size temporarily before returning, and these relapsed tumors will likely be resistant to immunotherapy treatment.”

Study author Amit Gutwillig

The research was just published on the peer-reviewed eLife website under the title “Transient cell-in-cell formation underlies tumor relapse and resistance to immunotherapy.”

The editor of the journal wrote, “This is a timely and important study that describes a new potential mechanism of resistance to immune checkpoint blockade. Not only does this have significant implications for cancer immunotherapy, but it could extend to other immunological malignancies as well.”

“This is a timely and important study that describes a new potential mechanism of resistance to immune checkpoint blockade. Not only does this have significant implications for cancer immunotherapy, but it could extend to other immunological malignancies as well.”

eLife journal editor

Relapse after immunotherapy

To identify how tumors relapse after immunotherapy, Dr. Yaron Carmi and his team in the pathology department at TAU’s Sackler Faculty of Medicine began by comparing the genetic sequences of whole genomes in primary and relapsed tumors in the same patient. Their analysis suggested that relapsed tumors do not change dramatically following immunotherapy.

Next, the team studied this process in breast cancer and melanoma (the most dangerous type of skin cancer), using mouse models in which immunotherapy-resistant tumors had relapsed. They gave the mice cells from treated tumors and allowed these cells to reach a palpable size. The team found that the cells were equally susceptible to the same immunotherapy approach as the parent tumor, although they relapsed sooner.

What did the researchers do next?

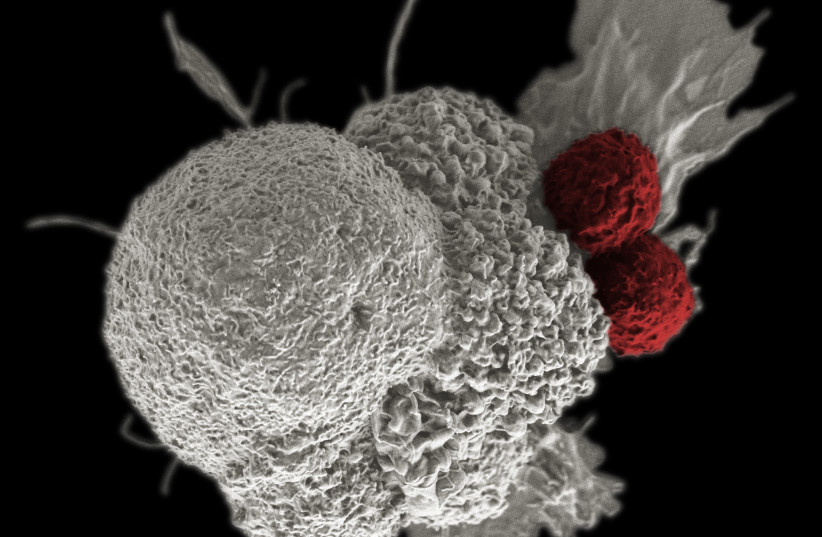

To better characterize the tumor cells that survived in mice following immunotherapy, the researchers isolated and studied the live tumor cells. They found that most of the cells responded to the presence of T cells – a type of immune cell that targets foreign particles – by organizing into temporary formations. These were made up of clusters of several tumor cell nuclei that are surrounded by a single, multilayered membrane and a meshwork of cortical actin filaments. The inner cell of the formation was dense and appeared to be compacted within another cell.

To show that this result was not due to the isolation of the melanoma cells, the team also analyzed tumors with fluorescently labeled cell nuclei and membranes. They found that the cell-in-cell formation was more prevalent in immunotherapy-treated tumors, especially in sites associated with tumor cell death. Further analysis showed that about half of the tumor cells that survived immunotherapy were arranged in the cell-in-cell formation. Over time, these cells returned to a single-cell state, with similar structural features to those of the parental cell line.

What about humans?

The team next tested whether this phenomenon occurs in human cancers. To do this, they incubated tumor cell lines with pre-activated T cells from healthy donors. They discovered that the vast majority of breast, colon and melanoma tumor cells that survived T-cell killing organized into the cell-in-cell structure. A three-day observation of T cells interacting with tumor cells showed that these structures were dynamic, with individual tumor cells constantly forming and disseminating from the structure.

“This previously unknown mechanism of tumor resistance highlights a current limitation of immunotherapy. Over the past decade many clinical studies have used immunotherapy followed by chemotherapy – but our findings suggest that timed inhibition of relevant signaling pathways needs to occur alongside immunotherapy to prevent the tumor becoming resistant to subsequent treatments.”

Dr. Yaron Carmi

Finally, they tested the clinical relevance of this discovery by analyzing cancerous tissues from multiple organs of four stage 4 melanoma patients. These patients were undergoing surgical removal of primary and metastatic lymph nodes that had spread from the primary tumor. The researchers found that in all four patients, the cell-in-cell formation was highly abundant in the T-cell zone of the draining lymph nodes, but not in the primary tumors. In a patient with untreated recurrent melanoma, most of the cells in the primary tumor were single cells, whereas the recurrent tumors had an abundance of the cell-in-cell formations.

“This previously unknown mechanism of tumor resistance highlights a current limitation of immunotherapy,” concluded Carmi. “Over the past decade, many clinical studies have used immunotherapy followed by chemotherapy – but our findings suggest that timed inhibition of relevant signaling pathways needs to occur alongside immunotherapy to prevent the tumor becoming resistant to subsequent treatments.”