I saw many dads one day.

We had all come to join the army right away.

There was a lawyer dad, and a builder dad,

A traffic cop dad, and a journalist dad.

Dads who work in the office, and dads outside,

Dads who knew how to fix everything they eyed.

There were dads who could style a princess’ hair,

And dads who could tell every joke they’d dare.

Perhaps, even your dad was there.

Everyone arrived as fast as they can,

Some later, and some earlier, who really ran.

We left behind children and family

It wasn’t easy, not everyone says goodbye happily.

But sometimes you just have to go, or at least try,

We’ll miss you later, we said, it’s time to get the bad guy.

This passage was written by Maj. Boaz Payne, a 46-year-old reservist fighter in Battalion 28 of the 55th Paratroopers Brigade. It was also written by Boaz Payne, father of 14-year-old Yehonatan Yehuda; Yael Hallel, who is about to celebrate her bat mitzvah; and seven-year-old Noga Noam. Two completely different people within one man.

Since October 7, hundreds of thousands of reservists have assumed this split personality, crossing into another dimension just a few kilometers away, yet so incredibly far that most people cannot fathom it.

Your reality suddenly becomes separate from that of your kin, your fellow Israelis, to the point where the gap to understanding one another, even your closest friends and family, can seem unbridgeable.

So Payne started drawing. Next to his poetry are his cartoons.

“We don’t know how to tackle a way of communicating with family, communicating with friends; there’s a huge gap. How do I convey that we’re in a place that’s shattered, dirty, glass on the floor; people are packing their excrement in bags. I looked at the drawings and saw them as something we can use as a means of communication. It’s something I like to do, the elaborate and humorous drawings. I use them to talk to my wife and kids,” he says.

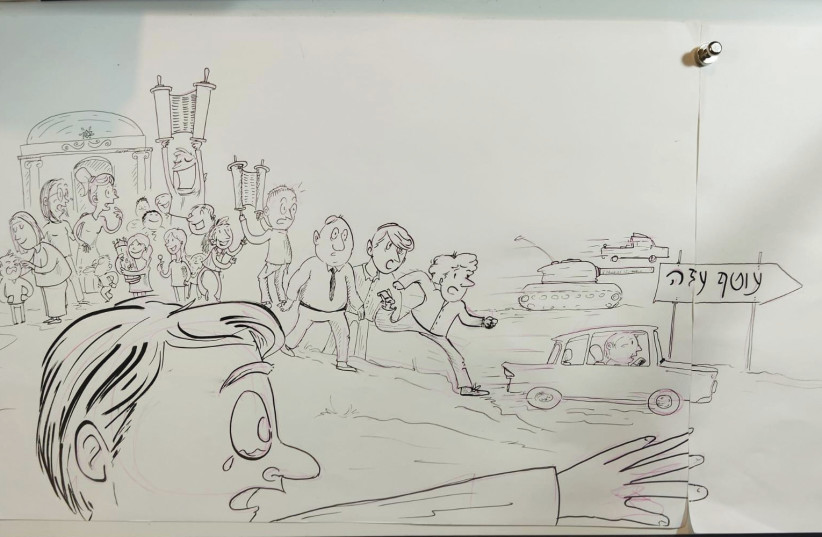

The characters are almost satirical, carrying, trudging along, taking photographs, growing mustaches, making mud coffee, and fighting. Their long, pointy noses bear a striking resemblance to those of Nigel Thornberry [a character on the animated American TV show The Wild Thornberrys], vibrant and full of life, in contrast to the desolate environment.

Payne says, “We think about war – it’s brutal and chaotic and alarming, but in the end, just like when you’re home and you’re casually living your life; and once you get used to it, it’s the same thing in war – you do what you do. That’s the feeling I’m trying to convey. I’m a father, I’m a spouse, I’m a manager, I’m a consultant, and yeah, I’m also a fighter. It’s just difficult to explain because it lacks a parallel to reality.

“This is our life at the moment. It becomes normal.”

In another drawing, a D9 Caterpillar bulldozer – one of the more striking symbols of the fighting in Gaza – is surrounded and captained by people making phone calls.

“The D9 is supposed to be shocking – it’s picking everything up with it, for protection and shielding during battle, but people were allowed to bring phones into Gaza, so I wanted to show the contrast of this huge metal monster, versus the driver just calling his family on the phone,” he says.

“You come home; you’ll sit with the wife and kids and they’ll go, ‘How was it? Tell me something about Khan Yunis, something about Gaza,’ and you’d say, ‘It was okay, I was tired, it was hard.’ We have limited words, but once you start painting an image, it becomes clearer,” Payne explains. “I can only tell the stories that I can tell.”

ANOTHER OF Payne’s images shows reservists making their way to the Gaza Strip on October 7, leaving behind whomever they had at home, their families, their wives – and are about to enter a different reality.

“People are starting to realize that nothing will remain the same. We have people who are secular and Orthodox; Left and Right; Druze and Jews; from Tel Aviv and from the settlements. We’re the people of Israel. From the pain, the greater essence of Israel has emerged. We need to see that, too.”

There’s also a constant presence of animals in the drawings.

Payne tells the Magazine that there were multiple encounters with animals: “As we were raiding Hamas HQ, someone said ‘Look out! There’s a dog in a cupboard.’ I opened the cupboard, and there was a really cute dog with big eyes, completely terrified. Ten minutes before that, we saw a chicken running under a tent. We found four abandoned puppies, and my friend Baruchy gave them up for adoption.

“This contradiction between a place of death and all this life. We have to do what we do, but we don’t have to be vicious.

“Sometimes we have to do things that aren’t pleasant. In the pursuit of justice, you have to destroy, to kill. Our ability to remain focused on the goal and on the mission and still preserve who we are is a great strength.”

A source of healing and comfort amid the Israel-Hamas War

PAYNE’S PROJECT is growing. He hopes to turn it into a source of comfort, help, and maybe even create a book.

“I have until the end of the reserves to pick up more stories,” he says.

“I love my day job. I really enjoy it, but this is the first time I’m more than enthusiastic about creating something. I can do my small part. I hope that in the future, my vision can be published. But if not – I did my part.”

In a post-October 7 world, as the fog clears, the number of people who will suffer from PTSD will be unprecedented. Lives and families will be torn apart. Understanding how to manage and express one’s experiences and feelings is a big part of the healing process. Payne’s initiative can certainly be a part of that.

“We have a phrase in the army when things get tough. We look at each other, and we bless God that we’ve had the chance to be a part of the greater Israel story,” he says.

The last passage, for a page of the book yet unfinished:

So if your father’s back from the war,

Sit down and talk about what he went through.

Sometimes it’s difficult, but I hope this book can help.

And for now, I’m sending big big hugs to you both.