For a people with a long history, we have a short political memory.

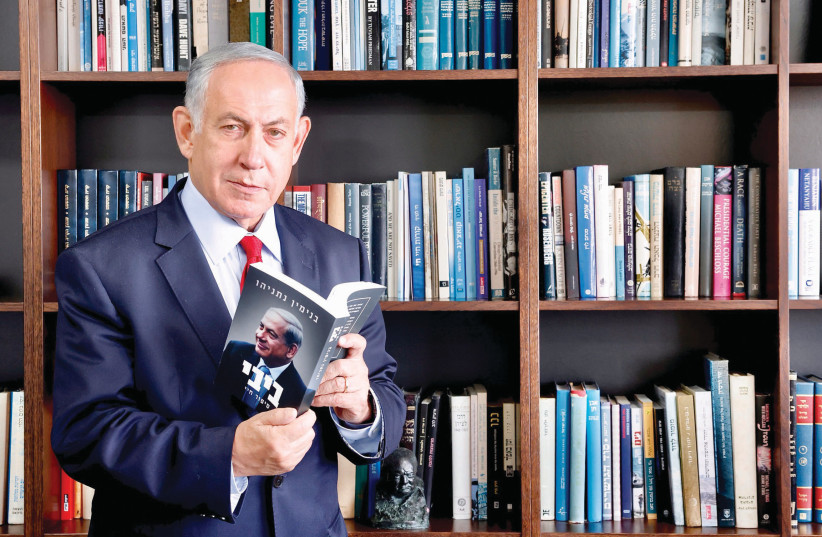

Judging by the apoplectic reaction of some to plans to move the functions of one government ministry to the authority of another, one might have thought that presumptive prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu – in either agreeing to or initiating these changes – is brazenly going where no Israeli prime minister has ever gone before.

Wrong.

Similarly, judging by the hand-wringing accompanying Religious Zionist Party head Bezalel Smotrich’s interest in getting control of the Civil Administration in Judea and Samaria primarily to benefit those he views as his constituents – Jews living beyond the Green Line – one might think that a minister using his power to help those who vote for him has never been done in Israel before.

Wrong again.

Both phenomena have long been a part of Israeli politics. What is different this time is the authority of the ministries being diluted, as well as the identity of the constituents who benefit from what is essentially pork barrel politics – funding government programs or projects for a specific constituency whose costs are borne by everyone.

None of this is meant to imply that these two phenomena lead to good or fair governance. They don’t. But these are not new and nefarious developments that have suddenly just popped up on the political scene.

When Mapai and then the Labor Alignment were the country’s dominant political forces from 1948 to 1977, the kibbutz movement benefited enormously because of the political patrons it had inside the government. The same thing happened to the settlement movement after Menachem Begin took over in 1977, until Yitzhak Rabin won the 1992 elections and changed the nation’s priorities.

Haredi parties and Likud

The haredi political parties discovered, upon joining the Likud government in 1977, the benefits of sitting around the government table where budgets are allocated. Funds for haredi institutions rise when the haredi parties are in the government, and fall – as they did over the last year and a half – when they are not, which is why Shas and United Torah Judaism desperately want to get into the next government.

United Arab List (Ra’am) leader Mansour Abbas also understands how this works and made no secret that he wanted to join the outgoing government to get more funds for his sector. Abbas’s historic gambit played off – at least on paper – as the Arab sector was allocated some NIS 50 billion under the last budget (though the vast majority of that was not delivered by the time the government fell).

Unfortunately, Israel’s system promotes a “to the victor go the spoils” political culture, which Smotrich, by wanting to have control of the Civil Administration in the West Bank, is trying to capitalize on.

Some argue that what he is trying to do by gaining control of the Civil Administration is de facto annexation. Although that may fit into his ideology, the actual reason is likely less dramatic: to benefit his voters.

Smotrich’s RZP is strong in the settlements. The way things are set up now, if a settlement head wants to put up a new preschool, or expand a road, or if someone living in a settlement wants to add a new room to his apartment, he needs approval from the IDF, which administers the territories. Under the new situation, the process would be streamlined and made more manageable; in other words, it is a form of “pork” Smotrich is throwing to his natural constituents.

Pork barrel politics is not an Israeli phenomenon. It exists everywhere. But there is a difference. In the US, for instance, the constituents in the state of Nevada will always have representation in Washington, since they will always have two senators and several congressmen who will look out for their interests and direct federal funds toward the state.

However, if a particular sector in Israel is not around the cabinet table when the budget is being divvied up, fighting for its share, it may not get its fair share. Having representatives in the Knesset is not enough; ministers around the table are what makes the difference. When sectors that have been left outside the table then get a chance to sit around it again – which is what is happening now – there is an unhealthy inclination to gorge, or take more than a fair share. Why? Because they can.

ANOTHER RECURRING phenomenon in Israeli politics is the creation of new ministries out of thin air, or slicing authority away from one ministry and giving it – for reasons of political expediency – to another. This, too, is nothing new. One need not look too far back for examples. In July 2021, for instance, mercurial Yisrael Beytenu MK Eli Avidar was appointed a minister in the Prime Minister’s Office for strategic affairs to ensure that he would vote for the budget.

