Irwin C. Gerson – my “Uncle Irv” who succeeded in America as “Win” – died last Shabbat. He was 93. Epitomizing American Jewry’s boundary-breaking “Generation Making It,” his lessons about America, Jewish pride, and Zionism, and about living our dreams, will long outlive him.

Born in March 1930 during the Great Depression, Irwin’s mission was clear. His parents, my grandparents, made it to America from Eastern Europe – that was their miracle. He would make it in America – that would be his miracle – and ours.

Growing up in the South Bronx wasn’t easy. His pharmacist father struggled through the Great Depression, and he sometimes struggled on the streets. One St. Patrick’s Day, Irish and Italian toughs turned my mother’s new blue coat white, by pounding her with socks filled with talcum powder that were usually aimed at her older brother’s head.

He distinguished, of course, between “those” Jew-haters and “the” non-Jews. As an adult, he worked easily with all kinds of people – even scandalizing my grandfather by visiting Germany on business. Unapologetic, he leaned into his Jewish pride, even when hosted on baronial estates whose owners were not sufficiently embarrassed by their fathers’ crimes. He was wise enough – and secure enough – to know how low the Germans had gone, while appreciating how far he and our people had come.

Combining Mel Brooks's wit and Moshe Dayan's grit, Irwin and his peers turned potential traumas into memorable punch lines. If someone had poured shellfish outside their Jewish fraternity (as happened recently at University of California, Berkeley), they wouldn’t have allowed themselves to feel victimized. Members of his generation were programmed to pull off some clever revenge prank rather than file formal complaints. Rejecting today’s snowflakes, he scoffed: “You call it a hate crime... we called it life.”

Advocating for Israel before the nation's birth

In his bar mitzvah speech in 1943, delivered in America-the-safe two weeks after the Nazis liquidated Krakow’s ghetto, young Irwin insisted: “the homeless Jewish wanderers must be given the right to live the life of a free nation in the Land of Israel.”

That historical consciousness explains the gleam in Uncle Irv’s eye whenever he talked about how well Jews had done in America. And that Zionist consciousness explains his staunch support for Israel – he saw how Jews suffered without a Jewish state. He knew the miracle he lived – and we still live.

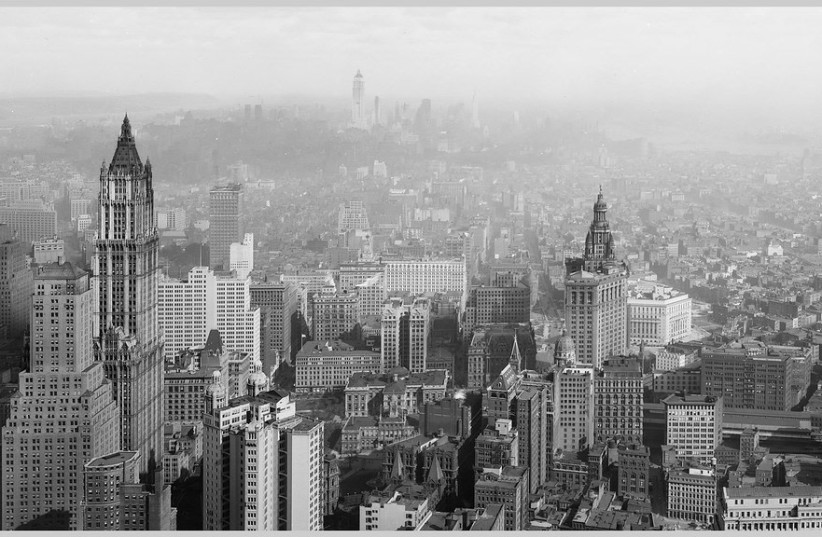

After serving in the army, Win entered the family business, with a profitable twist. He became a pharmaceutical advertising executive from the Mad Men television show’s era. He summarized his fast-paced career by saying that in New York, “the one constant is change.”

Win Gerson became our family’s class-climbing champion. When he moved to the fancy suburb of Scarsdale or attended Metropolitan Museum of Art galas, we all felt like we had arrived. With apologies to Frank Sinatra, “if he could make it there,” we believed we could “make it anywhere,” too.

Even as kids, we noticed how hard Win worked, especially because the professional often blurred with the personal. My mother marveled how his wife, Aunt Lenore, whipped up last-minute dinners when Uncle Irv brought “work friends” home. And although his hobnobbing and globe-trotting seemed glamorous, it must have been draining, too, extending the workday and their “on” time indefinitely.

While climbing up, Uncle Irv joined many American Jews in dropping traditional Judaism, especially the ritual-oriented “noes.” So my super-successful uncle was also the “Reform” uncle, fleeing my grandfather’s intense, rigorous, proud, hyper-literate, Israel-centered, Jewish world. This gap between the Judaism we lived and the Judaism he chose triggered the “Seder Wars,” an annual shouting match about just when (or if!) our interminable Passover Seder would ever end.

Eventually, we grew past these tensions, as we entered his world through the Ivy League, and it became clear that he really hadn’t rejected his father’s world. In his circles – and upon retiring to the other Promised Land, Florida – his inherited Jewish literacy made him the Jew-in-Chief. He ran the Seders. He defended Israel. He read Jewish-themed books voraciously and supported Jewish causes generously, from the local Federation to the Yiddish Book Center to the Israel Museum.

Irwin Gerson’s magical life proves that even today, with all its challenges, America remains the beacon of light for millions – that’s why so many successor-immigrants to my grandparents keep coming. He started with no privilege, no connections, no role models. He only had those two essential seeds for success – smarts and a work ethic.

Uncle Irv lived the full American dream – succeeding professionally and personally. His 70-year marriage to Lenore was a beautiful partnership that produced two children, three grandchildren, and three great-grandchildren... and counting. Through his family values, his love and support for all of us, his charitable works, and his zest for life, he set ethical standards as towering as his professional standards.

His trailblazing peers in “Generation Making It” raised us “Generation Hope,” the lucky winners of the historical lottery, born into freedom and prosperity. Yet, somehow, today’s next generation seems to be auditioning to become “Generation Despair.”

This Rosh Hashanah, let’s remember how far we have come since 1930. Let’s honor the memory of Irwin “Win” Gerson, aka Kalman Yisroel ben Aryeh Leib v’Zahava, by telling his story of personal and collective redemption – or your own family’s passage from the misery of yesterday to the joys of today – taking his and our leap of hope that tomorrow will be even better.

The writer is an American presidential historian and, most recently, the editor of the three-volume set, Theodor Herzl: Zionist Writings, the inaugural publication of The Library of the Jewish People.