Researchers in the US and Europe are studying uranium cubes using new methods to determine whether or not they were developed by the Nazis.

During World War II, Nazi Germany and the US were racing to create nuclear weapons. The Nazis had multiple teams working on the project — Werner Heisenberg's group in Berlin and Kurt Diebner's in Gottow. The scientists created cubes of uranium that they hoped would unleash a self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction, but their methods did not work.

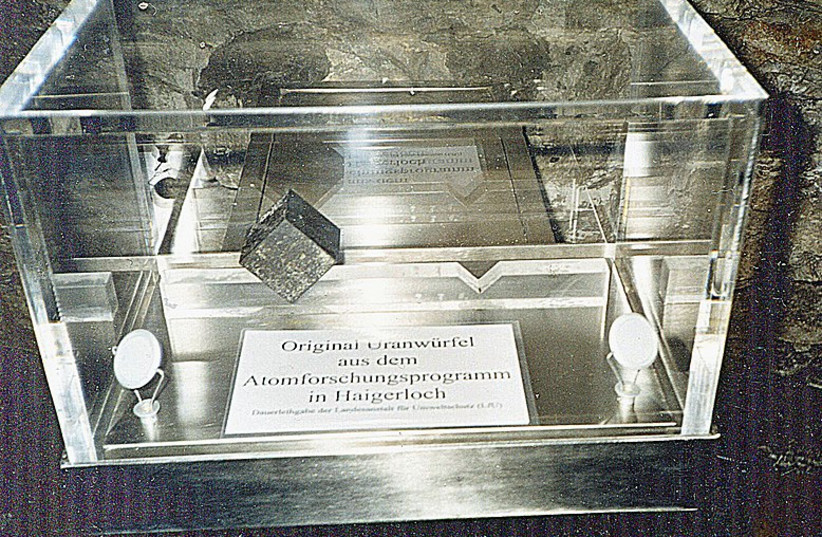

American and British forces disrupted the project before the Nazis could succeed, and they confiscated the cubes, over 600 of which were shipped to the US. Some of them went toward the American nuclear weapon effort and some belong to collectors and the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL), but hundreds were lost track of, and their whereabouts are unknown.

PNNL uses its cube to train international border guards and nuclear forensic scientists to detect nuclear material. They labeled their cube as a Heisenberg cube, but the classification is not certain. "We didn't have any actual measurements to back up that claim," said Brittany Robertson, a doctoral student who works at the laboratory. In order to properly establish the origin of the cube, Robertson employed radiochronometry, a technique used to determine the age of the material based on the radioactive isotope content.

When the cubes were created, they contained pure uranium metal, but with time, radioactive decay separated the uranium into thorium and protactinium. Robertson's research is the adaptation of the radiochronometry technique so that it could be used to better separate the elements and quantify them. The concentration of the elements can tell us how long ago they were made, and Robertson is also refining the method so that it could reveal where the uranium was originally mined.

Another factor that could reveal answers about the cubes is their coating. The PNNL team tested the coating on a cube at the University of Maryland and found that it was coated in styrene. This may have indicated that the cube was not from the Heisenberg group because they used a cyanide-based coating, but the team learned that the Diebner group sent the Heisenberg group some of their styrene-coated cubes.

"We're curious if this particular cube was one of the ones associated with both research programs," said Jon Schwantes, the project's lead investigator. "this is also an opportunity for us to test our science before we apply it in an actual nuclear forensic investigation."

While the researchers are intrigued by their research, they do not forget that these cubes come from a horrific time in history. "I'm glad the Nazi program wasn't as advanced as they wanted it to be by the end of the war," said Robertson. "Because otherwise, the world would be a very different place."

The researchers will present their findings at a meeting of the American Chemical Society.