This past week, Ashkenazi synagogue services were marked by Yizkor, the memorial prayer for loved ones recited on the three major festivals and Yom Kippur. In most synagogues, attendees who have never had to sit shiva (i.e., have never lost a parent, sibling, child or spouse) walked out before the memorial prayers are recited.

This is very unique. I can’t think of any other time in which we encourage some people to leave the synagogue in the middle of a service!

As Zvi Ron has documented, the first record of this custom appears in a work published in 1815, which notes that it seems to be a long-standing practice. Some were concerned that walking out was a superstitious practice. Rabbi Baruch Brandeis asserted that while he couldn’t find any recorded rationale for the practice, he suspected that there was a concern that everyone in the synagogue would feel compelled to say the prayer. Fearing that people whose parents were alive would errantly say these words, it was suggested they leave the room.

Why do some Jews leave the synagogue during Yizkor?

Other scholars argued that it would be inappropriate for synagogues to have some people praying while others remain silent. If you can’t pray with the congregation, then step outside. A couple of scholars speculated that children or others not reciting the prayer would talk or otherwise distract those reciting Yizkor. In a different vein, a few contended that it is generally inappropriate to participate in a mourning ritual on the festival. Only for those who have someone to remember is this commemorative ritual meaningful and therefore uplifting and appropriate for a holiday.

Another explanation was that the “evil eye” (ayin hara) would be invoked against those who remained present in a room full of orphans. Although many scholars like Maimonides downplayed the existence of an evil eye, many Jewish scholars raised this as a real concern in many circumstances. A similar explanation noted that it is common for children to be named after the deceased forefathers whose names are being recited in the Yizkor prayers. Accordingly, it is considered “opening one’s mouth to the Satan” to mention these deceased names in the presence of the similarly named living descendant.

The myth that Judaism looks down on talking about death

This explanation became popularized and has helped build up a myth that Judaism looks askance at talking openly about mortality. In some ways, this ritual is paralleled by the widespread (albeit disputed) custom of chanting in an undertone the Torah portions that rebuke the Jewish people and prophesize times of travail. The impression, as it were, is that talking about tragedy might bring it upon us.

Yet such a perspective is overly simplistic. For starters, some decisors ruled that if a person can’t physically walk out of a Yizkor service (say, because it is muddy outside), then there is no concern to remain in the sanctuary. If we were so afraid of the evil eye, this would be intolerable.

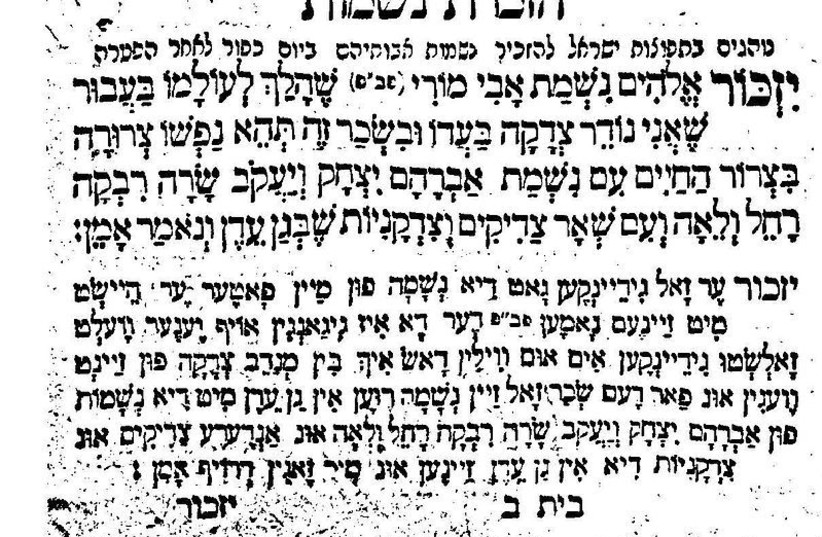

Yet more fundamentally, the magnified cultural prominence of Yizkor and this curious practice overshadows the fact that our first daily prayers are references to death and mortality. The first prayer we recite upon awakening, Modeh Ani, gives thanks for our renewed life. Soon after, the prayer known as Elokai Neshama thanks God for restoring our soul while acknowledging that God will eventually take it from us. Our daily prayers, as the late teacher Dodi Tobin emphasized in a moving lecture before her death, call upon us to confront our mortality. Indeed, the Talmudic sage Rabbi Eliezer beseeched people to repent today lest they die tomorrow.

Beyond raising spiritual awareness of one’s mortality, the Sages permitted and sometimes encouraged practical planning for one’s death. Recognizing that death may come suddenly, some Sages deemed it appropriate to buy one’s own death shrouds “just in case” they become needed on short notice. The sage She’ila bar Avina, in fact, asked his wife to prepare his shrouds because he feared he would die for a transgression against another sage. When his time came shortly after, his family was prepared.

“Praiseworthy is the person who purchases their death shrouds when they are alive and healthy. For they follow the great adage ‘If I am not for myself, who will be for me?’”

Rabbi Chaim Palaggi

Following this sentiment, Rabbi Chaim Palaggi, the 19th-century Ottoman Empire scholar, asserted, “Praiseworthy is the person who purchases their death shrouds when they are alive and healthy. For they follow the great adage ‘If I am not for myself, who will be for me?’” He further noted that people who confront their mortality will take life more seriously and avoid sin.

In a similar spirit, the medieval scholar Nahmanides argued that healthy people should dig their own graves! Others weren’t as enthusiastic about such practices. Particular concern was raised that digging graves for the terminally ill would cause despondency and emotional anguish, thereby hastening their death. Yet advanced planning does not have such concerns. In modern times, this entails purchasing burial plots in advance so that funeral arrangements won’t be done in haste. Indeed, Rabbi Moshe Sternbuch asserts that such wise planning is a segula (merit) toward a long life! Other scholars, like Rabbi Yisrael Kagan, encouraged people to draw a financial will by the time they are 50. He, too, cited the famous adage “If I am not myself, who will be for me?” If you want your wishes fulfilled, you need to be proactive and willing to speak about your mortality.

In this spirit, the Ematai organization is launching several initiatives to help Jews navigate the dilemmas posed by aging and end-of-life care because Judaism isn’t afraid of confronting mortality. And if not now, when? ■

The writer is executive director of Ematai and author of A Guide to the Complex: Contemporary Halakhic Debates. www.ematai.org