Our world is moving ahead at warp speed, for better or worse. The pressure to innovate is tremendous because if everybody else moves fast, we will be left behind unless we keep pace with the competition. So, we come up with bold, fresh and innovative ideas, which we hope will propel our business forward – and then we may make a misstep, rushing too soon to seek patent protection. A proper perspective of the need to reconcile haste with purpose is essential.

Entrepreneurs at all levels sometimes operate under the misconception that to safeguard their intellectual property (IP), it is sufficient to state a desired goal, describe it in general terms and file a patent application to beat the competition at obtaining a so-called “priority date.” Unfortunately, that is typically far from sufficient and, in many cases, is a self-defeating practice. Too often, patent applications submitted prematurely based on insufficient practical knowledge come back to haunt their owners.

There is a sharp difference between dreamers and inventors, which may be hard to appreciate because seeing the dividing line between the two requires a combination of legal and technical expertise. Once this difference is recognized, entrepreneurs can act better in tune with their needs. Thus, it is worthwhile taking a good look at the gap between the two.

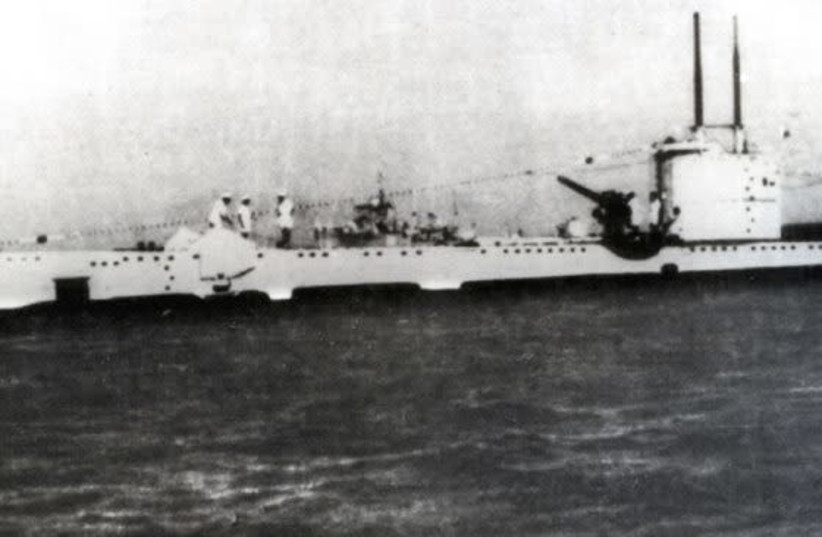

A simple example that illustrates the point is the invention of the submarine (which was not made by Jules Verne, contrary to common belief). In 1578, the British mathematician William Bourne described the idea of a submarine in a book. However, his submarine would not have been eligible for a patent because he only described a general idea. Bourne was a dreamer.

42 years later, Dutch inventor Cornelis Drebbel built the first navigable submarine, which dove under the Thames River in 1620. Drebbel was an inventor. He possessed all the technical information needed to turn Bourne’s dream into an actual working device.

Unfortunately, life nowadays is more complex and full of pitfalls than it was in the 1600s. The modern dreamer is not clueless like Bourne was; he has practical knowledge and can include actual technical details in the “description of his dream” (which often takes the form of a provisional or other patent application). However, it so happens that what we often see in patent applications of this kind can be described as both “too little and too much.”

“Too little” means that the technical details described in the patent application do not satisfy the basic requirement of the sufficient description needed for a valid patent to be granted. “Too much” means that the limited description contained in the patent application is sufficient to render obvious (and hence, unpatentable) any new, complete patent application that the dreamer-turned-inventor will file in the future.

The reader will say, at this point, that this appears to be a lose-lose situation: If I file my patent application too soon, it won’t be any good, and if I wait, someone else will beat me to it, right? Wrong!

Drafting a patent application is not simply putting together pages of information and hoping for the best. It is an endeavor that requires detailed consideration of many factors, which will dictate what should go into a patent application filed at a given time and, more importantly, what should not go into it. It should further be considered a building block of the company’s IP assets, which may need refinement as time passes. Readers who practice gardening know that certain fertilizers required by a mature plant would kill a tender sprout, just like words written carelessly may kill your hope of strong IP protection.

The pressure to move ahead quickly to protect our IP should not make us forget that “fast” and “good” are not synonyms. Still, there is no need to slow down if we treat our IP as considerately as it deserves. The faster we need to work, the more critical it is to consider all the implications of the dreams we are about to narrate in our patent application and leave out those dreams that, no matter how beautiful, will not further our commercial goals. That will give those dreams a better chance to come true.

The writer is the president of The Luzzatto Group and one of the best-known Israeli patent attorneys.

Dr. Kfir Luzzatto will present at The Jerusalem Post Annual Conference. To watch live on October 12 (or see the recording anytime thereafter), click here.