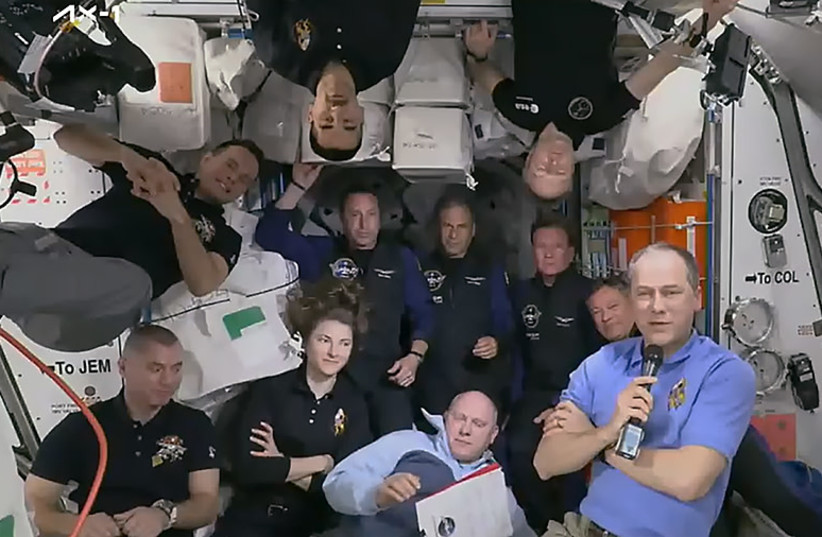

Researchers conducting the first Israeli biomedical research on the International Space Station believe that Eytan Stibbe’s vision will not deteriorate during his short space flight.

The last time vital signs and physiological parameters were taken from an Israeli in space was in 2003, from Ilan Ramon, the first Israeli astronaut.

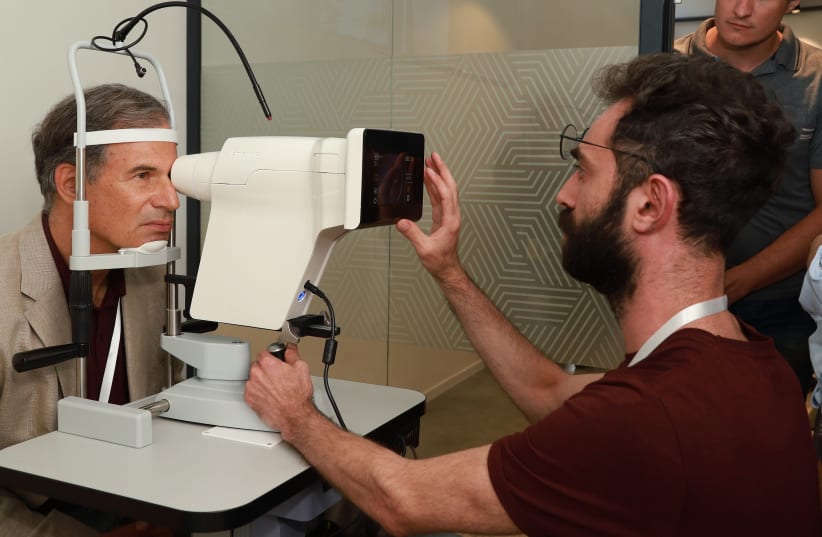

Now, vision tests have been performed from earth several times on Stibbe, the second Israeli astronaut who is due to return to earth on Wednesday, and the last test will be near the end of the mission on the International Space Station. He was launched into space for a private, 10-day mission on Elon Musk’s SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket.

The study was supervised from the Rakia ground control center in Tel Aviv by Prof. Uri Polat, head of the School of Optometry and Visual Sciences; Prof. Yossi Mandel, head of the Science and Ophthalmology Engineering Laboratory at Bar-Ilan University in Ramat Gan; and Dr. Eran Schenker, a space physician and medical director of the Israel Aerospace Medicine Institute.

Prolonged exposure to microgravity conditions during space missions can impair vision. Symptoms reported by astronauts who have been in space include decreased vision, changes in the optic nerve and retina, and a difference in refractive error, which involves problems with focusing light accurately on the retina due to the shape of the eye and/or the cornea.

The digital vision test via a tablet or mobile phone diagnoses visual acuity without a need to go for an eye test. “I have to say that after a year of demanding work and endless meetings with space agencies officers, representatives of SpaceX and Axiom team are in the ground space mission control center connected to the space station and waiting for confirmation that the study has been successfully completed,” said Polat.

“While monitoring the study in the ground control, an astronaut conducts the first Israeli research in the field of vision on the International Space Station,” added Mandel. “It is a dream that has become a reality and a breakthrough for many other medical studies in the future.”

Schenker, who has studied a variety of biological phenomena in space over the past quarter-century, recalls that this is not the first Israeli space mission. “It took more than five years before Israeli researchers were once again dispatched to the space with Israeli technology coordinated by the Israel Aerospace Medicine Institute (IAMI),” he said. “IAMI was able to launch studies on all NASA space shuttles back then. With SpaceX technology and Axiom-1 mission, more than 30 studies have been launched to the space station, and they are being complemented by Eytan Stibbe.”

Schenker added that the mission will surely contribute greatly to understanding the visual functions in zero-gravity conditions and greatly assist in planning long-term space missions to the moon and further, even to Mars.

Neuro-ocular syndrome (SANS) was reported recently as a result of prolonged exposure to weightlessness. Little information is currently available on the subtle, in-flight effects of weightlessness on spatial and temporal visual function during flights of short duration.

The current research is aimed not only at evaluating the effects of weightlessness on visual function, but also how much recovery of the visual functions occur upon return to normal gravity. This study thus signifies a technological and scientific advance in the ocular field in space, all stemming from Israeli innovation.

The study of visual changes and intracranial pressure (ICP) in astronauts on long-duration flights is a relatively recent topic of interest to professionals in the field of space medicine. Although reported signs and symptoms have not appeared to be severe enough to cause blindness, the long-term consequences of chronically elevated intracranial pressure is unknown.

NASA has reported that 15 long-duration male astronauts aged 45 to 55 years of age have experienced confirmed visual and anatomical changes during or after long-duration flights. Stibbe, an Israeli billionaire who paid his way (to the tune of $50 million) to join the mission, is 64 years old.

Optic disc edema, globe flattening, choroidal folds, hyperopic shifts and an increased intracranial pressure have been documented in these astronauts. Some individuals experienced transient changes post-flight while others have reported persistent changes with varying degrees of severity.

Although the exact cause is not known, it is suspected that microgravity-induced cephalad fluid shift (a significantly altered distribution of fluid within the compartments of the head and body) and comparable physiological changes play a significant role in these changes. Other contributing factors may include pockets of increased carbon dioxide and an increase in sodium intake.

CO2 is a natural product of the metabolism, and people typically exhale around 200mL of the gas per minute at rest and over four liters at peak exercise levels. In a closed environment, CO2 levels can quickly rise and be expected to a certain degree in a space station.