In addition, to solve various political problems and keep various people happy, the outgoing government in July 2021 decided to transfer the Labor Division of the Labor, Social Affairs and Social Services Ministry to the Economy Ministry. It then took some of the responsibilities from the latter ministry and transferred them to the Science and Technology Ministry, renaming it the Innovation, Science and Technology Ministry – all in order to make that ministry politically more attractive.

None of that was new. For years ministries have opened and closed, with responsibilities shifted around. Just ask anyone in the Foreign Ministry, where that ministry’s authorities have been severely diluted over the years, as the responsibilities for Diaspora communities, public diplomacy, and the battle against the Boycott, Sanctions and Divestment movement have – at various times – been moved to other ministries.

While there is always a bit of screaming and shouting when this takes place, the issue has caused an unusual amount of consternation this time because of the personalities and the ministries involved.

Had the branch that oversees the external content in the education system been taken from the Education Ministry and given to someone other than Noam’s Avi Maoz, a man who is stridently opposed to homosexuality and has said in the past that a woman’s place is in the home, it is unlikely to have caused the uproar that it has over the last two weeks.

In 2020 the Education Ministry lost control of higher and supplemental education to a newly formed ministry of that name that Ze’ev Elkin headed. Even though the Education Ministry lost more authority to Elkin than it is losing now to Maoz, there was less of a public upheaval. That, of course, has to do with Maoz.

There is also much more protest this time than in the past at transferring authority and responsibilities from one ministry to the next. This has a large part to do with the ministry in question that risks losing some authority: the Defense Ministry.

Under the emerging coalition agreements, Smotrich’s RZP will have a minister in the Defense Ministry who will be in charge of “Jewish settlements and open lands.” In addition, authority for the Border Police in Judea and Samaria is slated to be taken from the Defense Ministry and given to the new National Security Ministry that Itamar Ben-Gvir will head.

Defense Minister Benny Gantz said this week that if this is done, presumptive defense minister Yoav Gallant will be a “second-class defense minister” with limited power.

The satirical program Eretz Nehederet illustrated this situation in a sketch Wednesday night in which a character portraying Netanyahu gives an actor meant to be Gallant a large duffle bag that is the defense portfolio and symbolizes the enormous authority that this ministry currently has.

When informed that responsibility for the Civil Administration in Judea and Samaria is to be taken away, the large duffle bag – the defense portfolio – is replaced by a backpack. This backpack then shrinks to a pouch – the “defense pouch” rather than defense portfolio – when the authority over the Border Police is given to Ben-Gvir.

When Gantz says that at least he will still have responsibility for dealing with Iran, Netanyahu says that this issue is his “baby,” and Gantz is given a small wallet – all that is left of the once massive defense portfolio.

This is also not the first time that authority under the Defense Ministry has been parceled out. In 2011 the Home Front Ministry was created and, because of political expediency, given to Matan Vilna’i, who – along with Ehud Barak and three others – split from the Labor Party and stayed in Netanyahu’s government. Much of the authority of this new ministry was taken from the Defense Ministry.

There was debate about the issue then as well, but much tamer and less apocalyptic than now.

Giora Eiland, who knows a few things about how large organizations work, since he served both as head of the IDF’s planning and its operations directorates, and also as director of the National Security Council, wrote this week that humanity has progressed largely because people have learned to cooperate with each other, and that they do that through the establishment of efficient organizations.

“An efficient organization is characterized by four things,” he wrote. “It has a clear hierarchy; authority is delegated throughout the pyramid; processes are improved based on experience, and all this is achieved at minimal cost.”

The new arrangement under the coalition agreements will harm the efficiency of most government organizations, he wrote. For example, he said, moving authority for supplemental education to Maoz’s hands will make decisions much more cumbersome.

Because of the public outrage over Maoz’s appointment as a deputy minister in the Prime Minister’s Office with authority over supplemental education, Netanyahu clarified this week that all of Maoz’s decisions would need his approval. This is simply inefficient, Eiland wrote.

From a situation where the head of the external education department is authorized to make decisions on his own, now all decisions will have to go up the ladder to the prime minister. The problem with that, Eiland said, is that the prime minister “is the busiest person [in the government], and the guiding principle needs to be that his direct responsibilities need to decreased, not increased.”

Furthermore, regarding moving responsibilities from one ministry to another, Eiland wrote: “Every change, even desired change, is accompanied by a hidden cost called ‘the cost of change.’ The very act of moving departments and authorities, the very act of splitting up and putting them together, creates heavy costs arising from the need to make adjustments to computer systems, laws, work agreements, regulations and how work is done. Instead of the government ministries dealing with their main purposes – providing solutions to the public – they will deal with themselves.”

The net result, Eiland concluded, is not better but, rather, worse governance.

Unfortunately, though, the political dynamics leading to this state of affairs are neither unique to the government in formation nor to the ongoing coalition negotiations.