At 72 days, the Israel-Hamas war is already one of the longest the country has ever experienced.

Founding prime minister David Ben-Gurion realized that Israel was not built for long-term wars, and developed a security concept based on short wars and bringing the battle to the enemy.

Such was the case in the 1956 100-hour Sinai Campaign, during which Israel lost 231 soldiers. So, too, was the case in the Six-Day War, where Israel lost 796 defenders.

This war has far outlasted the Yom Kippur War (19 days), the Second Lebanon War (34 days), and Operation Protective Edge (50 days). Only the 1948-1949 War of Independence, the 1967-1970 War of Attrition, and the 1982-1985 First Lebanon War went on longer.

Ben-Gurion knew that a country of Israel’s size, with the army heavily dependent on reserves and with its sensitivity to casualties, would have difficulty withstanding long, protracted wars. The steady drumbeat of bad news would wear down the population, and the economy could not weather months on end of productive civilians in the reserves.

Israel’s founding security concept was based on the imperative to take the battle to the enemy and win quickly.

That worked when fighting against countries with regular standing armies. But a war with an entrenched terrorist organization is a different matter. For more than a week, the IDF has been saying that, within a few days, it would have control of northern Gaza, yet that complete control – proves elusive day after day.

Not because the IDF is ineffective, but because this type of guerrilla war, in this type of urban terrain, against terrorists hiding in buildings and popping out of the ground, takes time.

The country’s political and military leadership, with all their faults at the outbreak of the war, did well in warning the country at the beginning that this would be a long war. And even if intellectually the country could grasp that, emotionally it wanted to believe otherwise – yearning for a lightning victory like in 1967 or an Entebbe-style raid to free the hostages.

Yet none of that has transpired, and the war grinds on and on.

And as it does grind on and on, there are inevitably highs and lows. On Friday, with the accidental shooting to death of three hostages fleeing Hamas captivity, Israel reached one of the low points of this war so far.

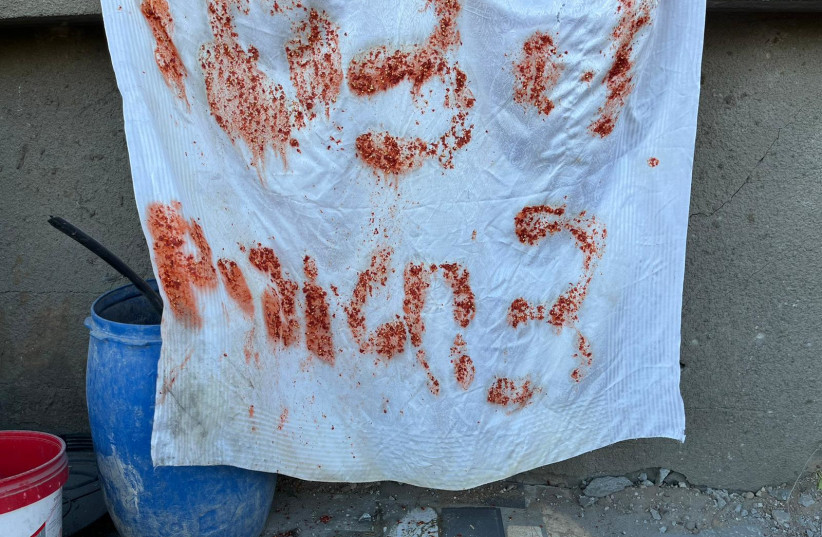

The tragedy and pain in that incident are indescribable. After 70 days in captivity, three hostages, bare-chested and waving a white flag, at one point one of them shouting “save me” in Hebrew, were not killed by Hamas terrorists but by IDF soldiers risking their own lives to find them and bring them to safety.

If, as the cliché goes, war is hell, then this is one of its deeper levels.

It is also the type of incident that can demoralize the nation and the army, the type of incident – if left unchecked – that could start to sway public opinion against continuing the fighting.

It is the type of incident that Hamas leader Yihya Sinwar dreams of: one that triggers mutual recriminations inside Israel and leads to calls to stop the fighting and come to any deal to release the hostages, because “look what happens when the fighting goes on.”

The longer the war goes on, the more types of tragic incidents like this will inevitably occur. Some 20% of the more than 110 IDF fatalities since the ground invasion began on October 27 have been a result of “friendly fire” or accidents, many of them the result of not abiding by standing operating procedures.

Friday’s incident was another example: the three hostages would not have been shot had the soldiers followed standard open-fire procedure. But amid the dangers of a brutal war where around every corner lurks a potential trap, they didn’t follow those procedures.

The circumstances need to be examined, the regulations need to be reinforced, and the soldiers need to be briefed before going into battle of the possibility of fleeing hostages, but this need not, must not, nor has not turned public opinion against the war.

Israel needs to take a deep breath, and as painful as it is – and every day the pain grows more and more as names are added to the list of the fallen – must continue to pursue the aims of toppling Hamas, rescuing the hostages, and deterring other regional enemies.

One of the reasons Israel finds itself in this current war is because, in previous rounds of fighting in Gaza, it was not willing – as many in the Gaza border communities had pleaded – to “finish the job” and eradicate Hamas.

One of the reasons Prime Minister Netanyahu was not willing to finish the job was concern about casualties, and what he viewed – based on the experience of the Yom Kippur War in 1973 and the withdrawal from Lebanon in 2000 – was the public’s inability to handle the casualties he believed it would take to bring Hamas to heel.

Israel had a chance to topple Hamas in 2008-2009 during Operation Cast Lead, but stopped before the job was completed. The same was true of Operation Defensive Shield in 2014.

The leadership at that time, gauging the sentiments of the nation, was reluctant to engage in a prolonged war. They were uncertain about the country’s capacity to endure such a conflict and were concerned that despite the initial enthusiasm, as negative news emerged – something inherent in wartime – the public’s support for the war and willingness to bear its costs would diminish, potentially leading to public opinion turning against the war.

It is also the same thinking that prevented the government from taking military action to prevent the buildup of Hezbollah’s enormous arsenal following the Second Lebanon War in 2006.

The traumatic day that changed everything

Then October 7 hit and the equation changed.

Suddenly, because of the pure evil and savagery of the attacks, the public appeared to feel that Israel needed to do what it takes, as long as it takes, to remove this threat. There was a realization that no life-aspiring nation could live with terrorist organizations hell-bent on destroying it operating within a stone’s throw of communities it was hell-bent on destroying.

That Friday’s incident did not lead to more than just a few scattered calls to reassess the military’s goals and tactics – but not to a wave of protest to end the fighting – says something about the depth of the trauma of October 7. It also bespeaks of an internalization that security problems do not go away or become more manageable with time. On the contrary, if they are allowed to fester they only become more difficult to deal with.

Israel is dealing with a security problem it could have dealt with years ago but – for the sake of temporary quiet – didn’t want to. Now there is a sense that it must deal with the problem, to such an extent that Friday’s incident – while profoundly tragic and deeply painful – is not leading to any significant calls to reassess the country’s overall war aims in Gaza.