A yeast that could be used to prevent invasive candidiasis – a major cause of death in hospitalized and immunocompromised patients – has been identified by researchers at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot.

The study, just published in the Journal of Experimental Medicine, shows that the novel yeast lives harmlessly in the intestines of mice and humans, and – as has so far been shown in lab animals – it can displace the yeast responsible for candidiasis, Candida albicans.

Millions of microbial species live within or on the human body, many of them harmless or even beneficial to human health. Among these are various species of yeast, which belong to the fungus kingdom.

The microscopic yeast Candida albicans, commonly found in the intestines and the body’s inner cavities, is usually benign, but occasionally it may overgrow and cause superficial infections commonly known as thrush. Under certain circumstances, however, the yeast may penetrate the intestinal barrier and infect the blood or internal organs. This dangerous condition, known as invasive candidiasis, is commonly seen in healthcare environments, particularly in immunocompromised patients, with mortality rates of up to 25%.

Candidemia is one of the most common bloodstream infections in the US. Between 2013 and 2017, the average incidence (rate of new infections) was approximately nine per 100,000 people, but this number varies substantially by geographic location and patient population. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that some 25,000 cases of candidemia occur nationwide each year.

Though it is the most common form of invasive candidiasis, candidemia does not represent all forms of invasive candidiasis. The infection can also occur in the heart, kidney, bones, and other internal organs without being detected in the blood.

In fact, the number of cases of invasive candidiasis might be twice as high as the estimate for candidemia. Some types of Candida are increasingly resistant to the first-line and second-line antifungal medications, such as fluconazole and the echinocandins. About seven percent of all Candida bloodstream isolates tested at CDC are resistant to fluconazole.

A serendipitous finding to kick things off

Like many scientific breakthroughs, this research began with a serendipitous finding. While studying yeast infections, Prof. Steffen Jung and colleagues -- postdoctoral fellow Dr. Jarmila Sekeresova Kralova and research student Catalina Donic in Jung’s lab in Weizmann’s immunology and regenerative biology department.

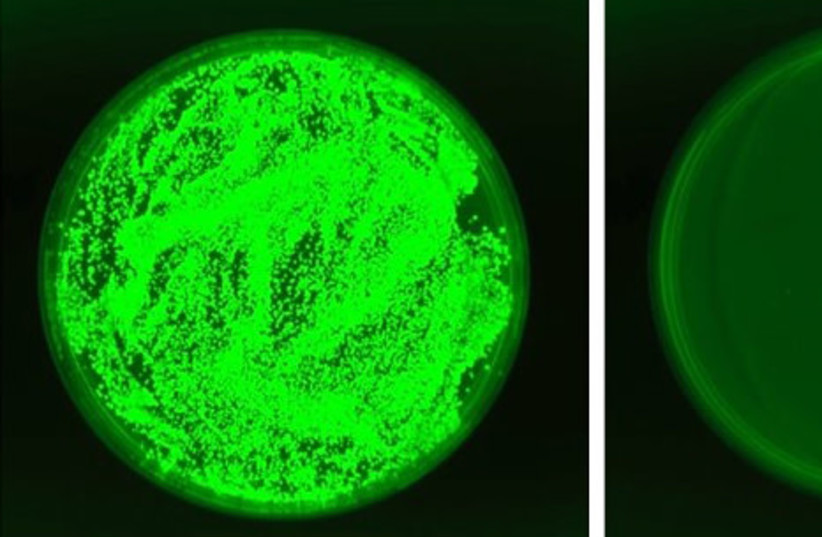

Like many scientific breakthroughs, this research began with a serendipitous finding. While studying yeast infections, Prof. Steffen Jung and colleagues at the Weizmann Institute noticed that some of their laboratory mice could not be colonized with C. albicans, but rather carried a previously unknown species of yeast.

“Knowing that C. albicans can cause life-threatening disease, we decided to investigate this further,” Jung said. “And indeed, this line of research paid off – we found that the novel yeast could robustly prevent colonization with C. albicans.”

The researchers named the new species Kazachstania weizmannii in honor of Dr. Chaim Weizmann, Israel’s first president and founder of the Weizmann Institute. This species is closely related to yeast associated with sourdough production and appears to live innocuously in the intestines of mice, even when the animals are immunosuppressed.

But most importantly, the researchers found that K. weizmannii can outcompete C. albicans for its place within the gut, reducing the population of C. albicans in mouse intestines. Moreover, although C. albicans can cross the intestinal barrier and spread to other organs in immunosuppressed mice, exposure of such animals to K. weizmannii significantly delayed the onset of invasive candidiasis.

Notably, Jung and colleagues also identified K. weizmannii and other, similar species in human gut samples. Their preliminary data suggest that the presence of K. weizmannii was mutually exclusive with the presence of Candida species, suggesting that the two species might also compete with each other in human intestines, although these findings need to be substantiated by further analyses.

“By virtue of its ability to successfully compete with C. albicans in the mouse gut, K. weizmannii reduced the presence of C. albicans and mitigated candidiasis development in immunosuppressed animals,” Jung says. “This competition between Kazachstania and Candida species might possibly have therapeutic value for the management of human diseases caused by C. albicans.”