I started covering diplomacy for The Jerusalem Post almost four years ago with a trip to Lisbon, where Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu was meeting with then-secretary of state Mike Pompeo.

Netanyahu and then-president of the US Donald Trump seemed like best buddies. The big topics of the day were American “maximum pressure” sanctions on Iran and a possible defense pact between Israel and the US.

Now, as I depart my role as diplomatic correspondent, the situation is almost the polar opposite: US President Joe Biden still hasn’t met with Netanyahu, his administration is making concessions to Iran and not enforcing sanctions, and there’s talk about a US-Saudi defense pact.

Of course, that’s far from a complete picture of the dramatic events in the world and Israel’s standing in it over the course of the past four years.

What are some of the factors that will forever change Israel's future?

First, there was the COVID-19 pandemic that shut much of the world down. Israel became the “vaccination nation,” further burnishing the reputation of its doctors, but also of its leadership in medical technology, with other countries inquiring as to how Israel rolled out its vaccines. At the same time, the often-justified frustration at the pandemic response led some people around the world into conspiratorial thinking and brought about a wave of antisemitism that Jewish communities have sought to counter. The EU, the US and others have since rolled out plans to fight hatred of Jews.

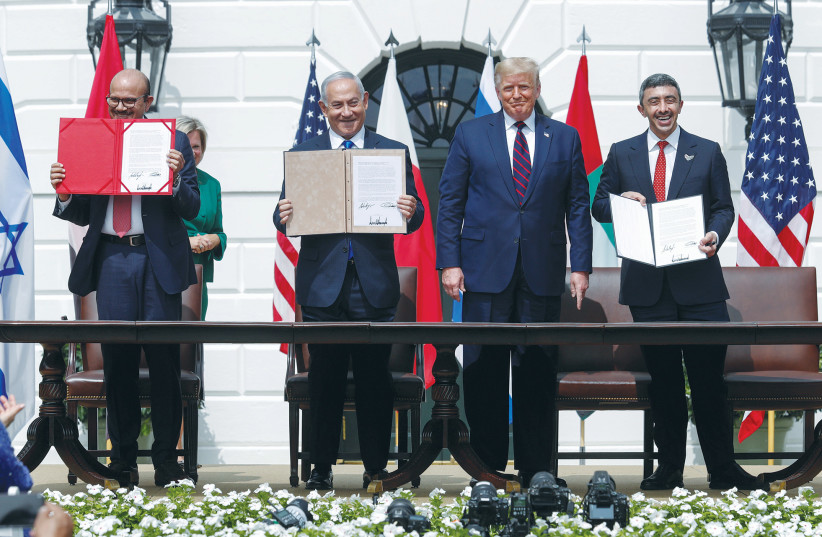

Then, amid the dark days of the pandemic and its lockdowns, came what has been the best diplomatic news of the past four years – and, arguably, of the past three decades: The Abraham Accords.

Different approaches to world issues can make all the difference

Biden also has a very different approach to Iran than the Trump administration’s “maximum pressure” sanctions. His pursuit of a return to the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action was a matter of great concern to the Bennett-Lapid government, which they addressed quite deftly. Bennett and Lapid started with constructive criticism in closed rooms, building trust in Washington, until the indirect US-Iran negotiations reached a point that Jerusalem found intolerable, and then they, together with then-defense minister Benny Gantz, sounded the alarm loud and clear and in public.

The Ukraine war probably had more to do with killing a return to the nuclear deal than Israel did, but the “change government” pressure led the US to give up less than it was going to when talks were still ongoing. By the time Netanyahu returned to office, the JCPOA seemed to be off the table, but in recent months, Washington and Tehran seem to have entered what Netanyahu has called a “mini-agreement,” for Iran to stop enriching uranium in exchange for some sanctions relief from the US – which won’t call it that, but also won’t admit to the deal or report its details to Congress.

The Ukraine War is another massive international event that reverberates in the Middle East. When Russia invaded Ukraine, Bennett hoped he could keep quiet about it, because the large Russian military presence in Syria required coordination between Moscow and Jerusalem in order for Israel to be able to continue to attack Iranian targets near its northern border. In addition, Israel saw and still sees the large Jewish community in Russia as vulnerable to being targeted by Putin’s regime.

However, much of the West took on Ukraine as an important cause and there was pressure on Israel to take a greater stand. Lapid condemned the invasion immediately after it happened and Israel voted with Ukraine in the UN. Bennett, having recently met with Putin, made some aborted attempts at negotiating an end to the war. Meanwhile, Israel sent large quantities of humanitarian aid to Ukraine, including a field hospital and missile warning systems.

When it came to light that Iran was providing Russia with drones, Israel tried to convince the world to be tougher on Iran on the nuclear front. Ukraine tried to use it to convince Israel that they are on the same side. Neither argument seems to have worked particularly well.

A year and a half into the Ukraine war, Israel still says it is on Ukraine’s side and opposes the war, but it has not done much more than it did in the weeks after Russia invaded.

Nearly four years after I started covering diplomacy, the world is a different place. War has returned to the European continent – but Israel has peace with five Arab states, instead of two. The US has returned to its more expected stance on Israel over recent decades than where it was in 2019 – and we’ll find out next November whether it will flip back again.